The assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 was the immediate cause of the First World War. For four years, the great European powers fought a gruesome battle.

The entire Timeline

230 important events that occurred between 1914 and 1980 – before, during, and after Anne Frank's lifetime.

June 28, 1914Sarajevo

June 28, 1914SarajevoMurder of the Austrian Archduke: Start of the First World War

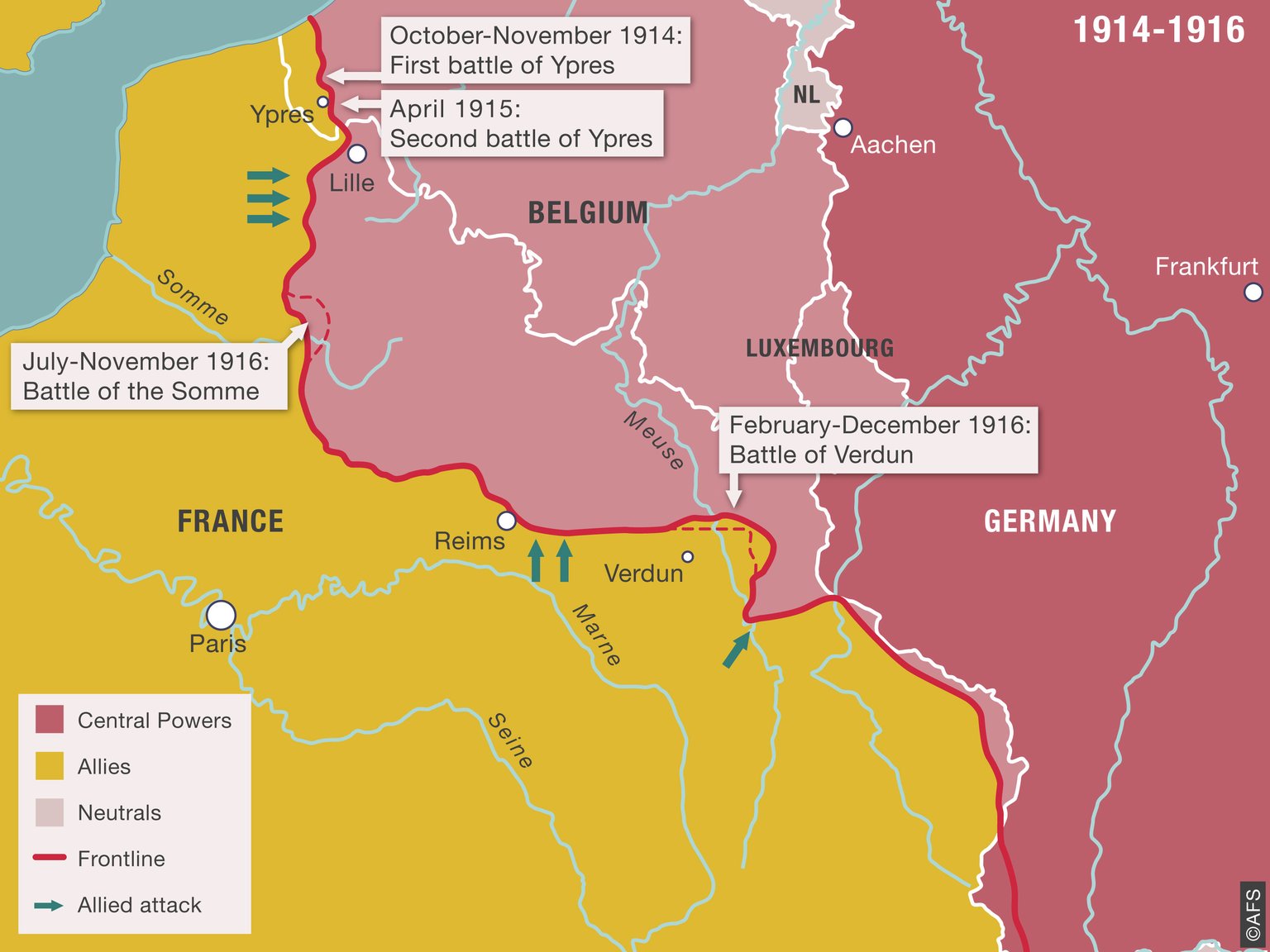

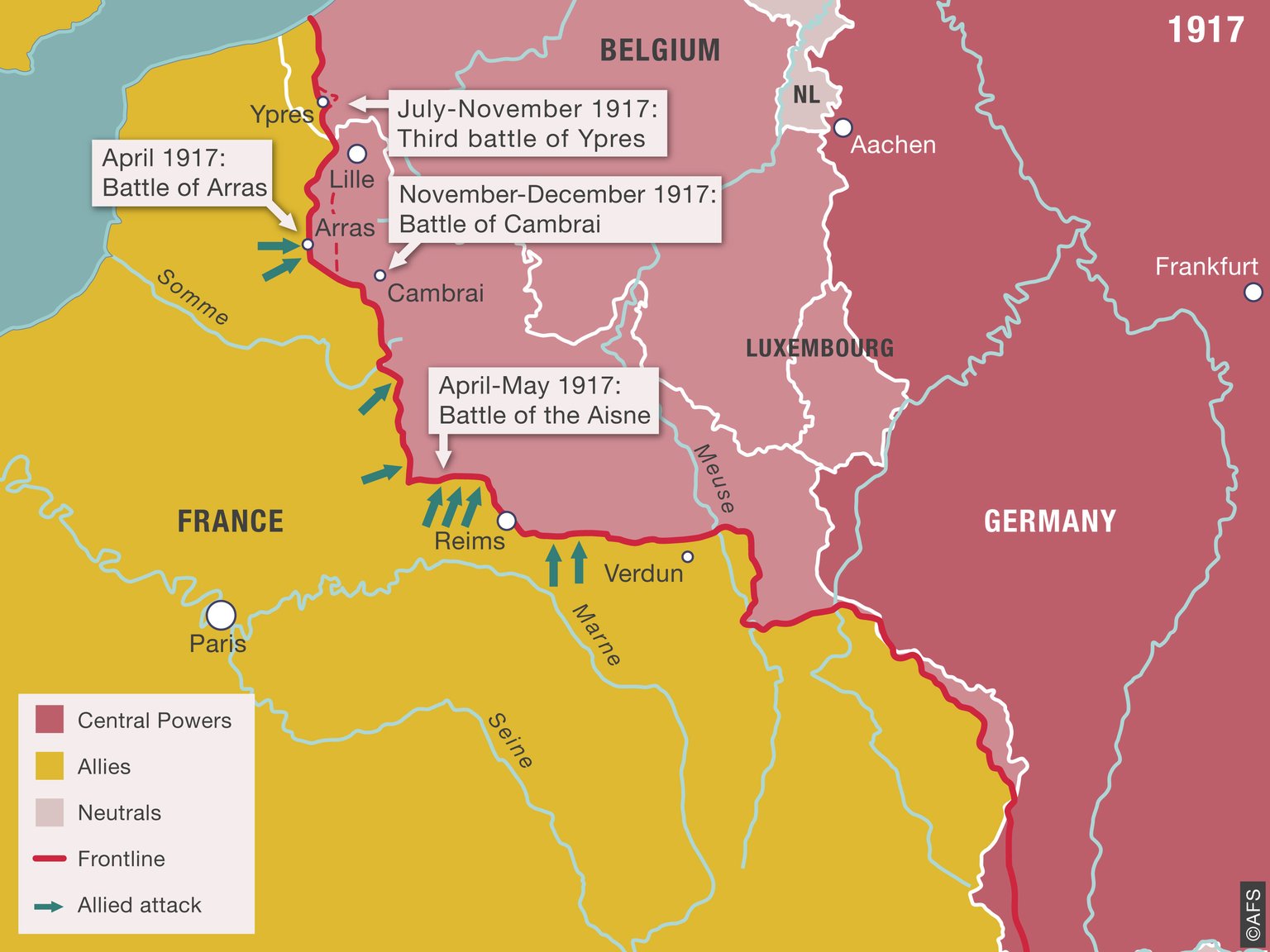

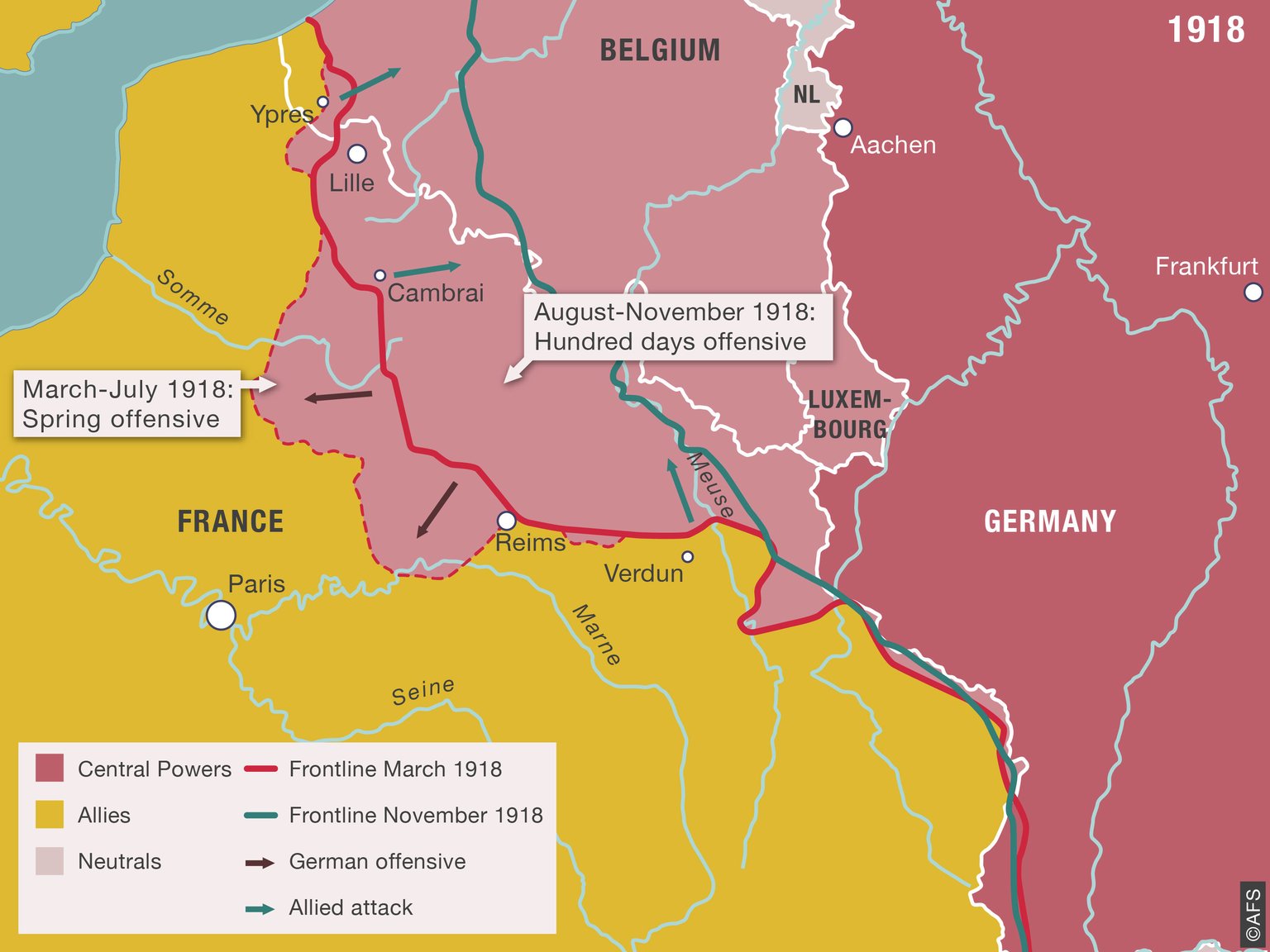

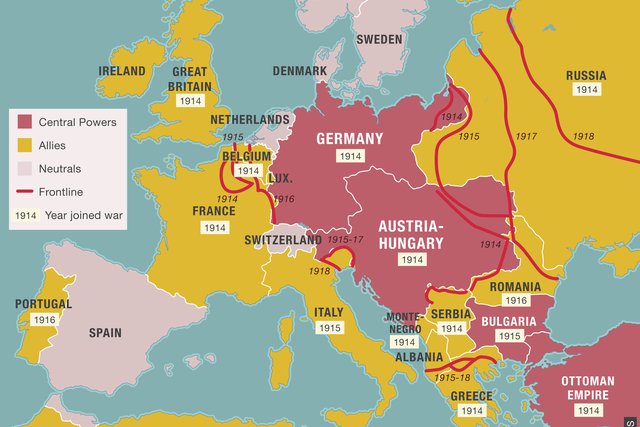

1914-1918Europe

1914-1918EuropeMaps of the First World War

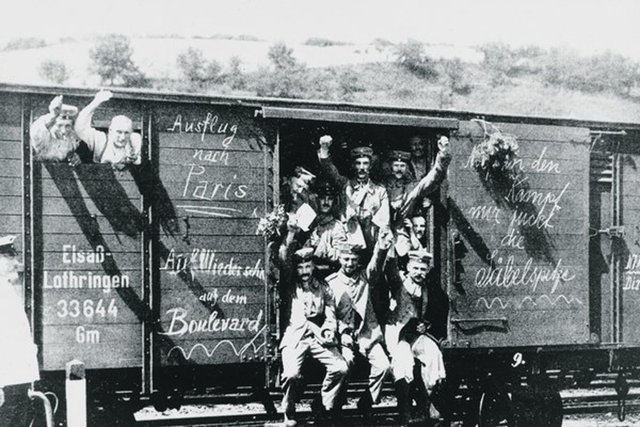

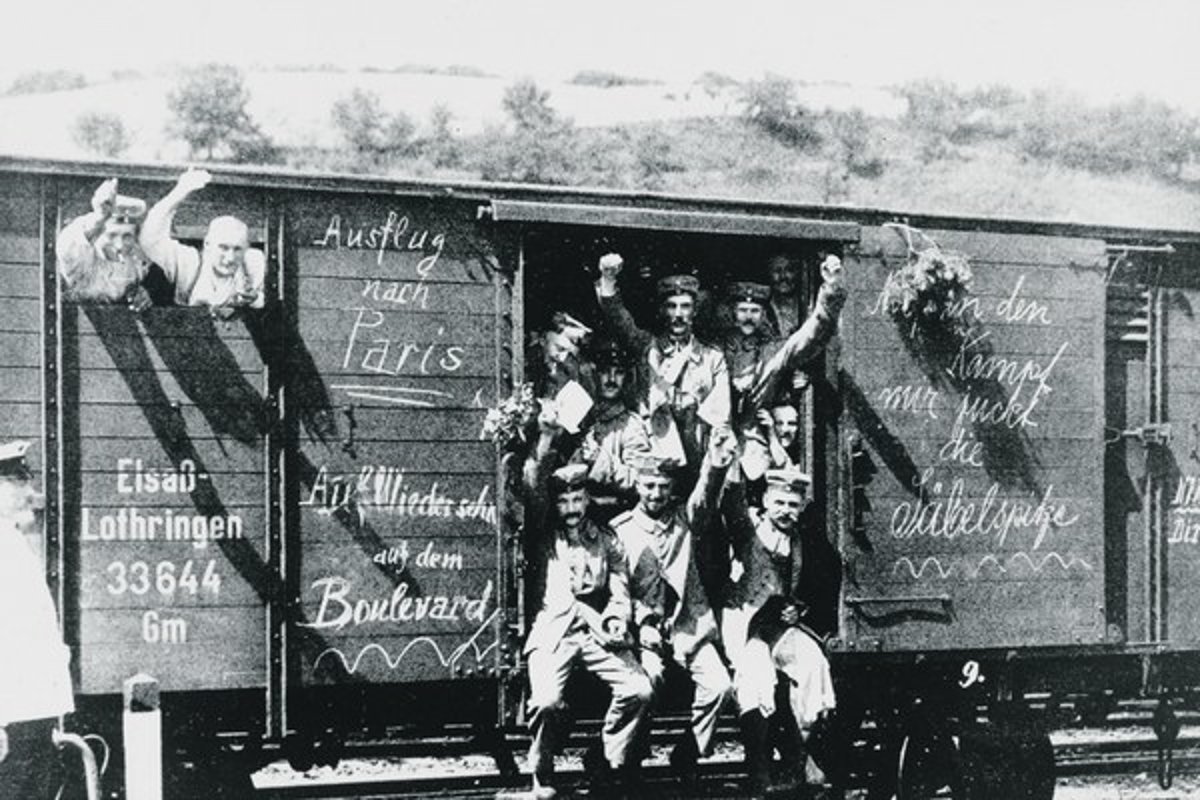

Aug. 2, 1914Europe

Aug. 2, 1914EuropeWar enthusiasm

April 22, 1915Ypres

April 22, 1915YpresThe German army uses poison gas against French troops

Aug. 6, 1915Germany

Aug. 6, 1915GermanyOtto Frank in the First World War

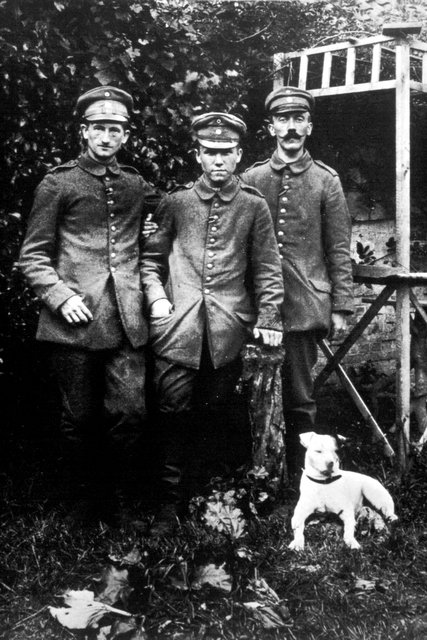

July 1, 1916France

July 1, 1916FranceHitler as a soldier in the First World War

Dec. 1, 1916Germany

Dec. 1, 1916GermanyFritz Pfeffer in military service

April 6, 1917Washington

April 6, 1917WashingtonThe United States declare war on Germany

Oct. 5, 1917Ypres

Oct. 5, 1917YpresRuins after the Battle of Passchendaele

Nov. 7, 1917Petrograd (Saint Petersburg)

Nov. 7, 1917Petrograd (Saint Petersburg)The Russian Revolution: Armistice with Germany

1917-1919Berlin

1917-1919BerlinFamine in Germany

Nov. 9, 1918Germany

Nov. 9, 1918GermanyNovember Revolution: Germany becomes a republic

Nov. 10, 1918Eijsden, Netherlands

Nov. 10, 1918Eijsden, NetherlandsThe German emperor flees to the Netherlands

Nov. 11, 1918Compiègne

Nov. 11, 1918CompiègneGermany agrees on an armistice with the United Kingdom and France

Nov. 30, 1918Aachen

Nov. 30, 1918AachenThe Belgian army occupies Aachen

May 15, 1919Berlin

May 15, 1919BerlinGermany loses the war: Protests against the Treaty of Versailles

1919Europe

1919EuropeAltered frontiers in Europe

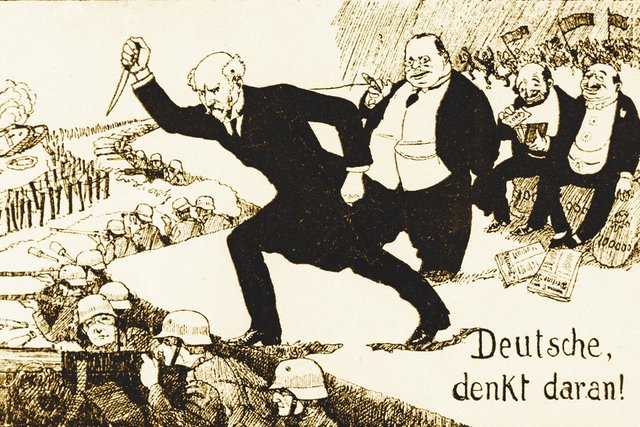

Nov. 18, 1919Berlin

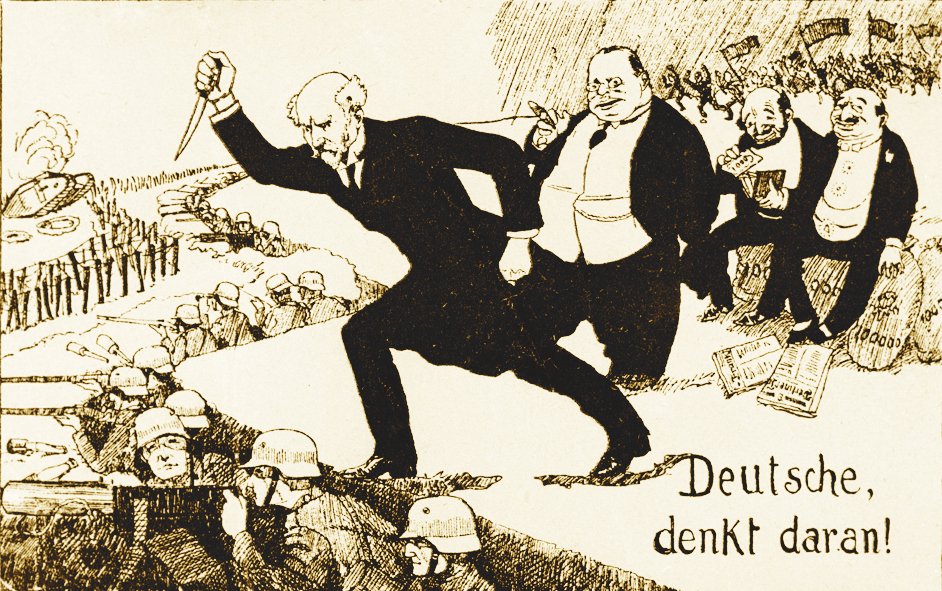

Nov. 18, 1919BerlinThe stab-in-the-back myth

March 13, 1920Germany

March 13, 1920GermanyFailed coup in Germany

Dec. 1, 1920Vienna

Dec. 1, 1920ViennaPoverty and hunger in Vienna: Miep Gies comes to the Netherlands

Jan. 1, 1923Amsterdam

Jan. 1, 1923AmsterdamOtto’s first time in Amsterdam

1923Berlin

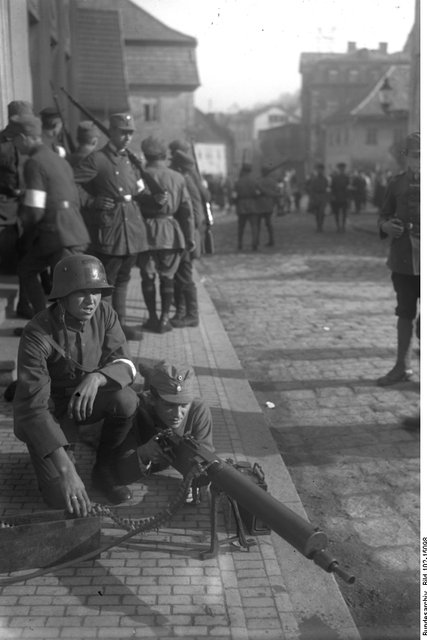

1923BerlinPolice officers guard a bakery in Berlin

Nov. 8, 1923Munich

Nov. 8, 1923MunichAdolf Hitler commits a coup and fails

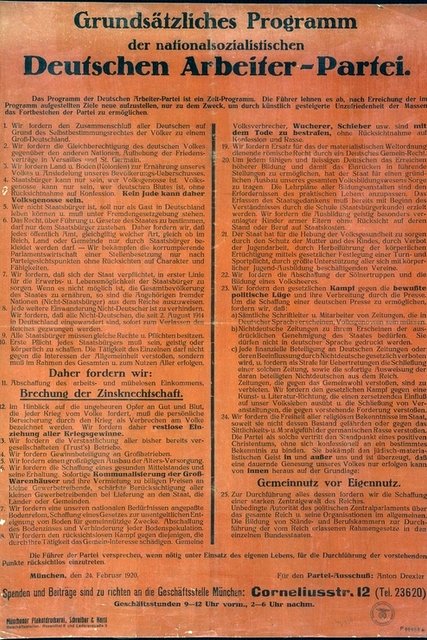

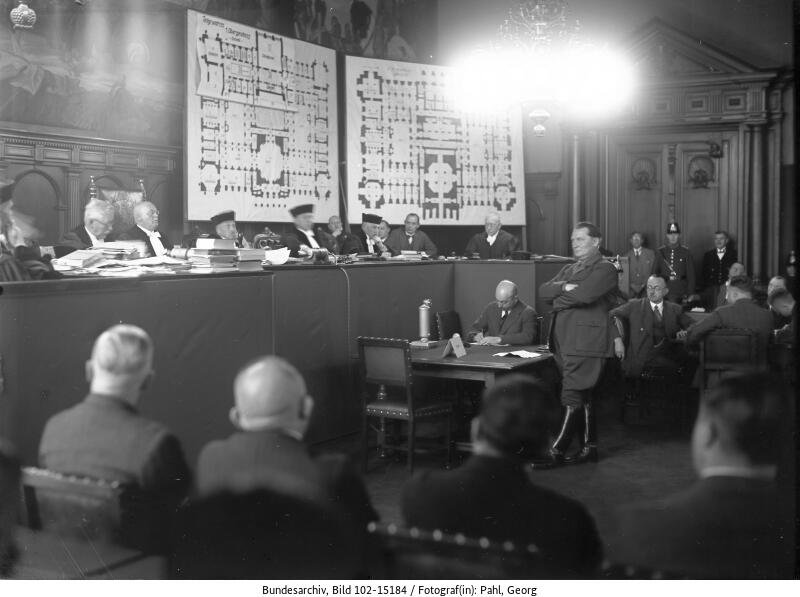

Feb. 24, 1924Munich

Feb. 24, 1924MunichThe NSDAP party programme

May 12, 1925Aachen

May 12, 1925AachenOtto Frank and Edith Holländer get married

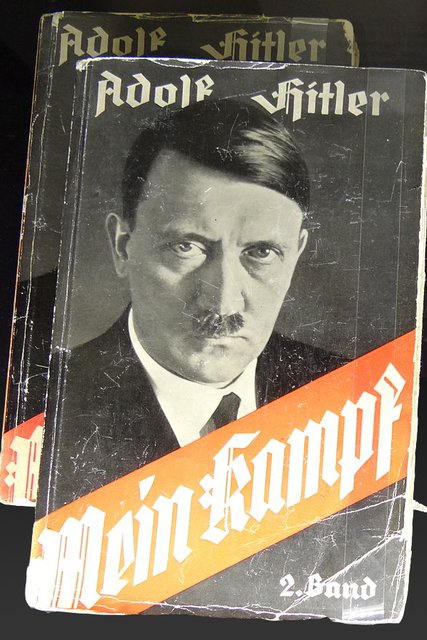

July 18, 1925Munich

July 18, 1925MunichAdolf Hitler publishes ‘Mein Kampf’

Feb. 16, 1926Frankfurt

Feb. 16, 1926FrankfurtMargot Frank is born

Aug. 1, 1927Nuremberg

Aug. 1, 1927NurembergNazis organise a party convention in Nuremberg

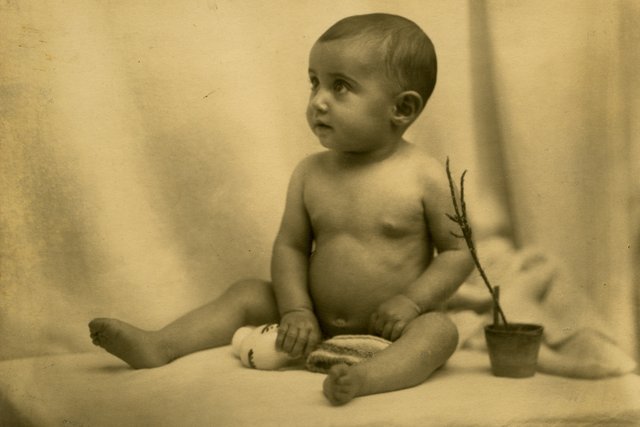

June 12, 1929Frankfurt

June 12, 1929FrankfurtAnne Frank is born

July 13, 1931Berlin

July 13, 1931BerlinSavers storm a Berlin bank

March 1, 1932Berlin

March 1, 1932BerlinThe Iron Front marches against the Nazis

Sept. 1, 1932Berlin

Sept. 1, 1932BerlinRent strike in Berlin

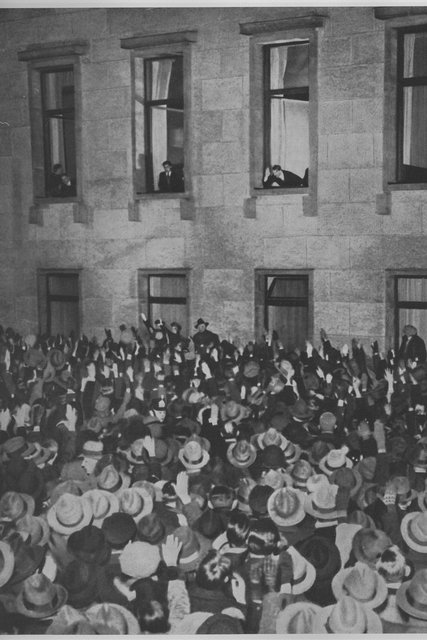

Jan. 30, 1933Berlin

Jan. 30, 1933BerlinHitler and the Nazis come to power in Germany

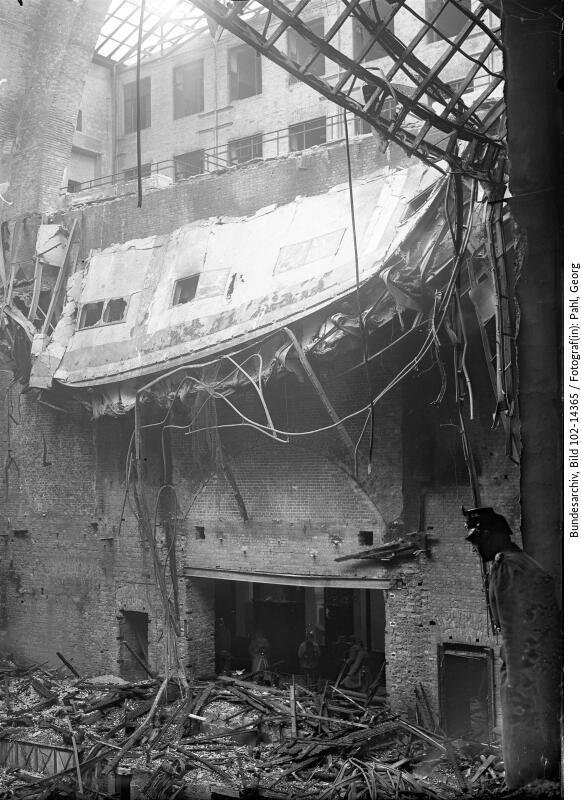

Feb. 27, 1933Berlin

Feb. 27, 1933BerlinReichstag fire

March 10, 1933Frankfurt

March 10, 1933FrankfurtThe last months in Frankfurt

March 13, 1933Frankfurt

March 13, 1933FrankfurtIn Frankfurt, the NSDAP comes to power

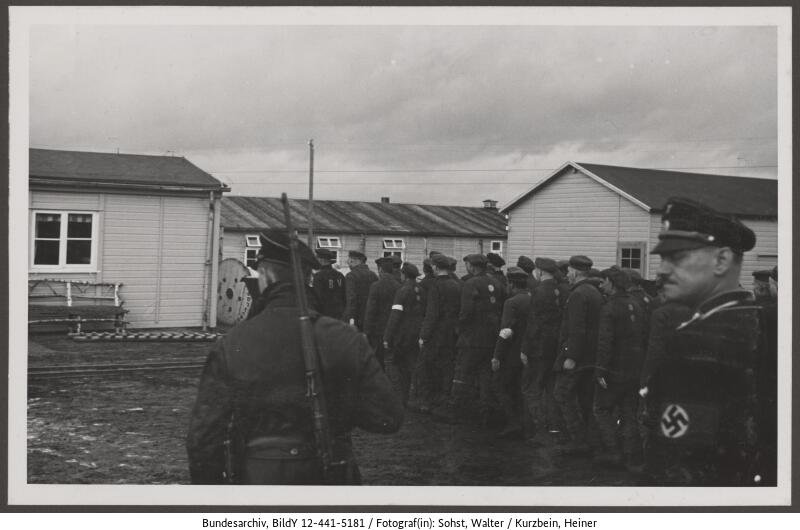

March 22, 1933Dachau

March 22, 1933DachauThe construction of Dachau: The first concentration camp

March 23, 1933Berlin

March 23, 1933BerlinThe Enabling Act: even more power for Hitler

April 1, 1933Germany

April 1, 1933GermanyBoycott of Jewish shops

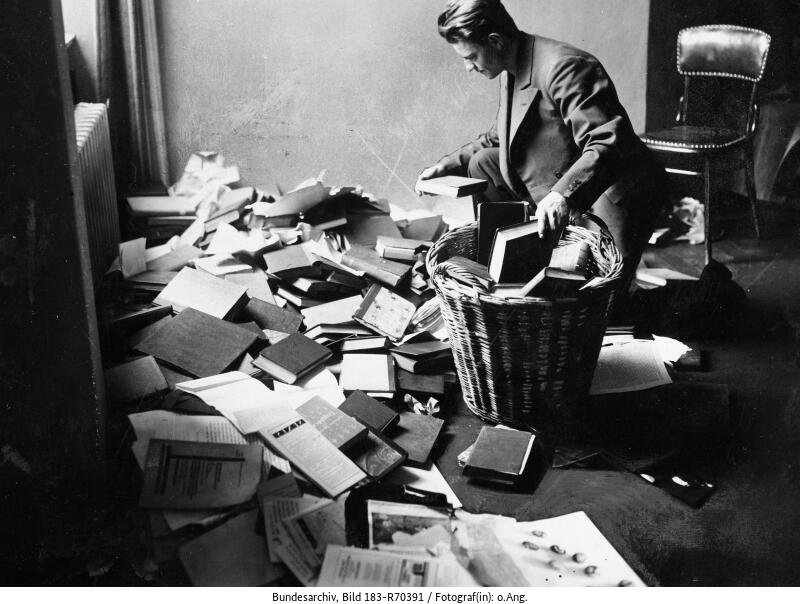

May 10, 1933Germany

May 10, 1933GermanyBook burning at German universities

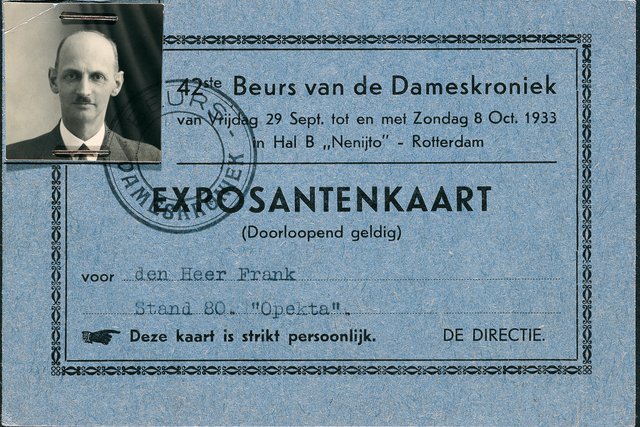

July 4, 1933The Netherlands

July 4, 1933The NetherlandsOtto starts Opekta in the Netherlands

Sept. 13, 1933Brandenburg, Germany

Sept. 13, 1933Brandenburg, GermanyFactory workers practise wearing gas masks

Sept. 23, 1933Frankfurt

Sept. 23, 1933FrankfurtThe Nazis start building motorways

Dec. 1, 1933Germany

Dec. 1, 1933GermanyGermany is a one-party state

Feb. 16, 1934Amsterdam

Feb. 16, 1934AmsterdamAnne Frank emigrates to Amsterdam: a new life in a new city

April 9, 1934Amsterdam

April 9, 1934AmsterdamAnne Frank in kindergarten

Aug. 15, 1935Berlin

Aug. 15, 1935BerlinJulius Streicher’s speech at the Berlin Sportpalast

Sept. 15, 1935Nuremberg

Sept. 15, 1935NurembergThe Nuremberg Race Laws

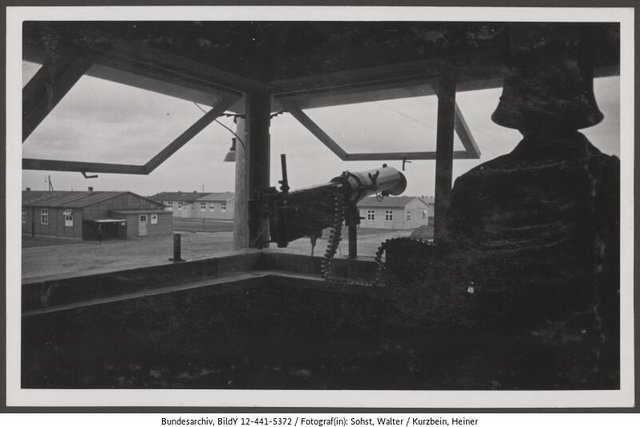

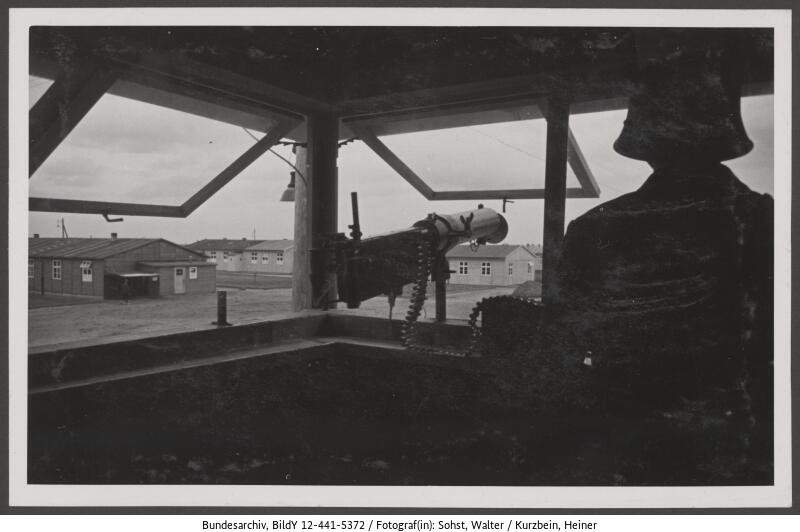

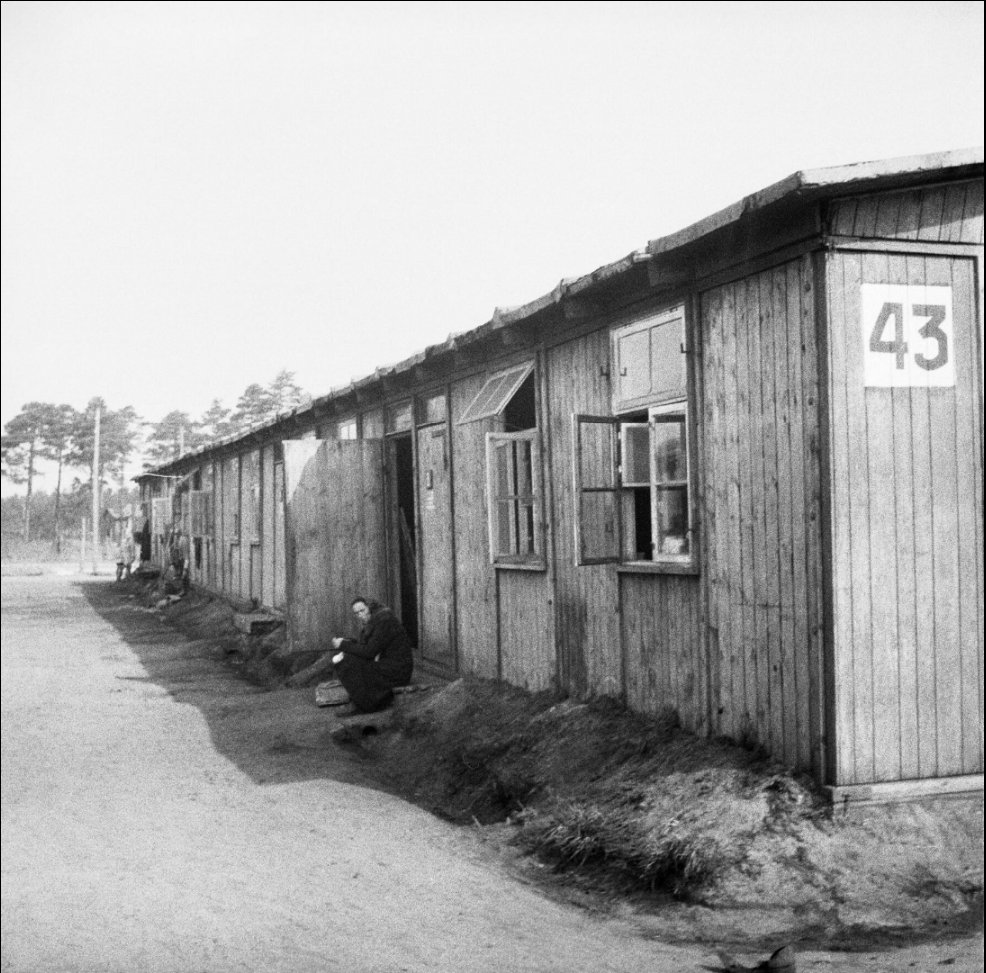

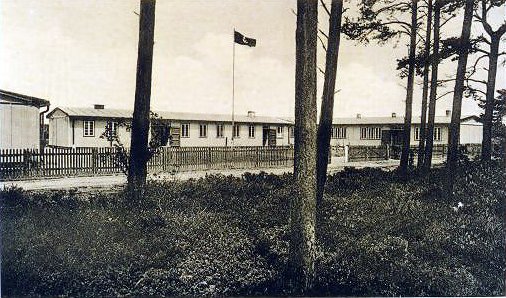

December 1935Bergen-Belsen

December 1935Bergen-BelsenMilitary training grounds near Bergen-Belsen

March 7, 1936Germany

March 7, 1936GermanyHitler’s first military action: German troops occupy the Rhineland

1936-1939Europe

1936-1939EuropeThe expansion of Germany

Oct. 25, 1936Berlin

Oct. 25, 1936BerlinNazi Germany and fascist Italy become friends

April 26, 1937Guernica

April 26, 1937GuernicaThe German Luftwaffe bombs Guernica

June 6, 1937Amsterdam

June 6, 1937AmsterdamConsecration of the Liberal Jewish Synagogue in Amsterdam

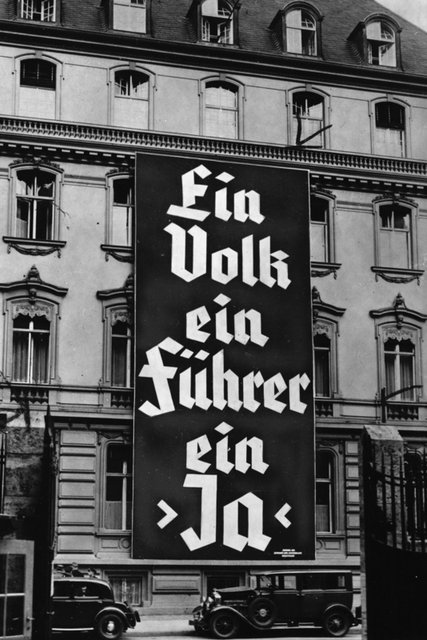

March 15, 1938Vienna

March 15, 1938ViennaThe Anschluss: Germany occupies Austria

March 18, 1938Vienna

March 18, 1938ViennaEichmann invades the Jewish Congregation in Vienna

July 6, 1938Évian-les-Bains

July 6, 1938Évian-les-BainsÉvian Conference: no room for Jewish refugees

Sept. 30, 1938Munich

Sept. 30, 1938MunichThe Munich Agreement

Oct. 27, 1938Germany

Oct. 27, 1938GermanyThe Gestapo deports Polish Jews to Poland

Nov. 9, 1938Germany

Nov. 9, 1938GermanyThe Kristallnacht proves that Jews have no future in Germany

December 1938Amsterdam

December 1938AmsterdamJewish refugees in Amsterdam

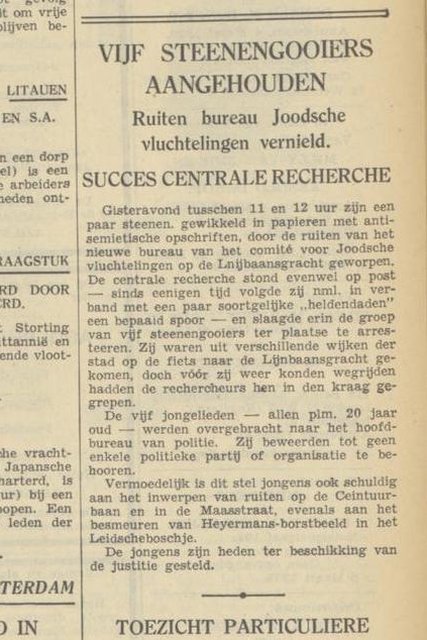

Dec. 9, 1938Amsterdam

Dec. 9, 1938AmsterdamFritz Pfeffer flees Germany for the Netherlands

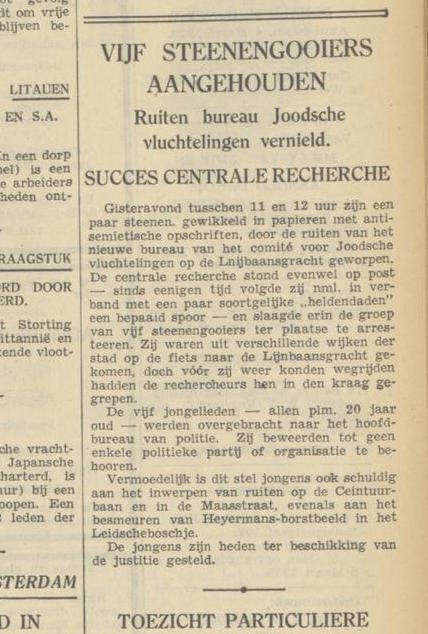

March 4, 1939Amsterdam

March 4, 1939AmsterdamAntisemitic youth caught in the act of vandalism

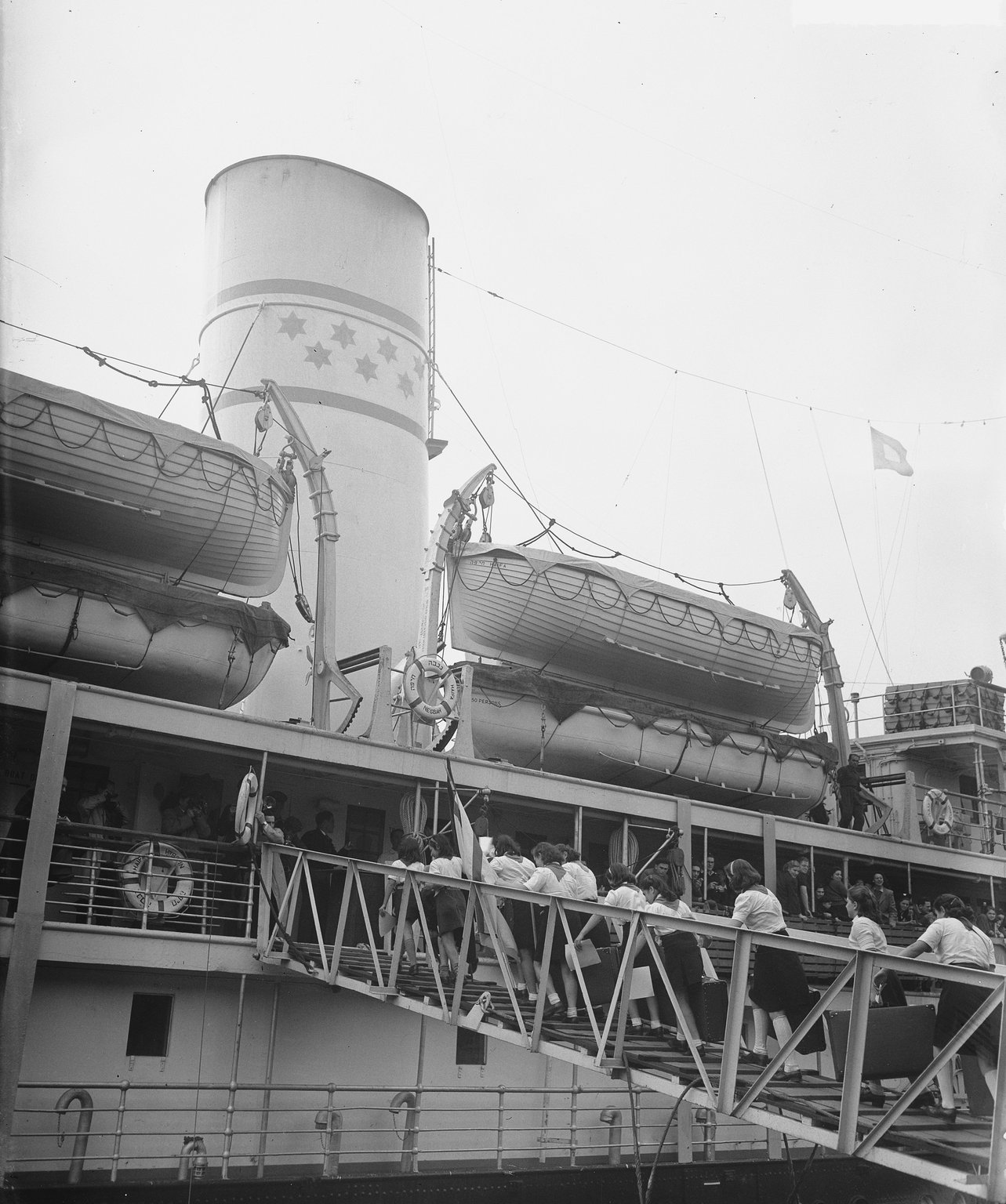

May 27, 1939Havana

May 27, 1939HavanaRefugee ship refused access

August 1939Berlin

August 1939BerlinMurder of the disabled

August 1939Westerbork

August 1939WesterborkShelter for refugees: A camp near Westerbork

Aug. 23, 1939Moscow

Aug. 23, 1939MoscowGermany and the Soviet Union sign a non-aggression pact

Aug. 28, 1939Amsterdam

Aug. 28, 1939AmsterdamAmsterdam prepares for war

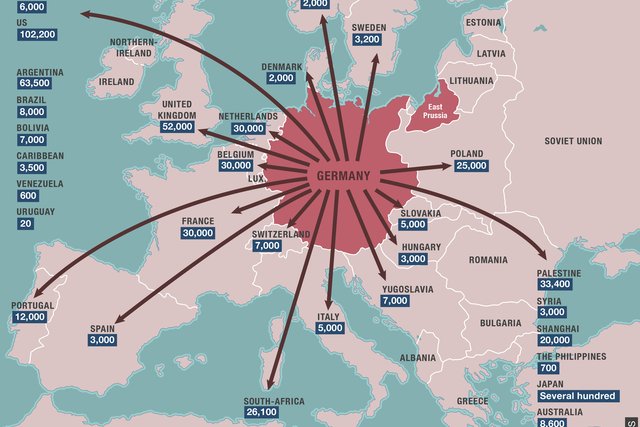

1933-1939Germany

1933-1939GermanyJewish refugees from Nazi Germany

Sept. 1, 1939Poland

Sept. 1, 1939PolandThe start of the Second World War: Germany invades Poland

Oct. 1, 1939Occupied Poland

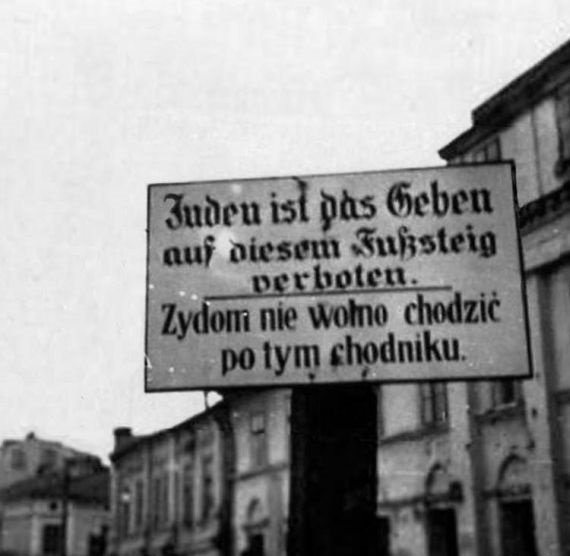

Oct. 1, 1939Occupied PolandJews are humiliated in occupied Poland

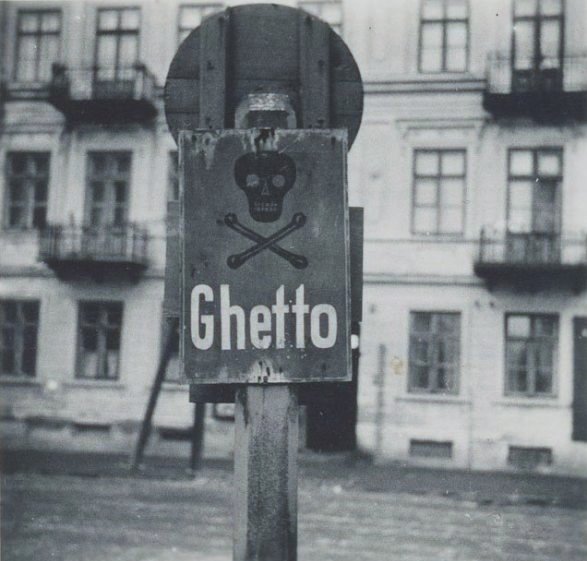

Oct. 8, 1939Piotrków Trybunalski

Oct. 8, 1939Piotrków TrybunalskiGhettos in occupied Poland

April 9, 1940Denmark - Norway

April 9, 1940Denmark - NorwayGermany invades Denmark and Norway

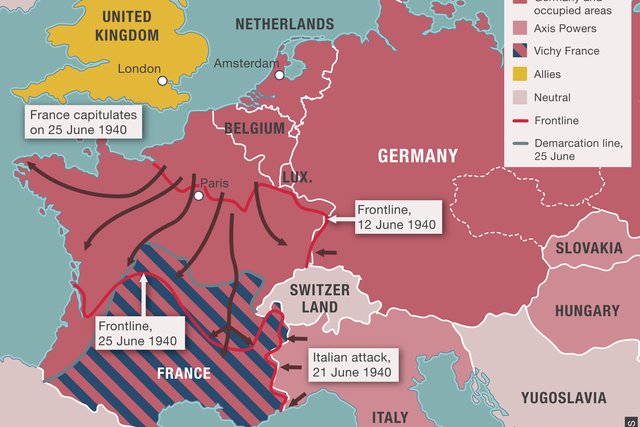

May 10, 1940Western Europe

May 10, 1940Western EuropeGermany invades the Netherlands, Belgium, and France

May 11, 1940Rhenen

May 11, 1940RhenenBattle of the Grebbeberg

May 13, 1940Hoek van Holland

May 13, 1940Hoek van HollandQueen Wilhelmina escapes to England

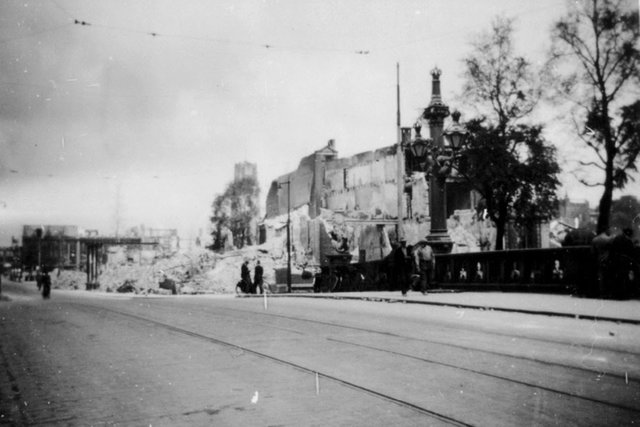

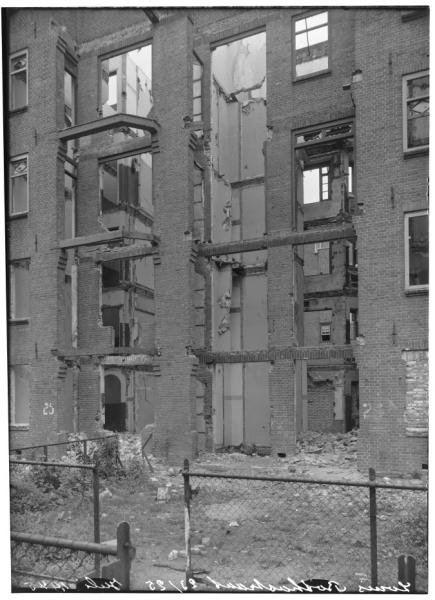

May 14, 1940Rotterdam

May 14, 1940RotterdamGermany bombs Rotterdam. The Netherlands surrenders

May 14, 1940IJmuiden

May 14, 1940IJmuidenJewish children taken to England at the last minute

May 15, 1940Amsterdam

May 15, 1940AmsterdamThe German army enters Amsterdam

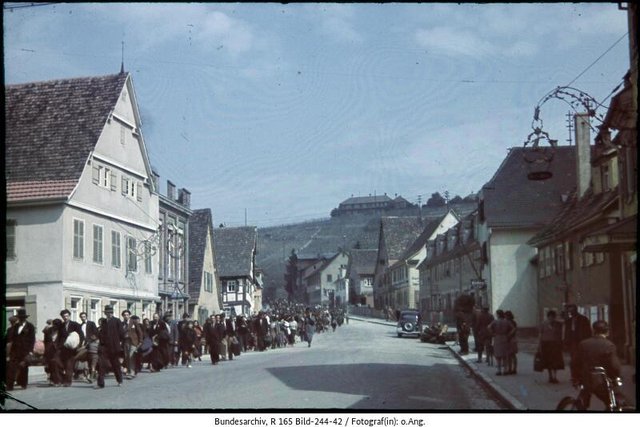

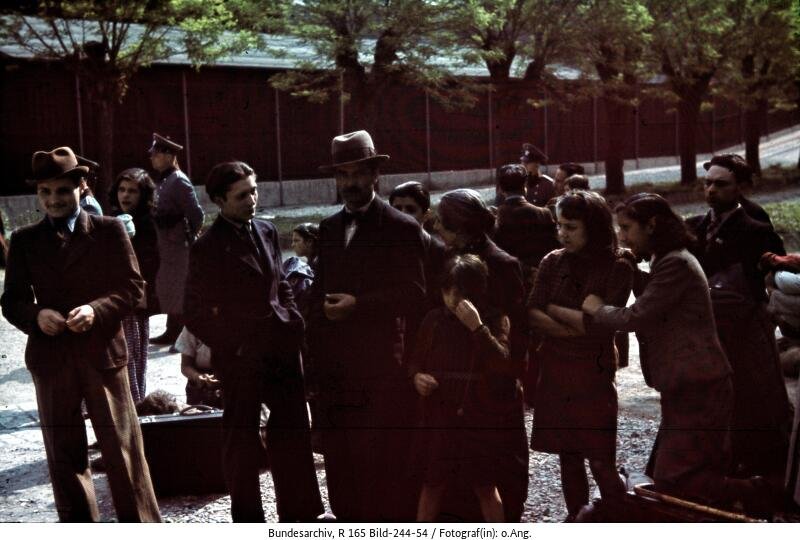

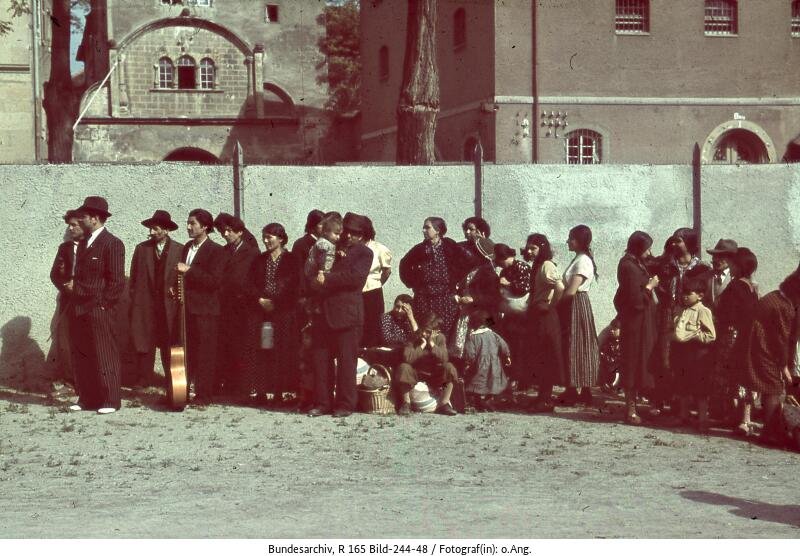

May 22, 1940Asperg, Germany

May 22, 1940Asperg, GermanyRoma and Sinti are deported from Germany

May 29, 1940The Hague

May 29, 1940The HagueThe Nazis assume power in the Netherlands

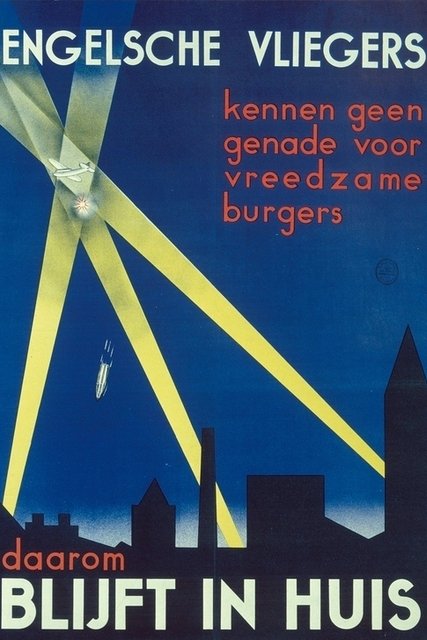

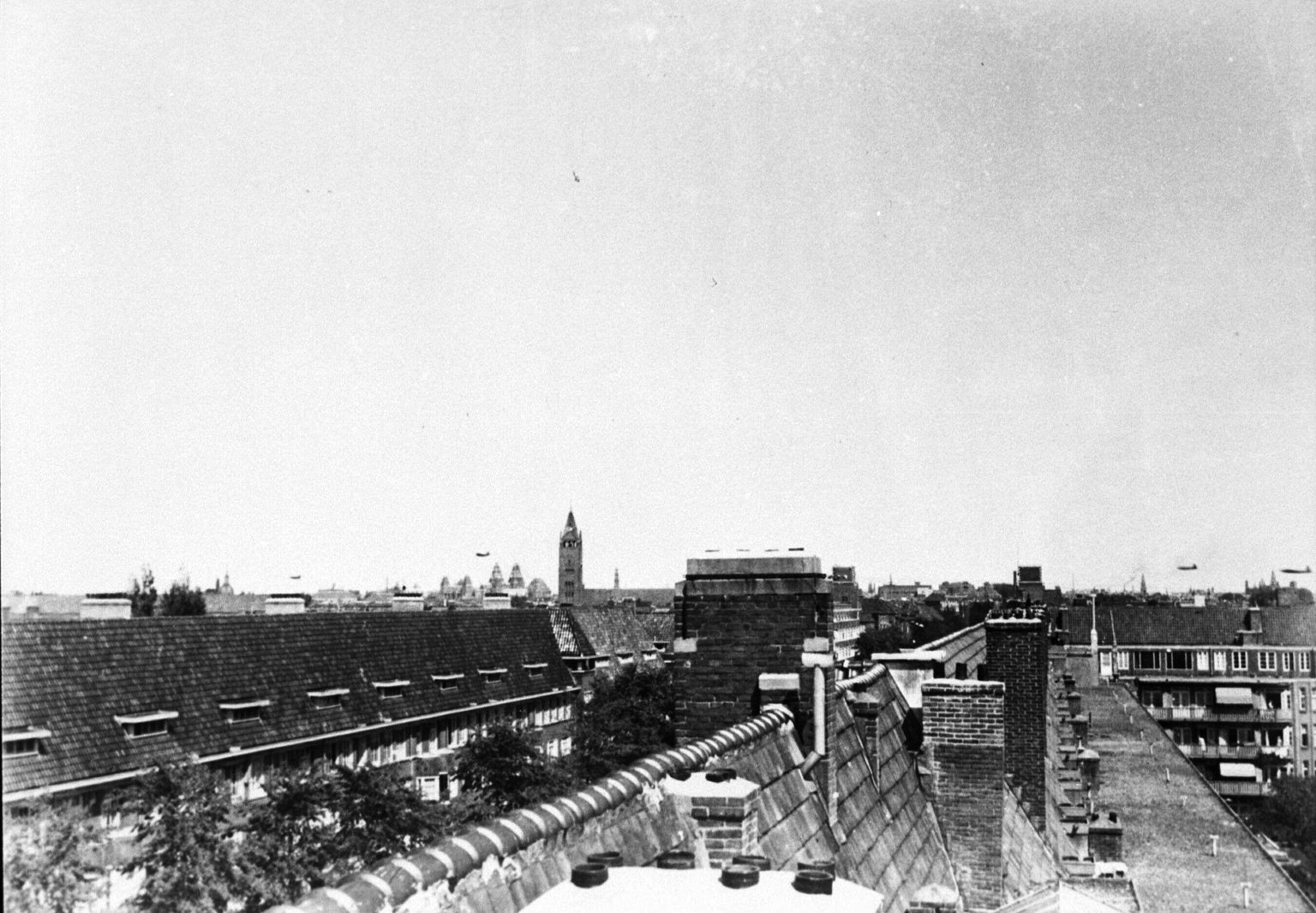

1940 - 1945Amsterdam

1940 - 1945AmsterdamThe Netherlands in the dark

1940Europe

1940EuropeGermany occupies Europe

June 23, 1940Paris

June 23, 1940ParisAdolf Hitler in Paris

1940 - 1941Great Britain

1940 - 1941Great BritainThe Battle of Britain

July 18, 1940Berlin

July 18, 1940BerlinRejoicing in Berlin

Aug. 5, 1940Amsterdam

Aug. 5, 1940AmsterdamRitual slaughter is prohibited

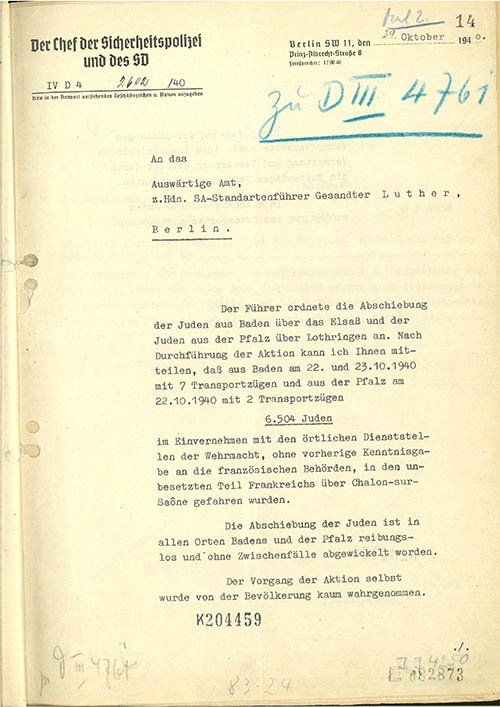

Oct. 22, 1940Baden, Germany

Oct. 22, 1940Baden, GermanyJews are deported from southwestern Germany

Nov. 21, 1940The Netherlands

Nov. 21, 1940The NetherlandsJewish civil servants are dismissed

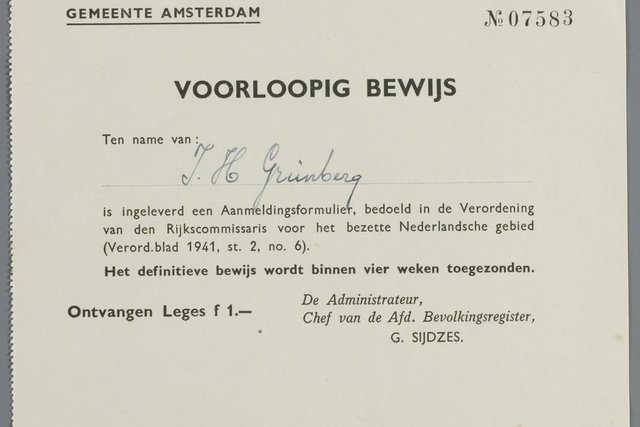

Jan. 7, 1941The Netherlands

Jan. 7, 1941The NetherlandsCinemas are off limits to Jews

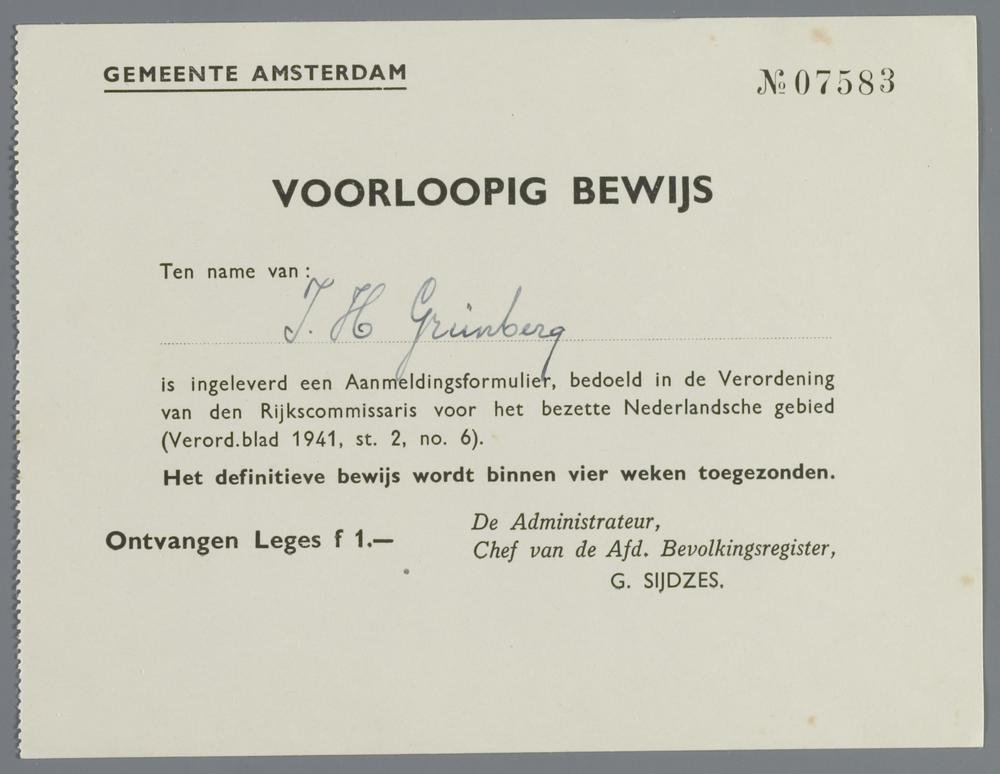

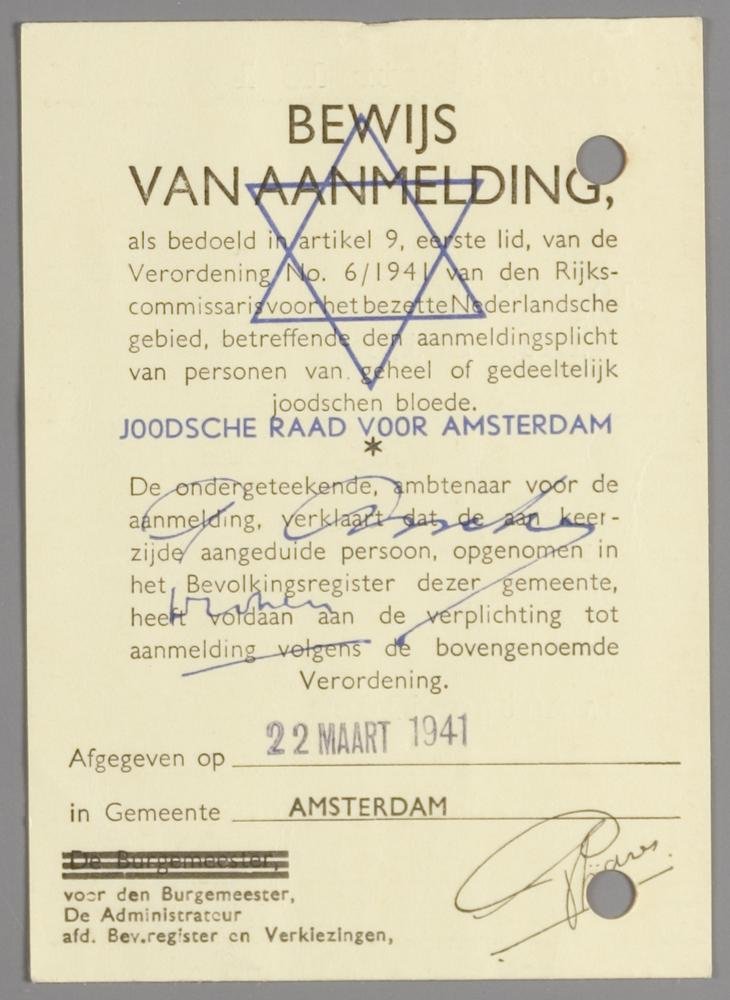

Feb. 3, 1941The Netherlands

Feb. 3, 1941The NetherlandsAll Jews need to register

Feb. 9, 1941Amsterdam

Feb. 9, 1941AmsterdamCafé Alcazar is destroyed

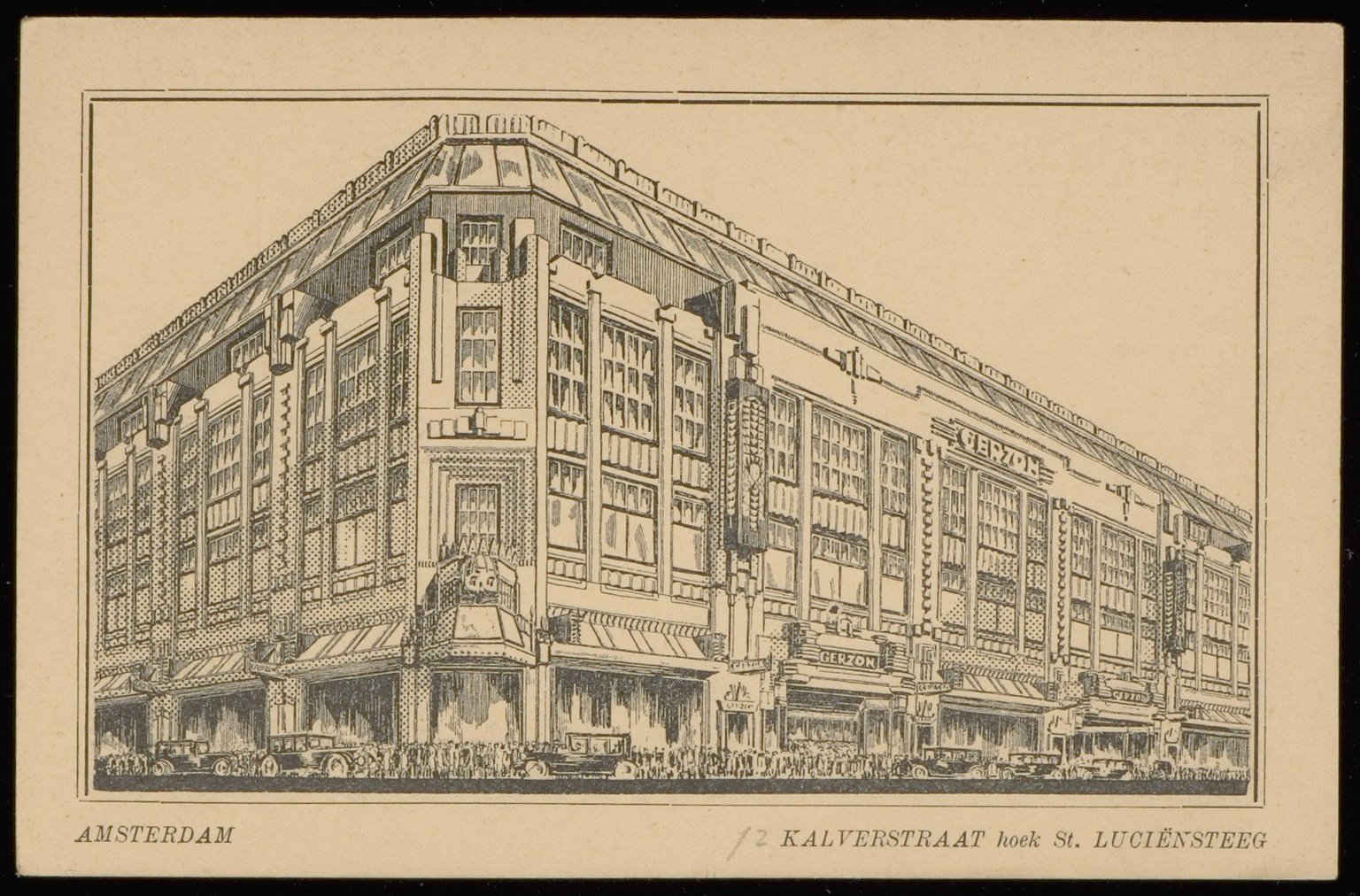

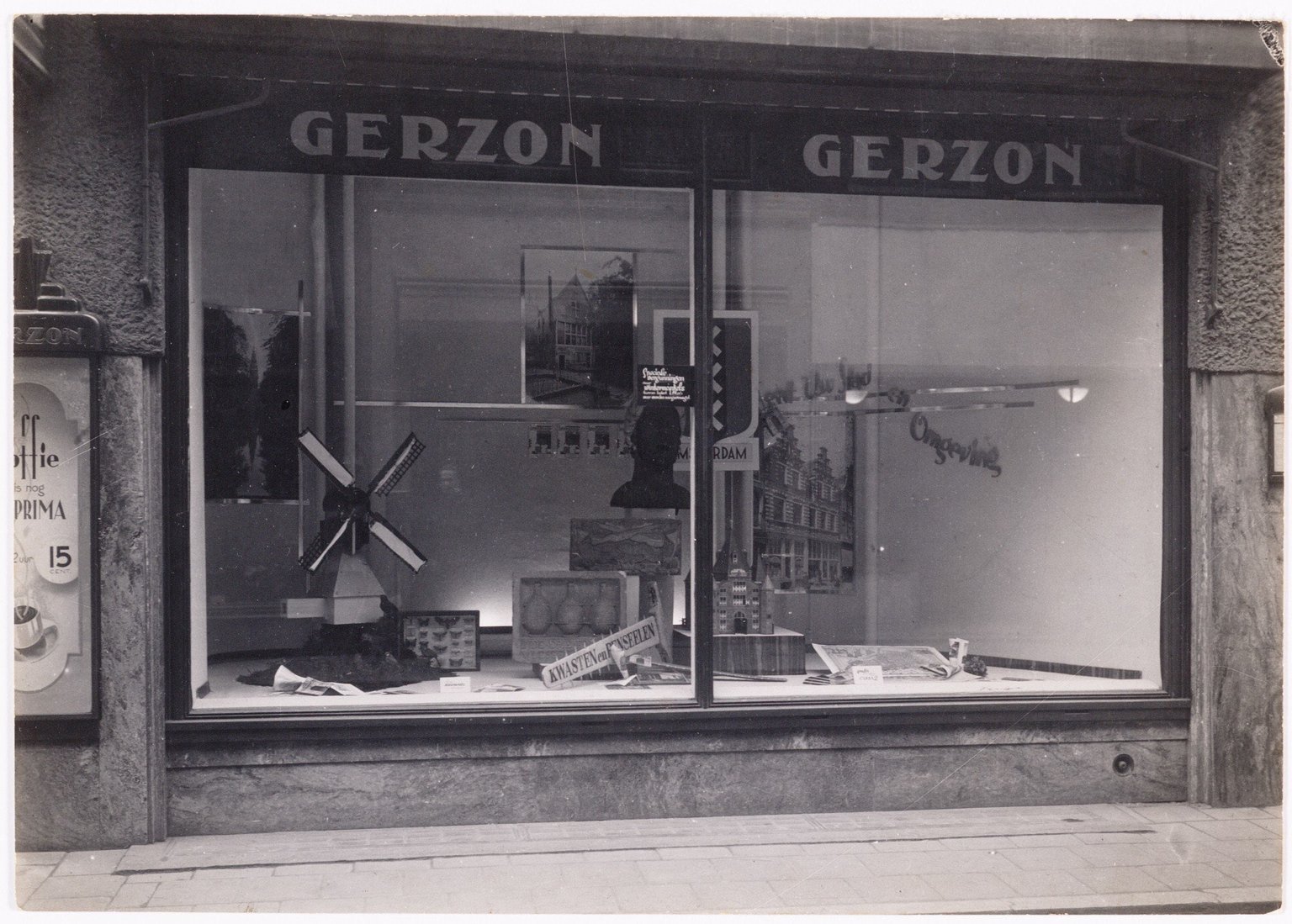

Feb. 12, 1941Amsterdam

Feb. 12, 1941AmsterdamAryanisation of Gerzon house of fashion

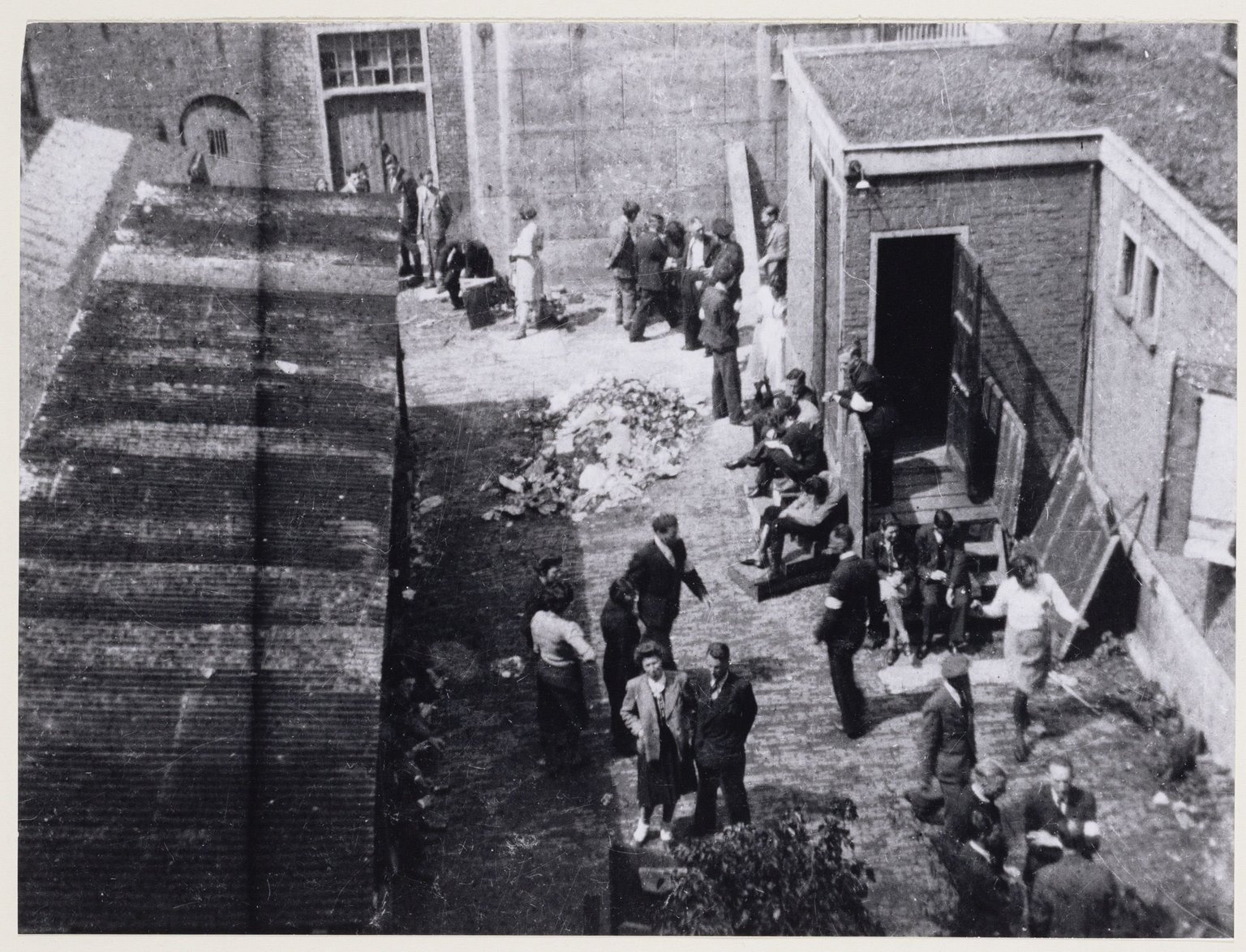

22 and 23 February, 1941Amsterdam

22 and 23 February, 1941AmsterdamMass raids in Amsterdam: The first deportations of Dutch Jews

25 and 26 February, 1941Amsterdam

25 and 26 February, 1941AmsterdamThe February Strike

March 12, 1941Amsterdam

March 12, 1941AmsterdamSeyss-Inquart warns the Dutch Jews

April 1, 1941The Netherlands

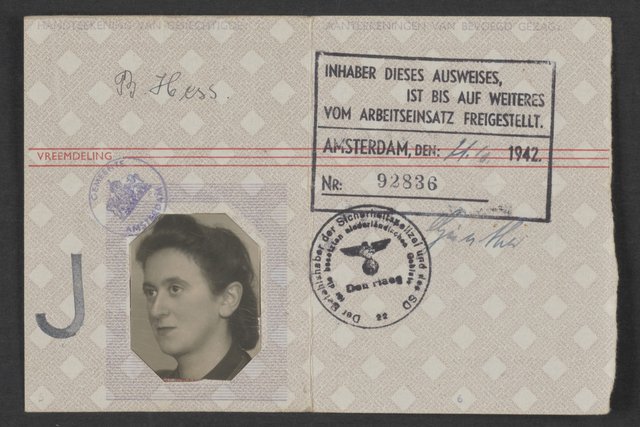

April 1, 1941The NetherlandsThe Dutch government makes carrying an identity card compulsory

April 6, 1941Yugoslavia - Greece

April 6, 1941Yugoslavia - GreeceGermany and its allies invade Greece and Yugoslavia

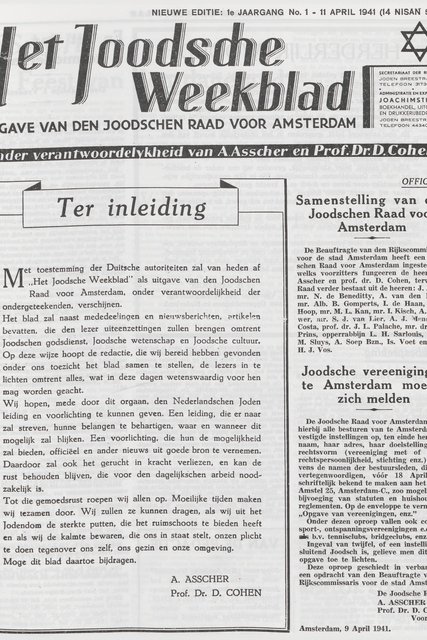

April 11, 1941Amsterdam

April 11, 1941AmsterdamThe Jewish Council publishes Het Joodsche Weekblad

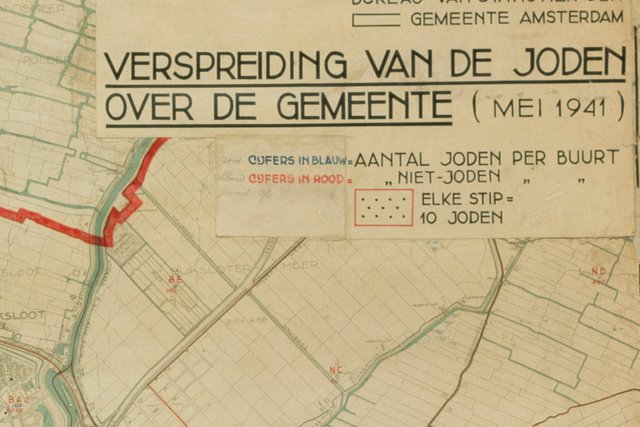

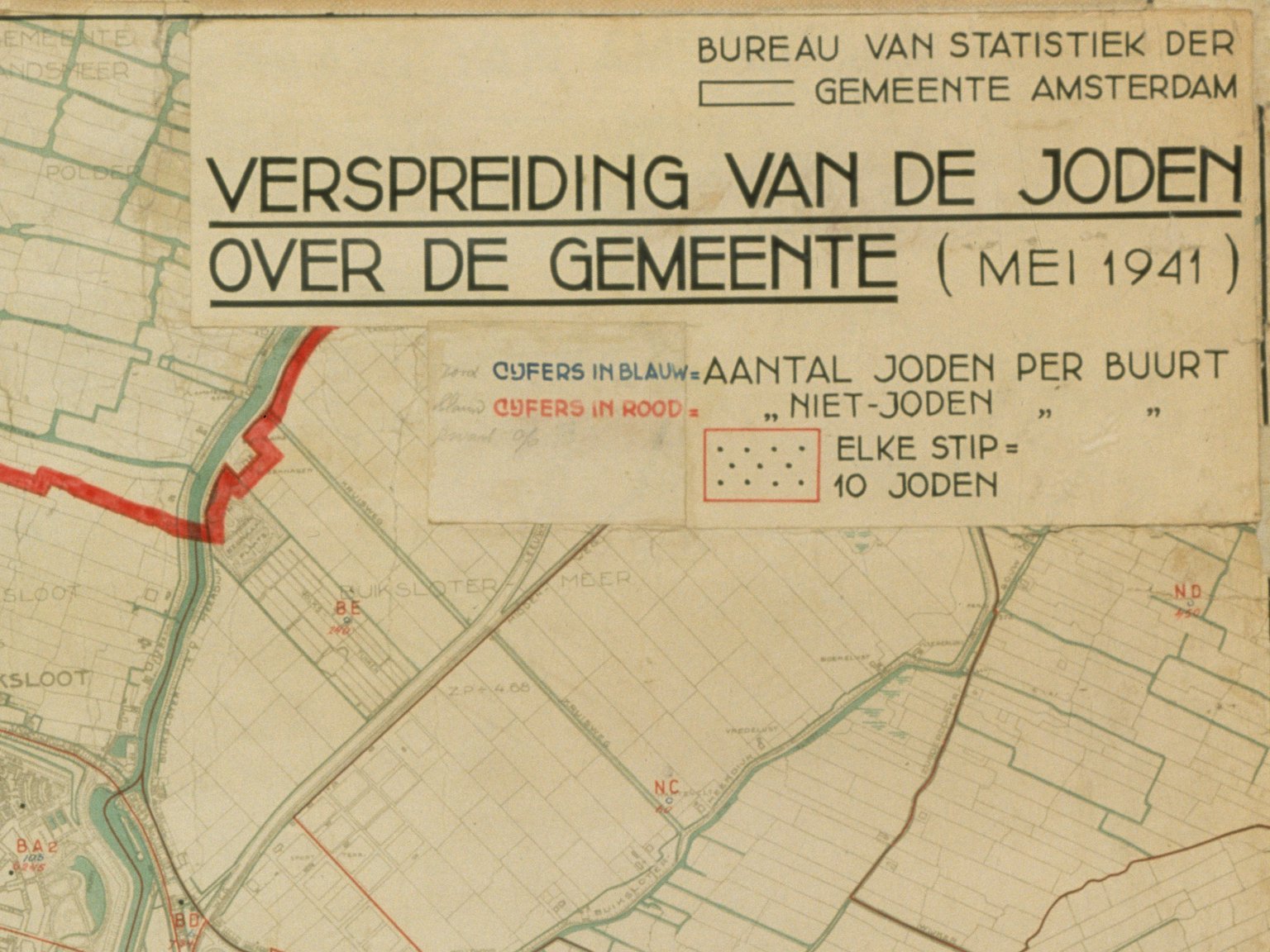

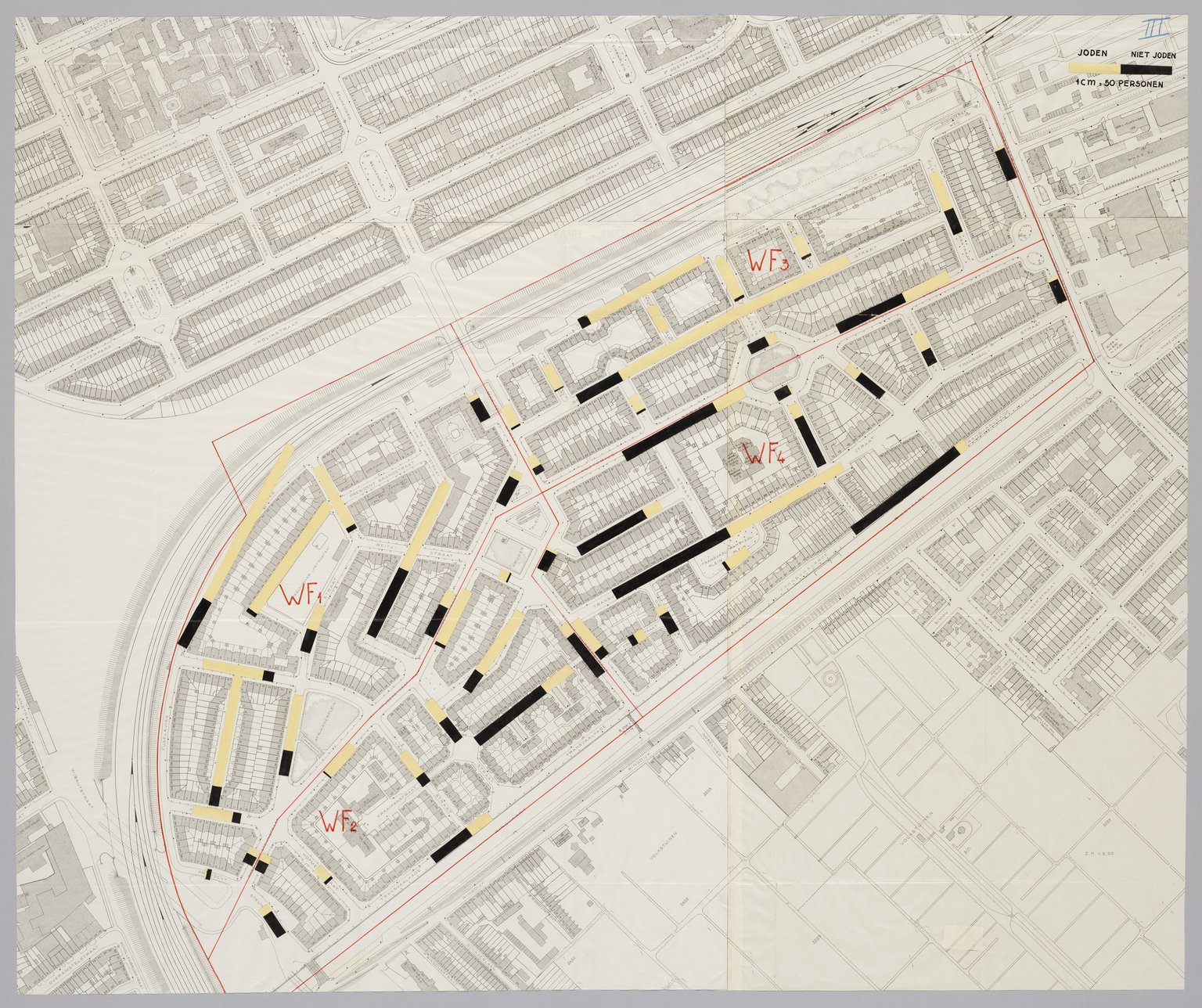

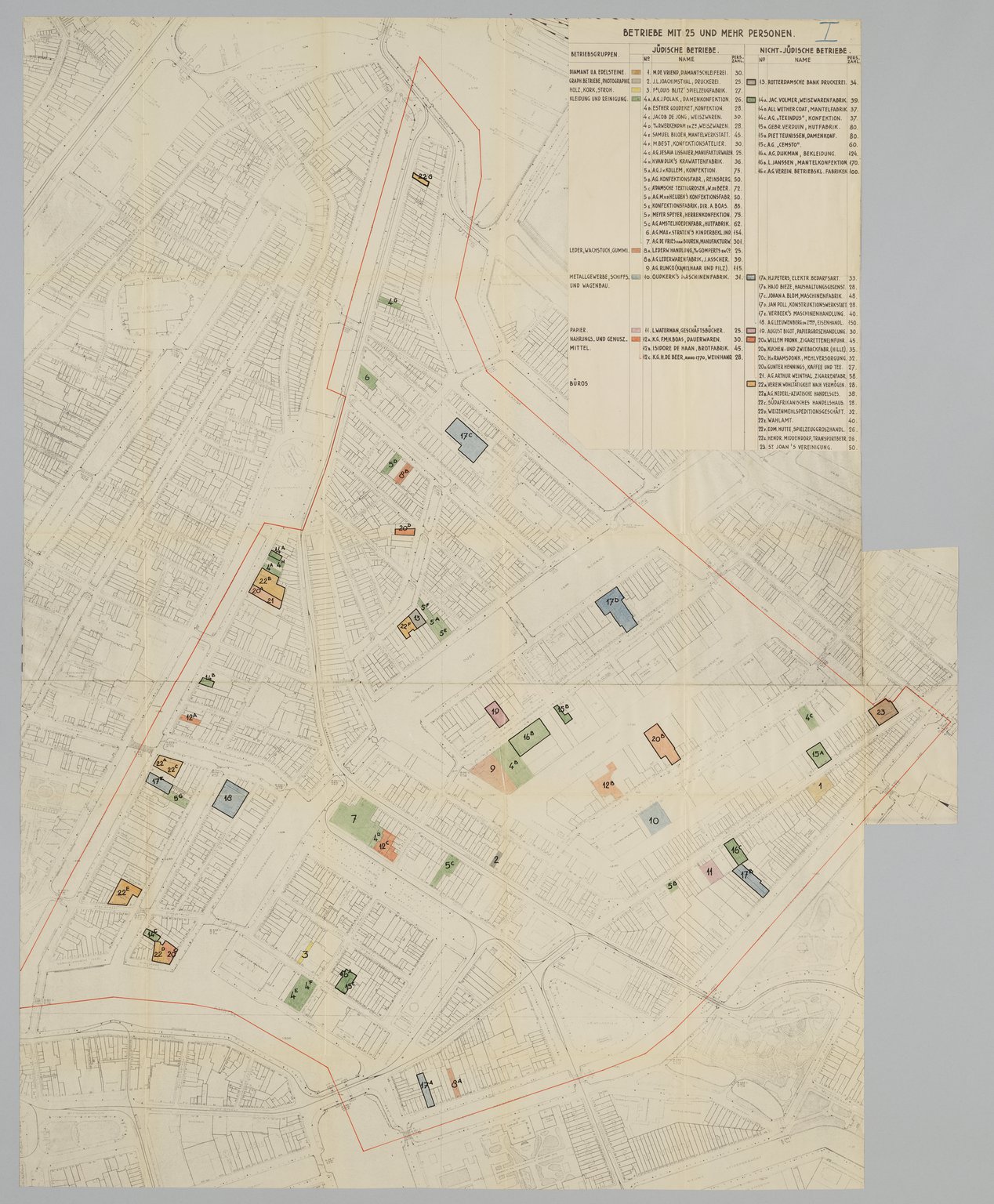

May 1941Amsterdam

May 1941AmsterdamThe Amsterdam municipality maps out where the Jews live

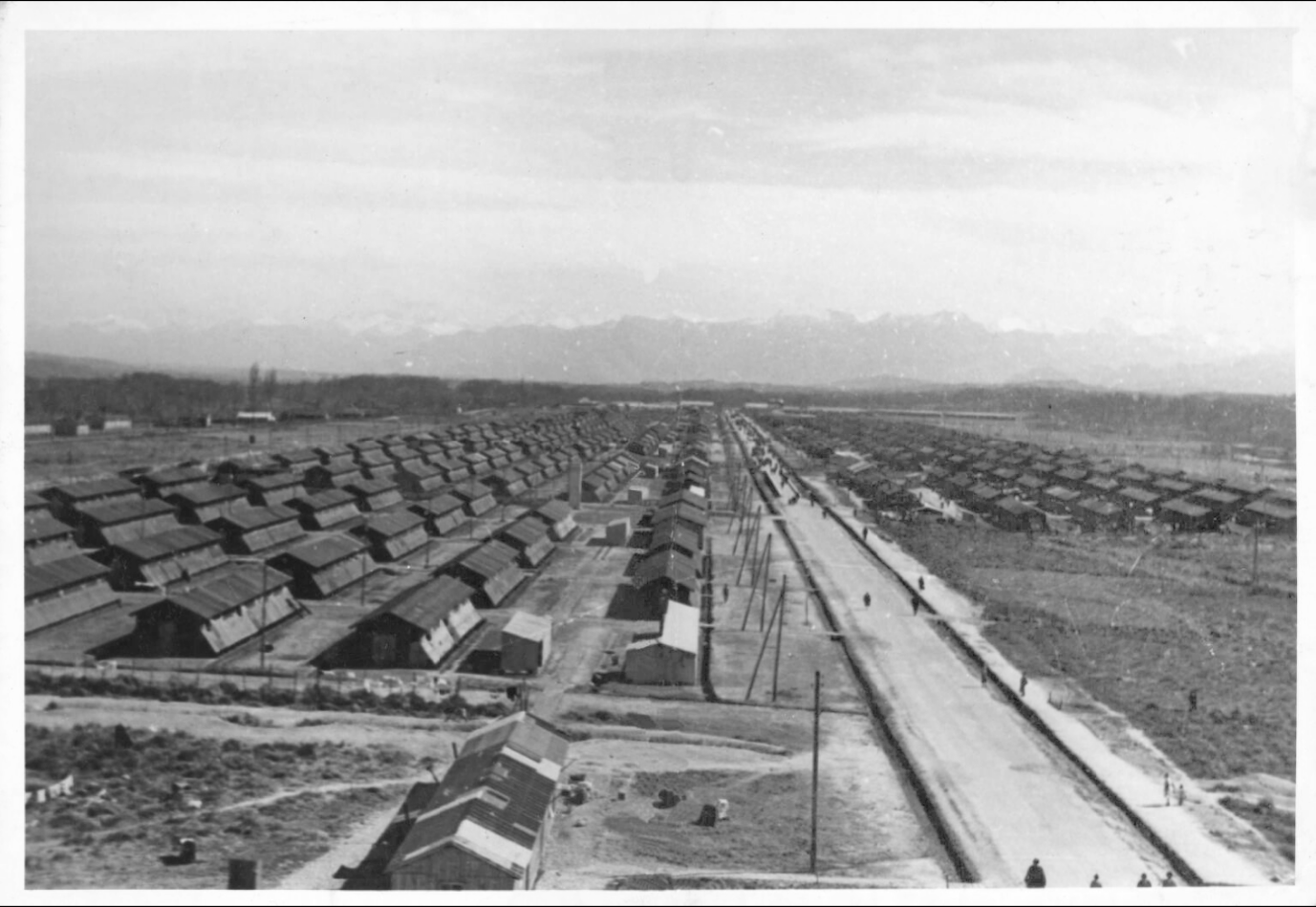

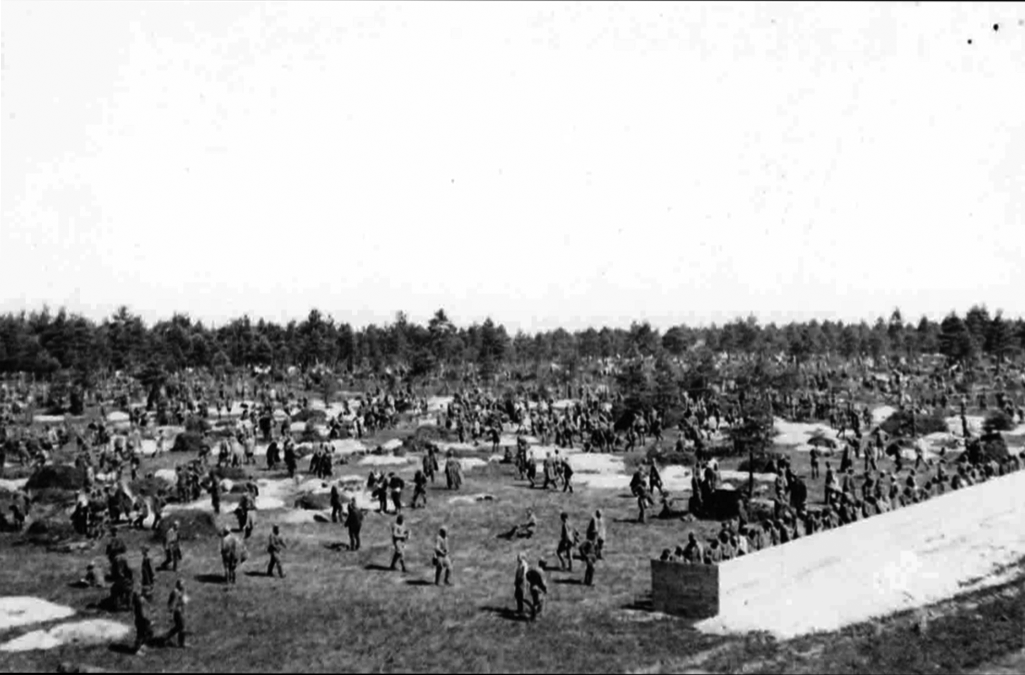

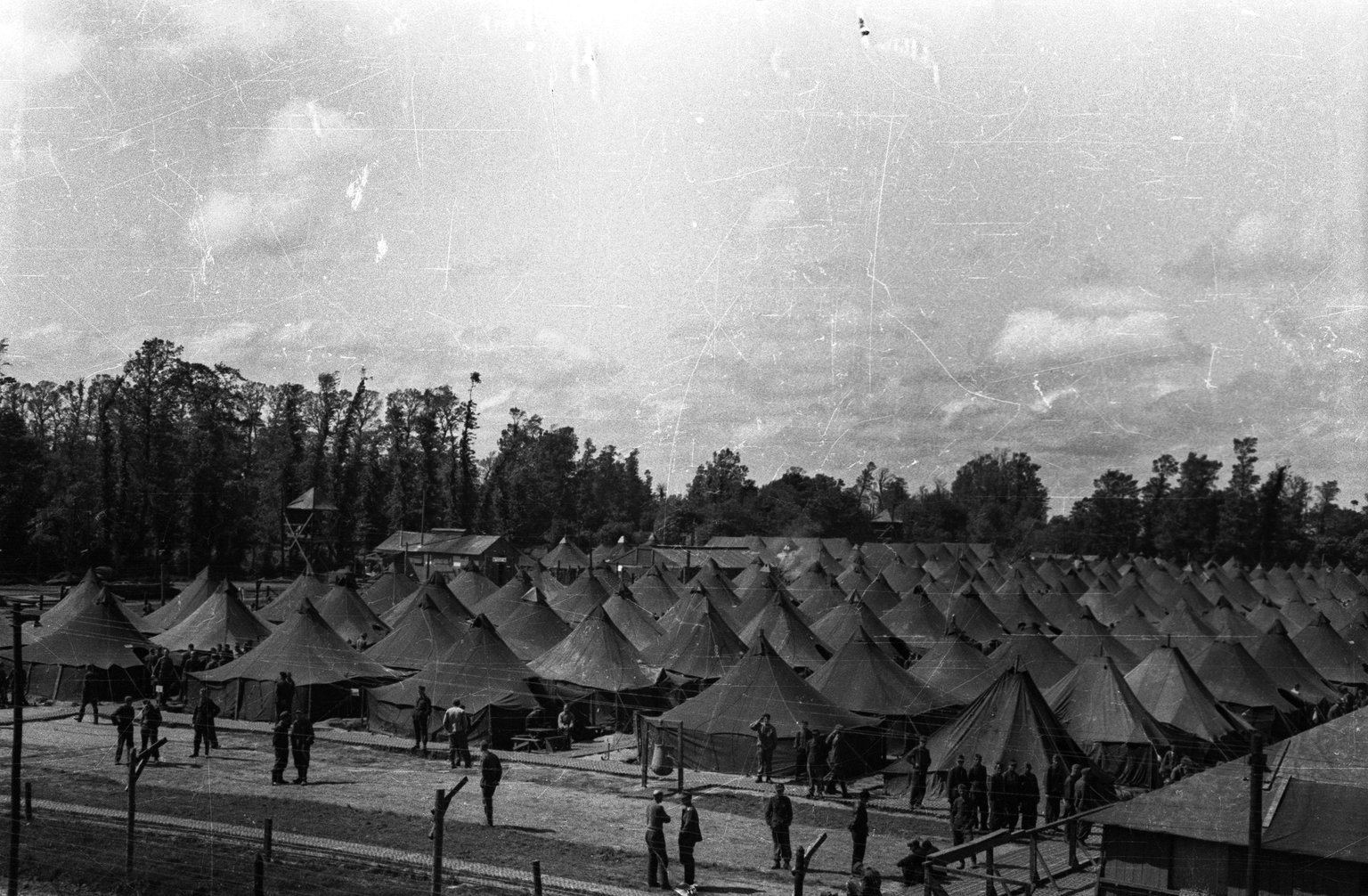

May-June 1940Bergen-Belsen

May-June 1940Bergen-BelsenSoviet prisoners of war at the Bergen-Belsen camp

Spring 1941The Netherlands

Spring 1941The NetherlandsV for Victory

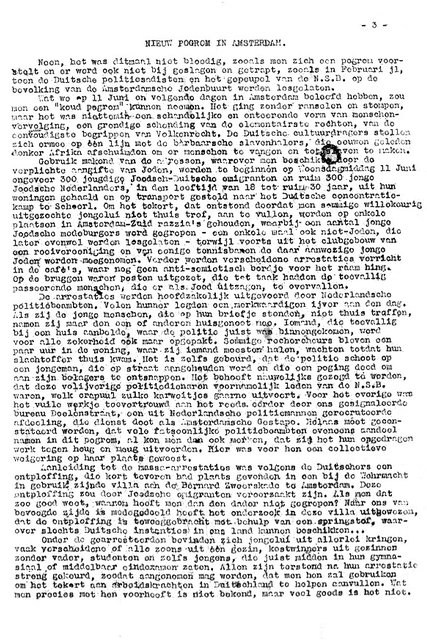

June 11, 1941Amsterdam

June 11, 1941AmsterdamRazzia on Jewish men in Amsterdam

June 22, 1941Soviet Union

June 22, 1941Soviet UnionOperation Barbarossa: Germany invades the Soviet Union

July 1941Trawniki

July 1941TrawnikiTrawniki: training camp for camp guards

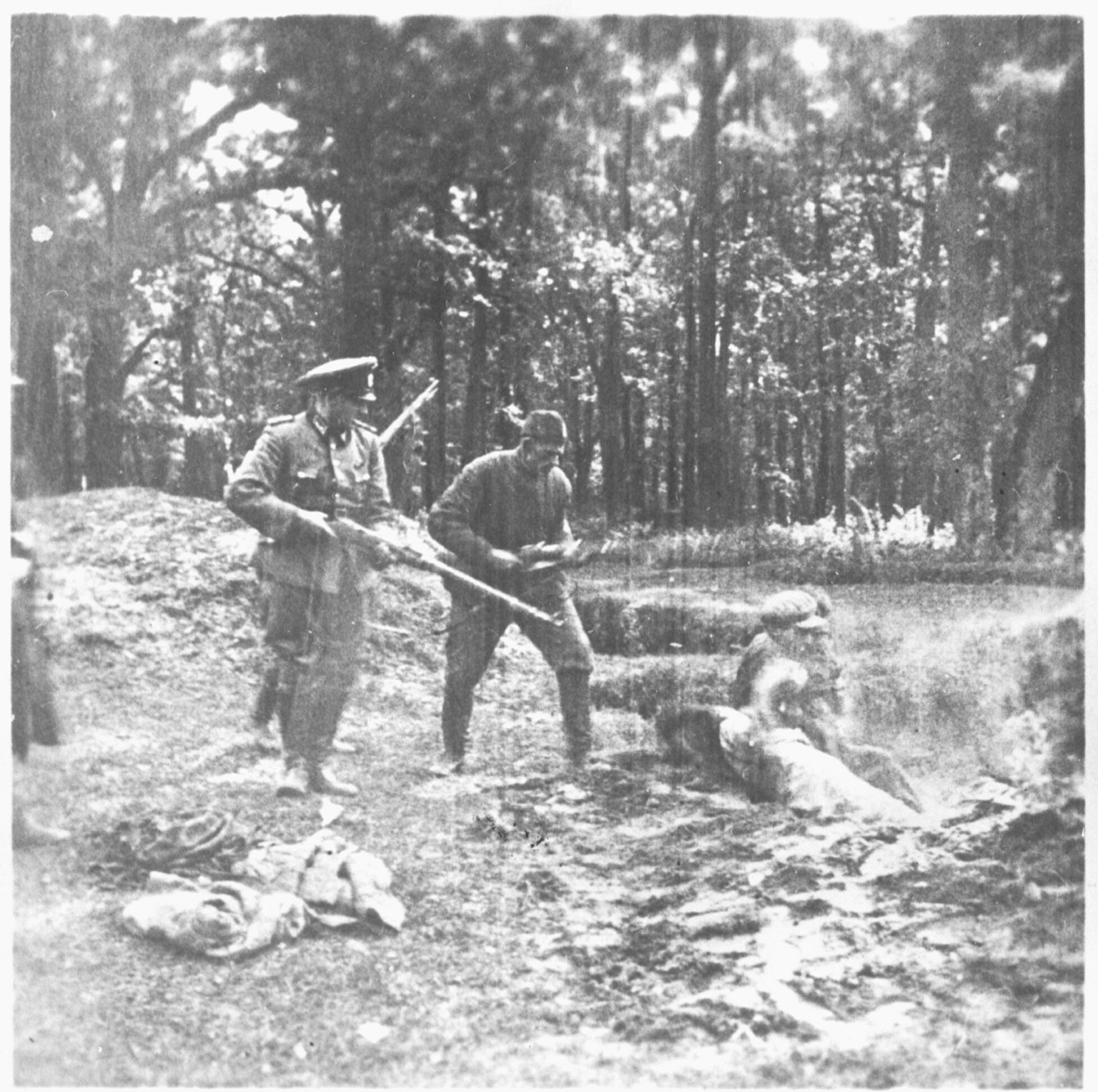

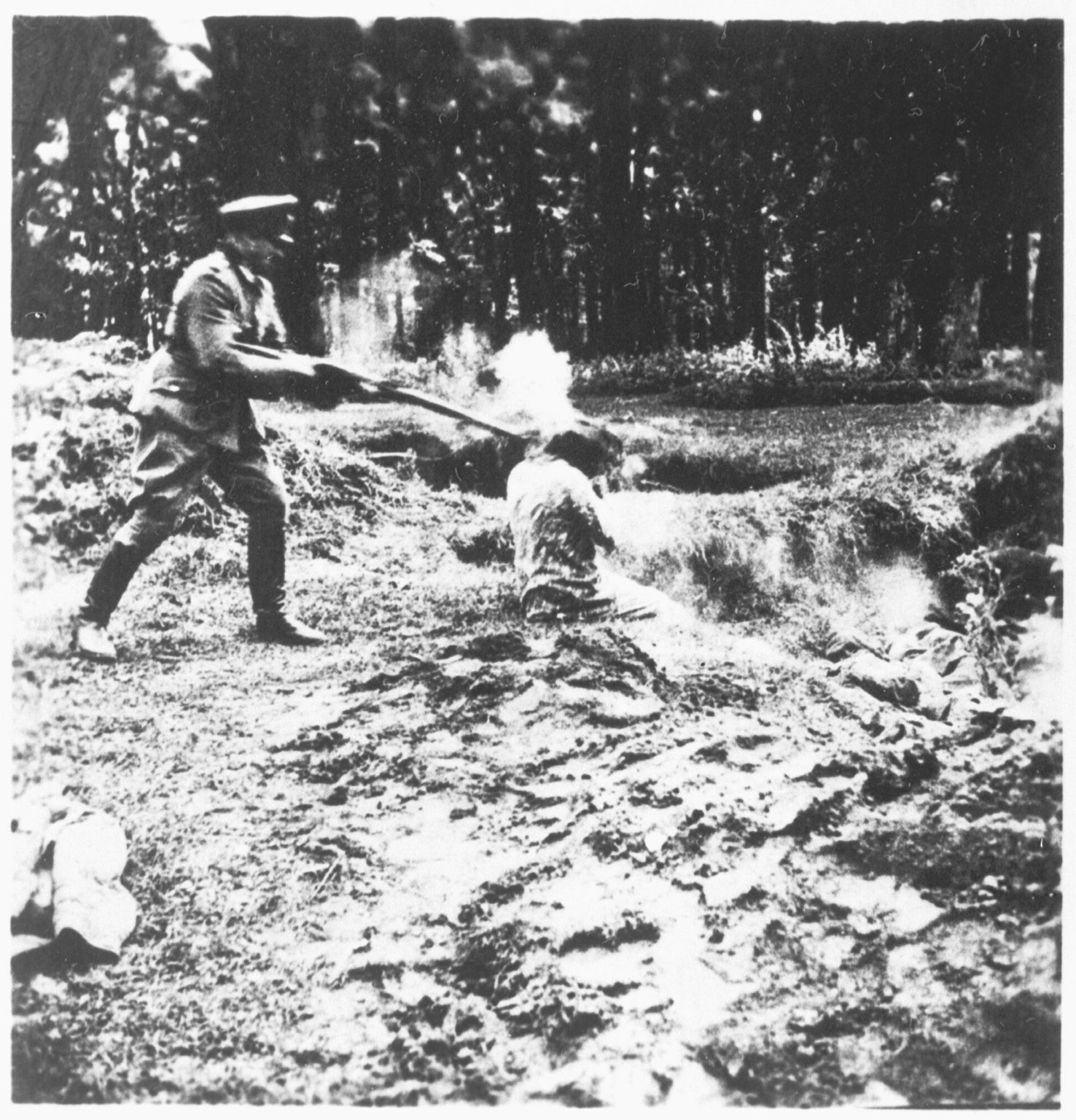

1941-1942Soviet Union

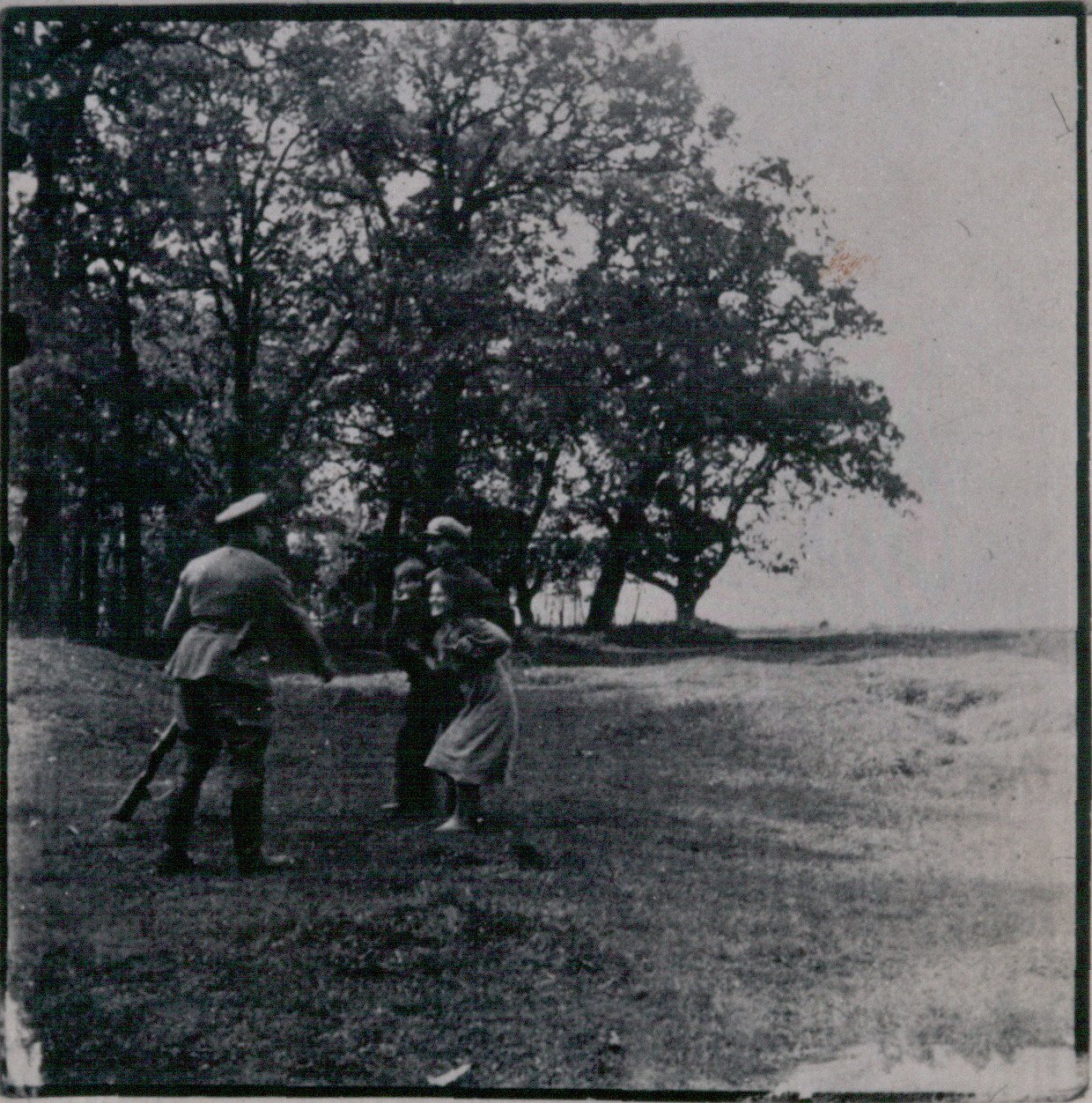

1941-1942Soviet UnionEinsatzgruppen: special death squads

July 1941Rotterdam

July 1941RotterdamAmerican consulate is closed: escape no longer possible

July 26, 1941The Hague

July 26, 1941The HagueDutch volunteers in the Waffen-SS

Aug. 8, 1941Amsterdam

Aug. 8, 1941AmsterdamDutch Jews are robbed

september 1941Amsterdam

september 1941AmsterdamMarkets for Jews only

Sept. 1, 1941Amsterdam

Sept. 1, 1941AmsterdamJewish children are made to go to separate schools

October 1941Moscow

October 1941MoscowThe German army gets stuck in the Soviet Union

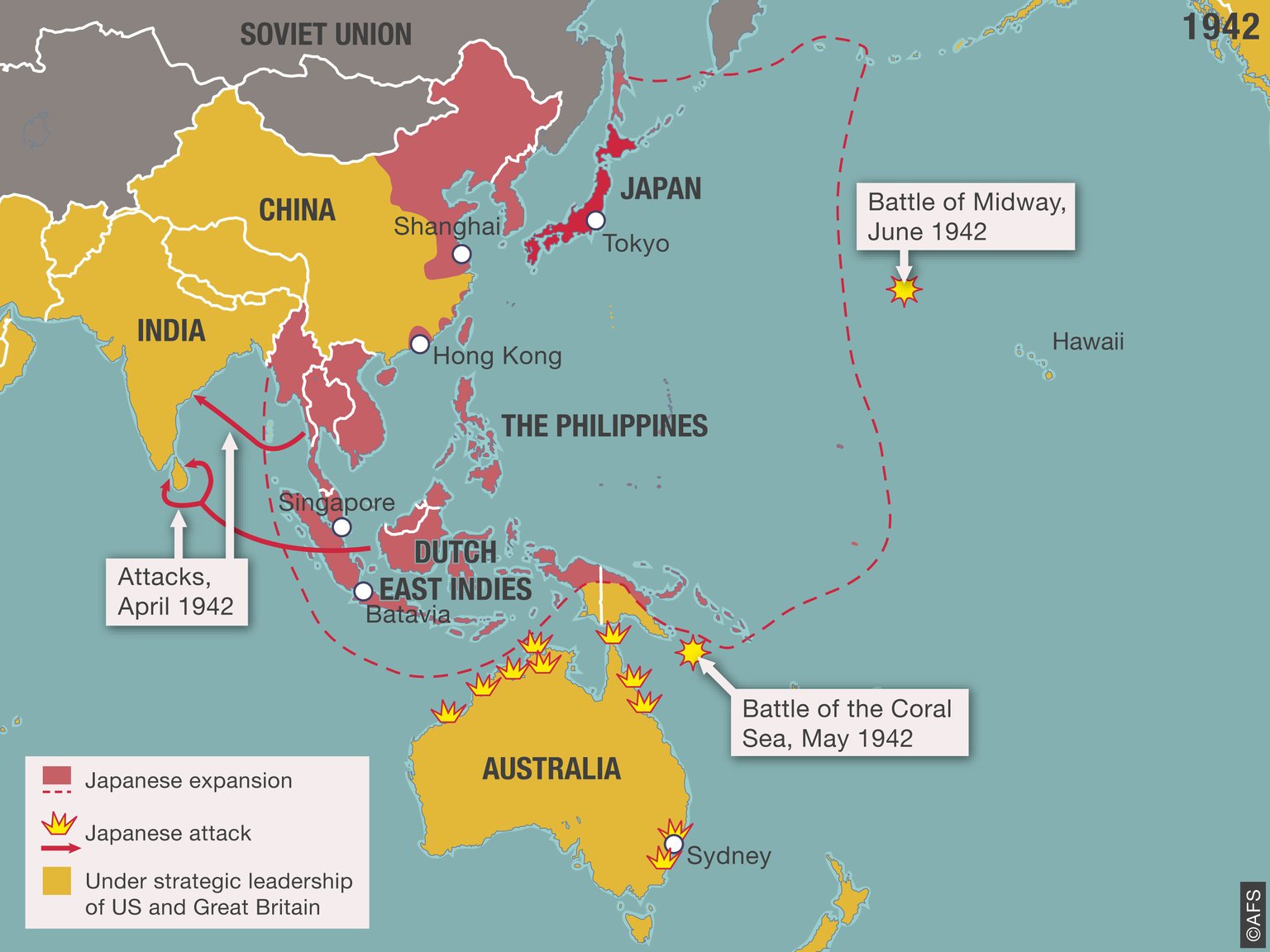

Dec. 7, 1941Pearl Harbor

Dec. 7, 1941Pearl HarborJapan bombs Pearl Harbor: Hitler declares war on the US

1941-1945Pacific and Asia

1941-1945Pacific and AsiaMaps of the war in Asia

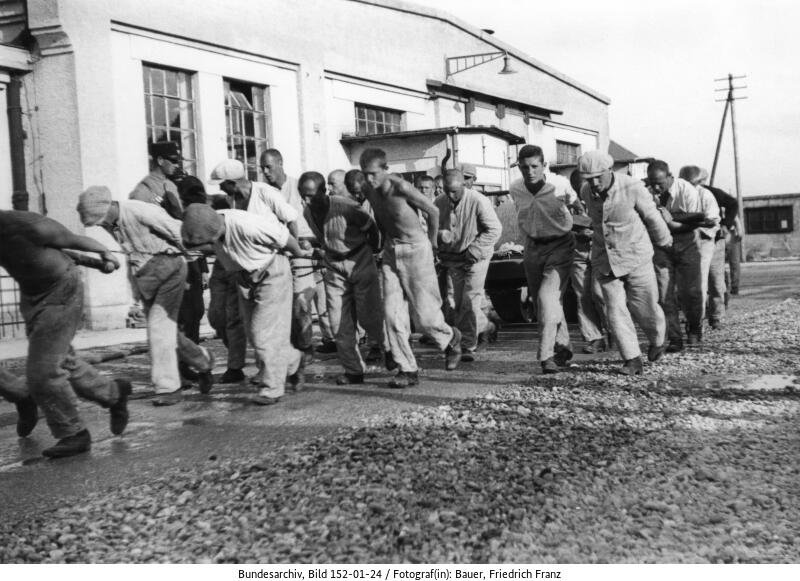

Jan. 10, 1942Amsterdam

Jan. 10, 1942AmsterdamJewish men are sent to labour camps

Jan. 20, 1942Wannsee, Berlin

Jan. 20, 1942Wannsee, BerlinWannsee Conference. Nazis organise the murder of European Jews

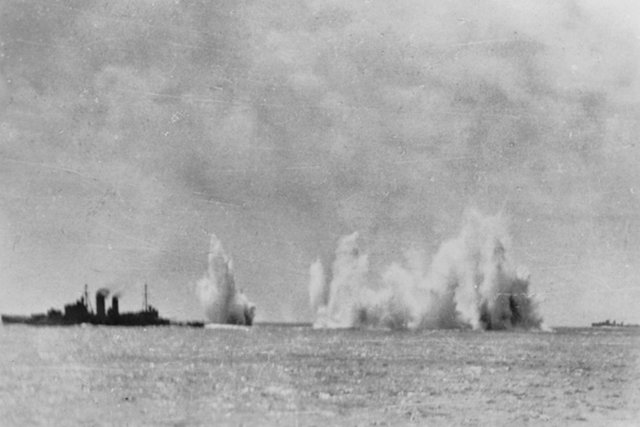

Feb. 27, 1942Dutch East Indies

Feb. 27, 1942Dutch East IndiesBattle of the Java Sea

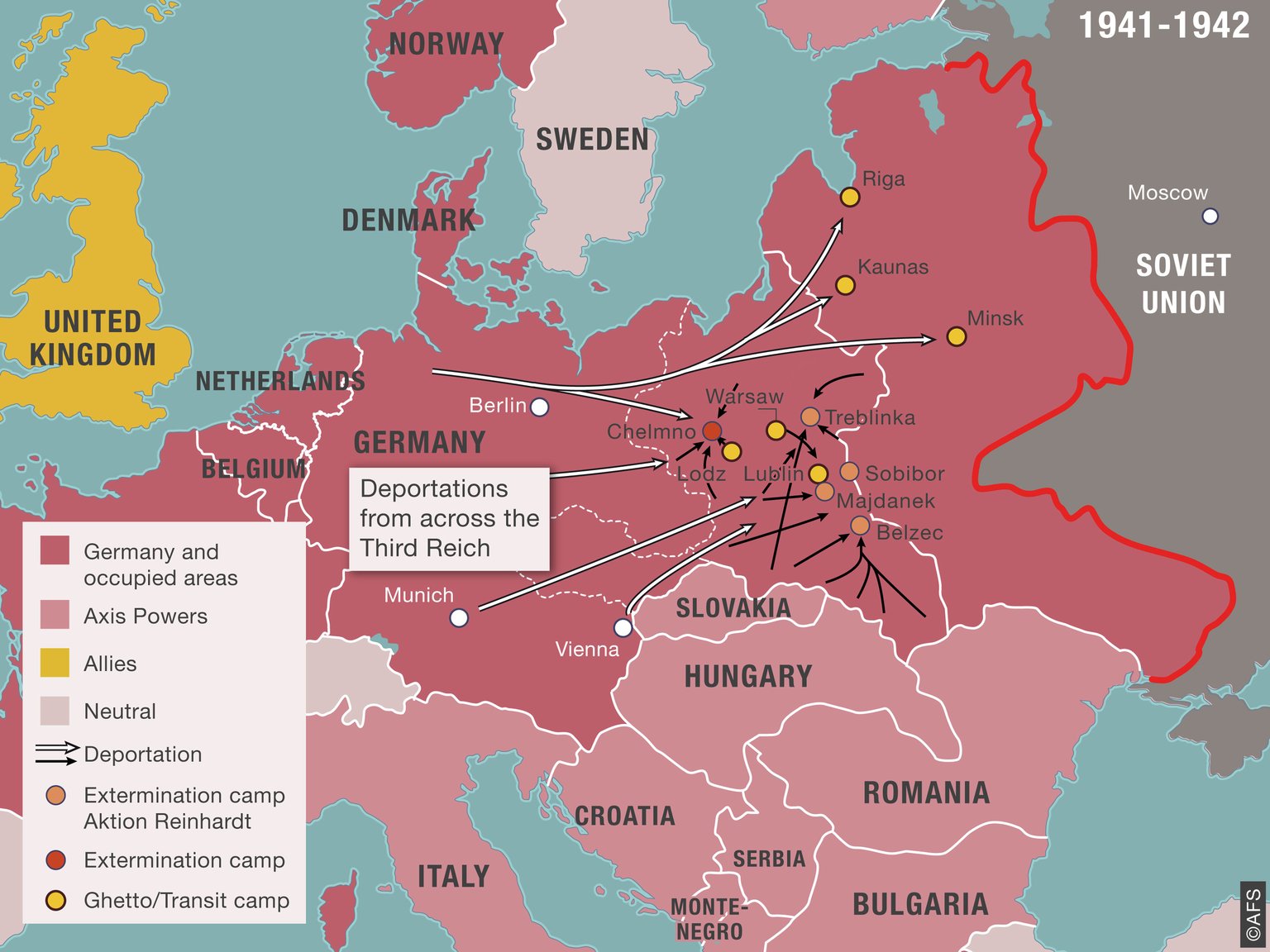

1942 - 1943Occupied Poland

1942 - 1943Occupied PolandAktion Reinhard: murder of the Jews in occupied Poland

March 9, 1942Dutch East Indies

March 9, 1942Dutch East IndiesJapan occupies the Dutch East Indies

March 1942Auschwitz-Birkenau

March 1942Auschwitz-BirkenauAuschwitz concentration and extermination camp

April 10, 1942Philippines

April 10, 1942PhilippinesPrisoners of war and internment camps in Japan

April 17, 1942Amsterdam

April 17, 1942AmsterdamJewish diamond traders are searched

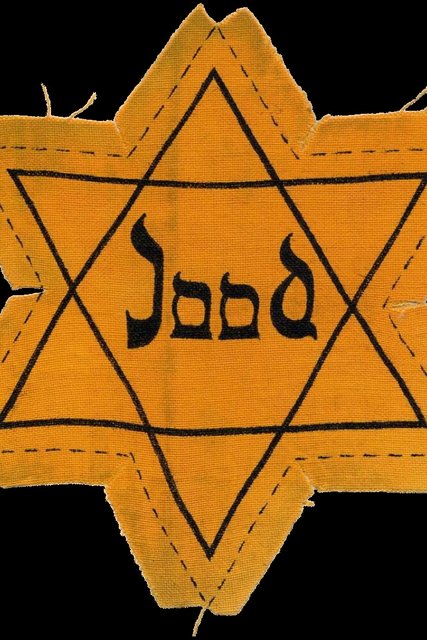

May 3, 1942The Netherlands

May 3, 1942The NetherlandsThe introduction of the yellow badge in the Netherlands

May 18, 1942Museumplein, Amsterdam

May 18, 1942Museumplein, AmsterdamHeinrich Himmler in Amsterdam

June 1, 1942Amsterdam

June 1, 1942AmsterdamEstablishment of the Jewish Affairs Office

June 12, 1942Amsterdam

June 12, 1942AmsterdamAnne receives a diary

June 30, 1942The Netherlands

June 30, 1942The NetherlandsForbidden for Jews

July 6, 1942Amsterdam

July 6, 1942AmsterdamThe Frank family goes into hiding

July 13, 1942Amsterdam

July 13, 1942AmsterdamThe Van Pels family goes into hiding

July 15, 1942Amsterdam

July 15, 1942AmsterdamThe deportations to Auschwitz have begun

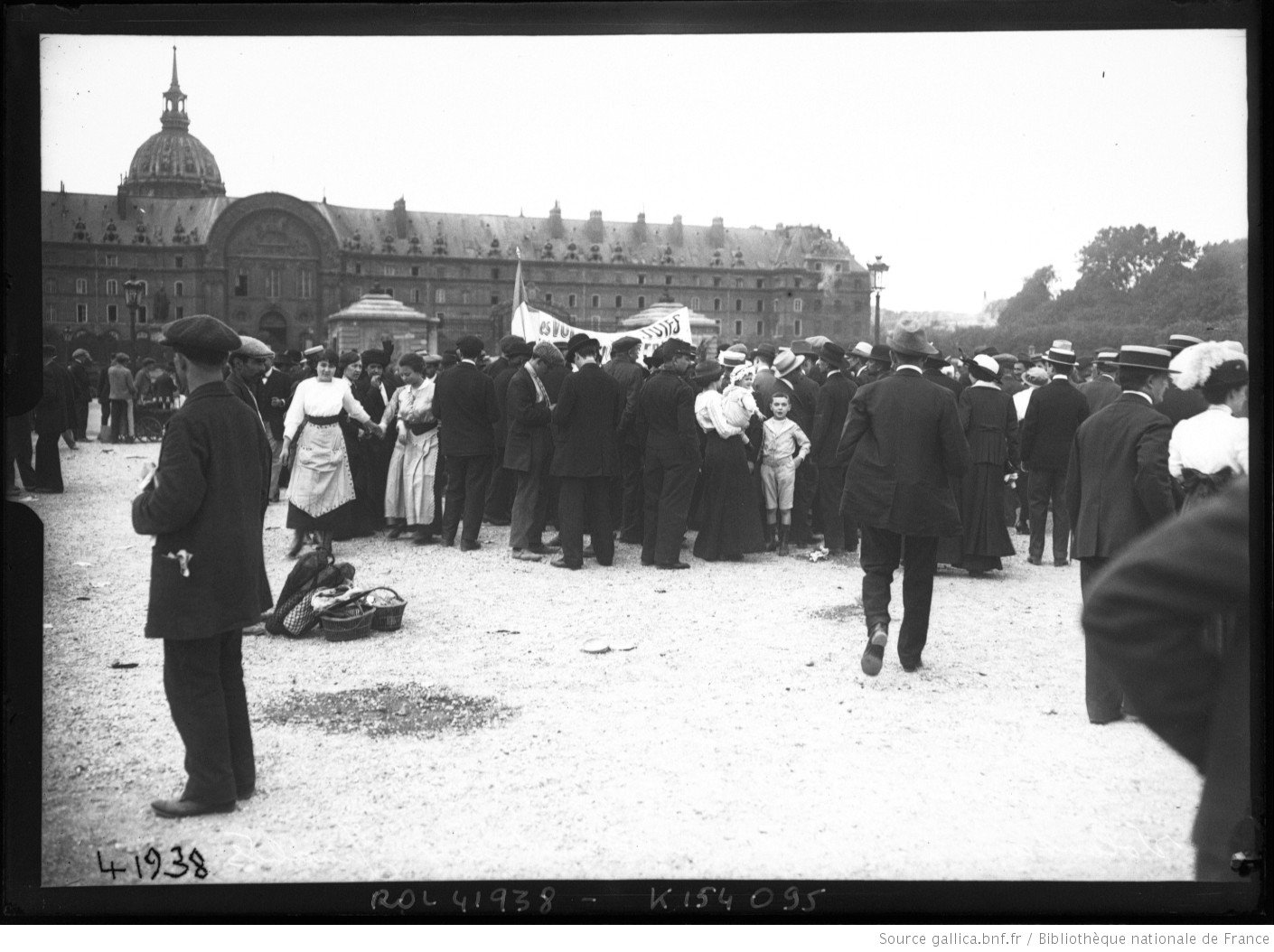

16 and 17 July 1942Paris

16 and 17 July 1942ParisMajor raid in Paris

August 1942Amsterdam

August 1942AmsterdamThe Hollandsche Schouwburg becomes a deportation centre for Jews

Sept. 21, 1942Amsterdam

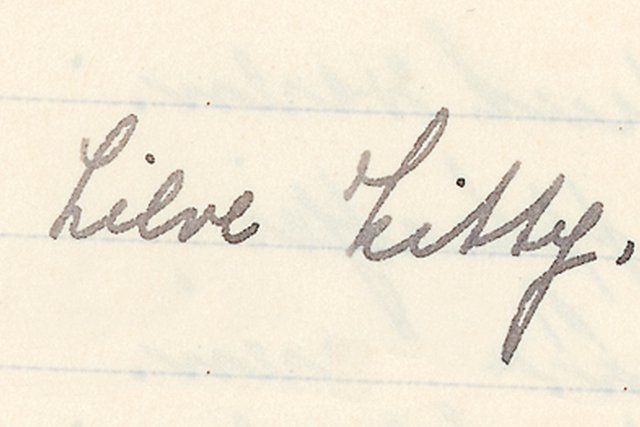

Sept. 21, 1942AmsterdamKitty and the other friends in the diary

Oct. 2, 1942Westerbork

Oct. 2, 1942WesterborkWesterbork becomes overcrowded: Deception on Simchat Torah

November 1942Winterswijk

November 1942WinterswijkFoundation of the National Organisation to Help those in Hiding

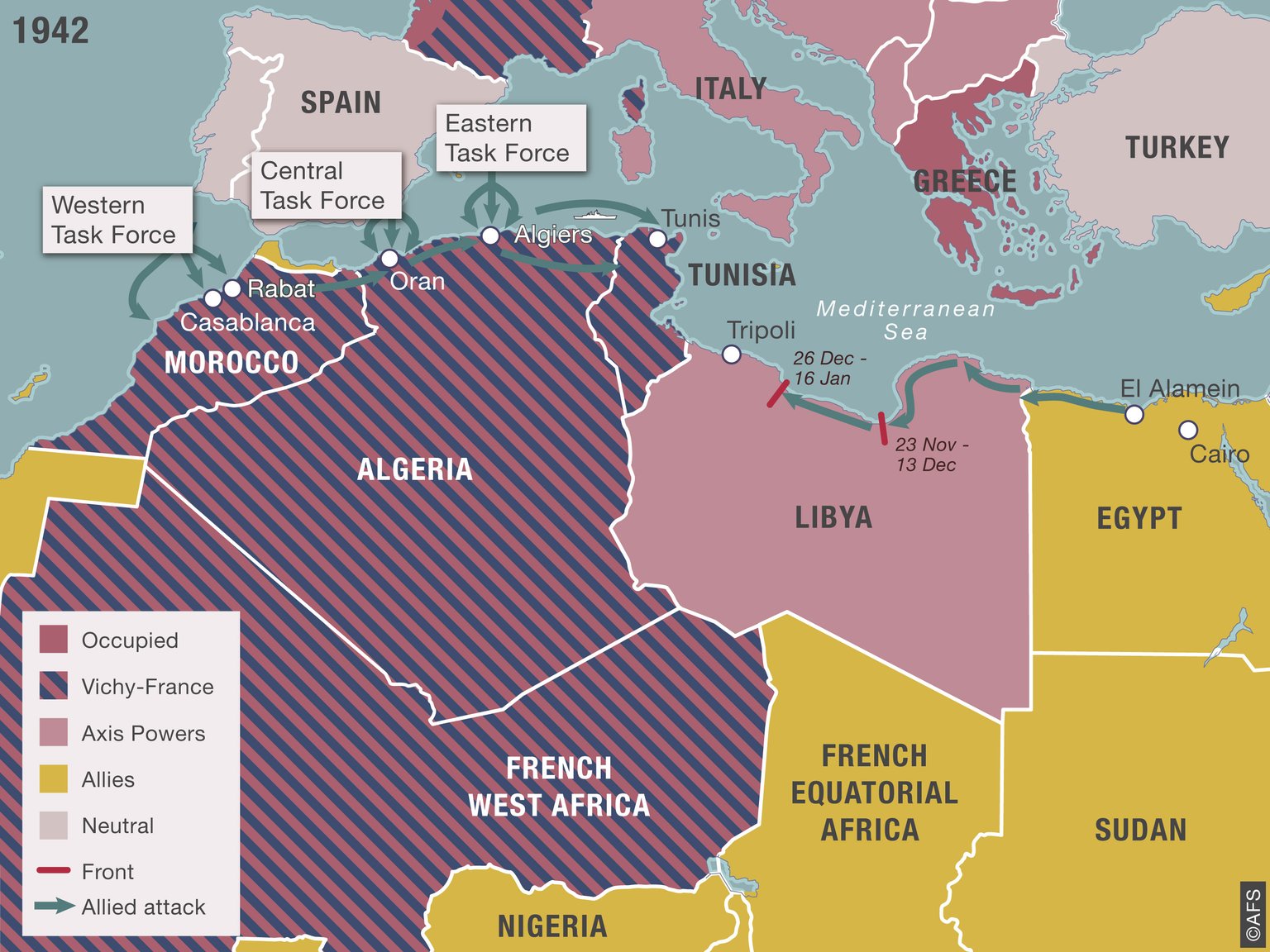

November 1942North Africa

November 1942North AfricaAllied victories in North Africa

Nov. 16, 1942Amsterdam

Nov. 16, 1942AmsterdamFritz Pfeffer goes into hiding

Dec. 6, 1942Eindhoven

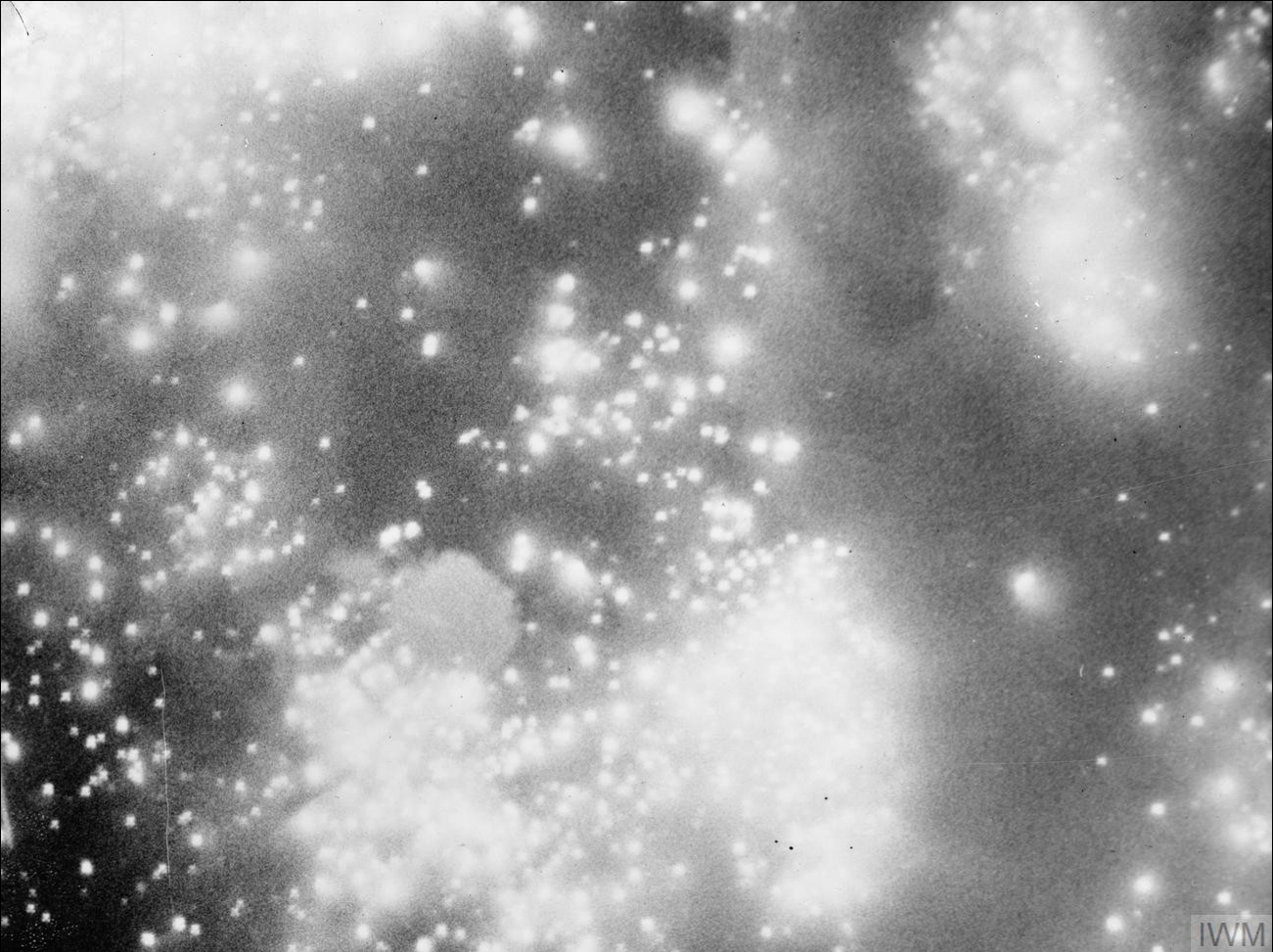

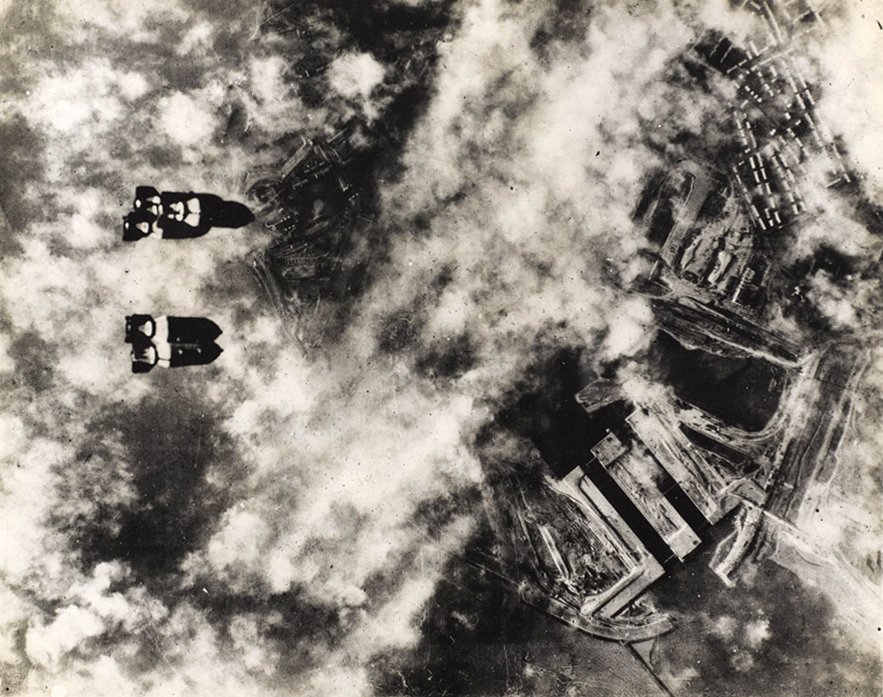

Dec. 6, 1942EindhovenBombing the Philips factories in Eindhoven

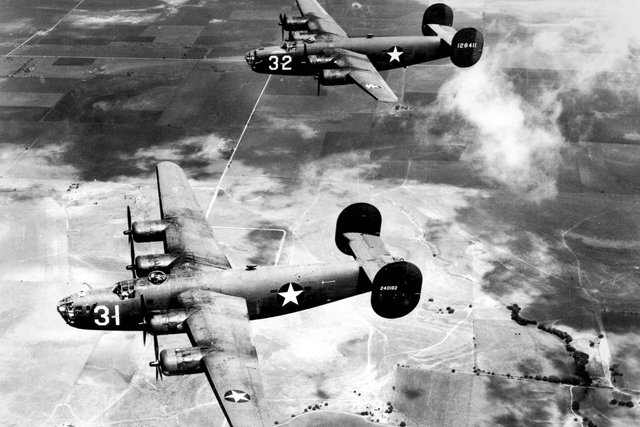

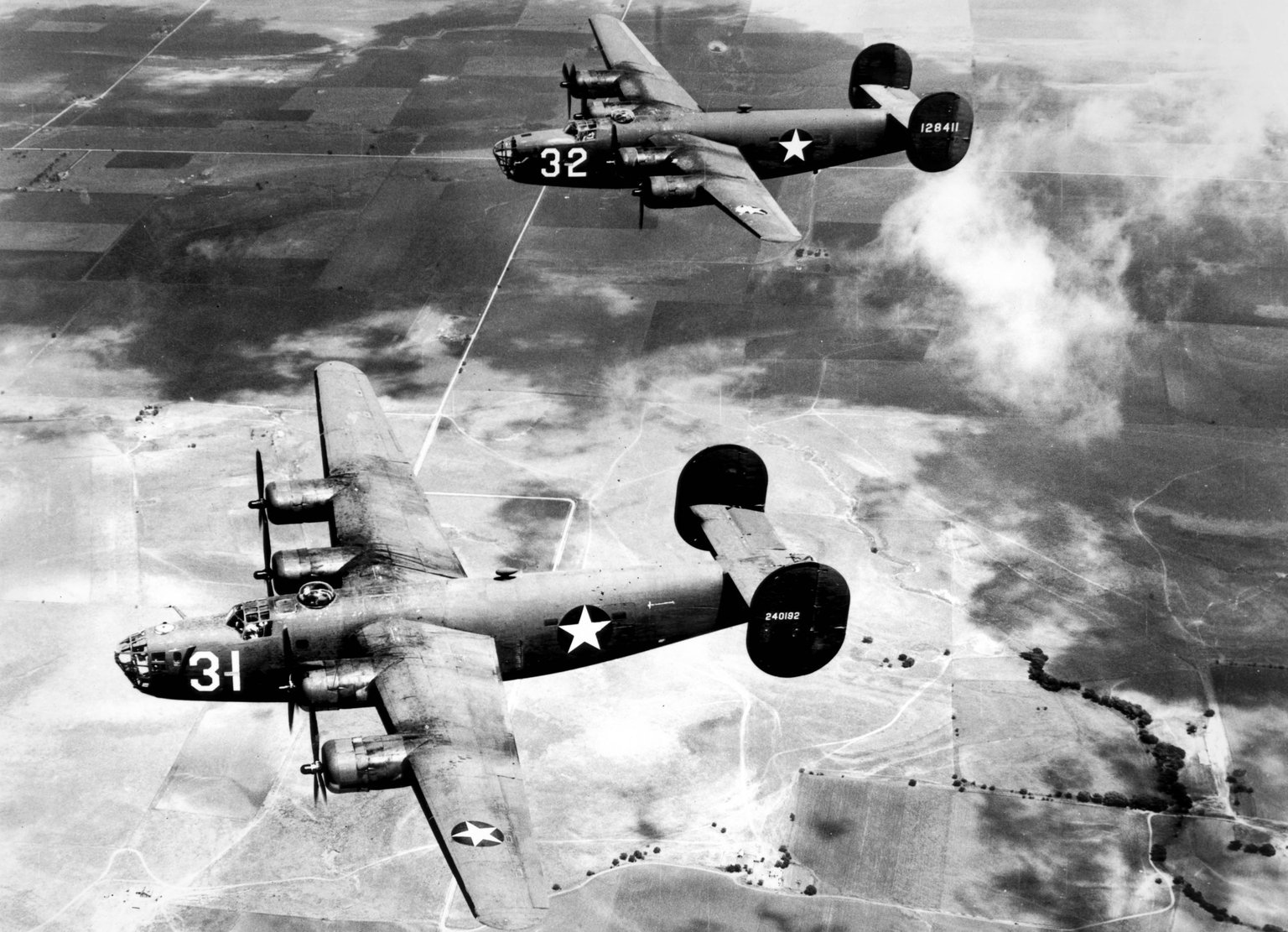

Jan. 27, 1943Wilhelmshaven, Duitsland

Jan. 27, 1943Wilhelmshaven, DuitslandUS Air Force bombs Germany

February 1943Stalingrad

February 1943StalingradThe Battle of Stalingrad: Germany humiliated

March 27, 1943Amsterdam

March 27, 1943AmsterdamThe Resistance attacks the population register of Amsterdam

March 29, 1943The Netherlands

March 29, 1943The NetherlandsRauter wants to run all Jews from the provinces

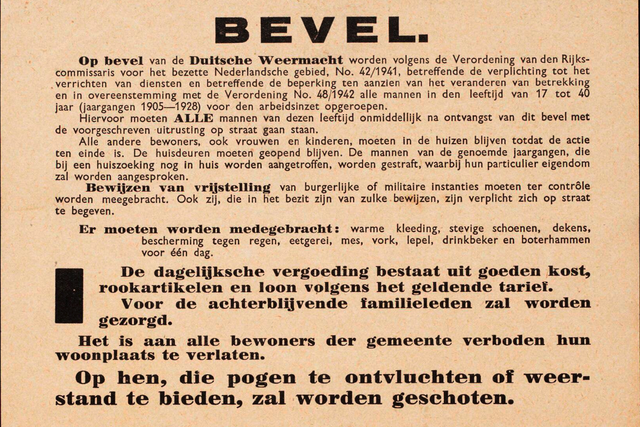

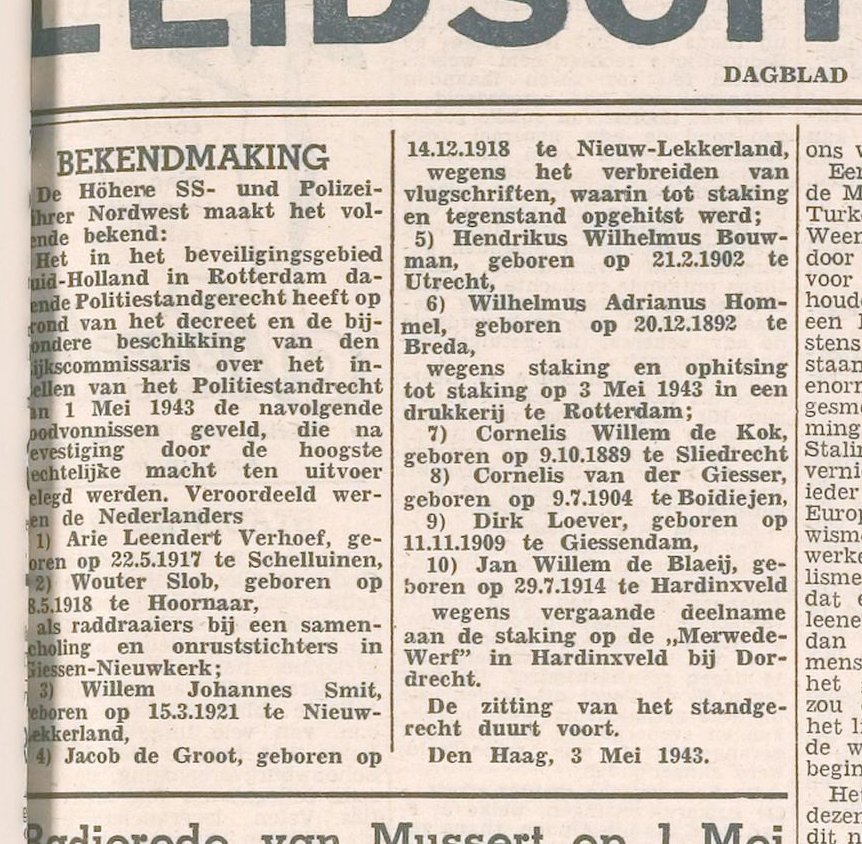

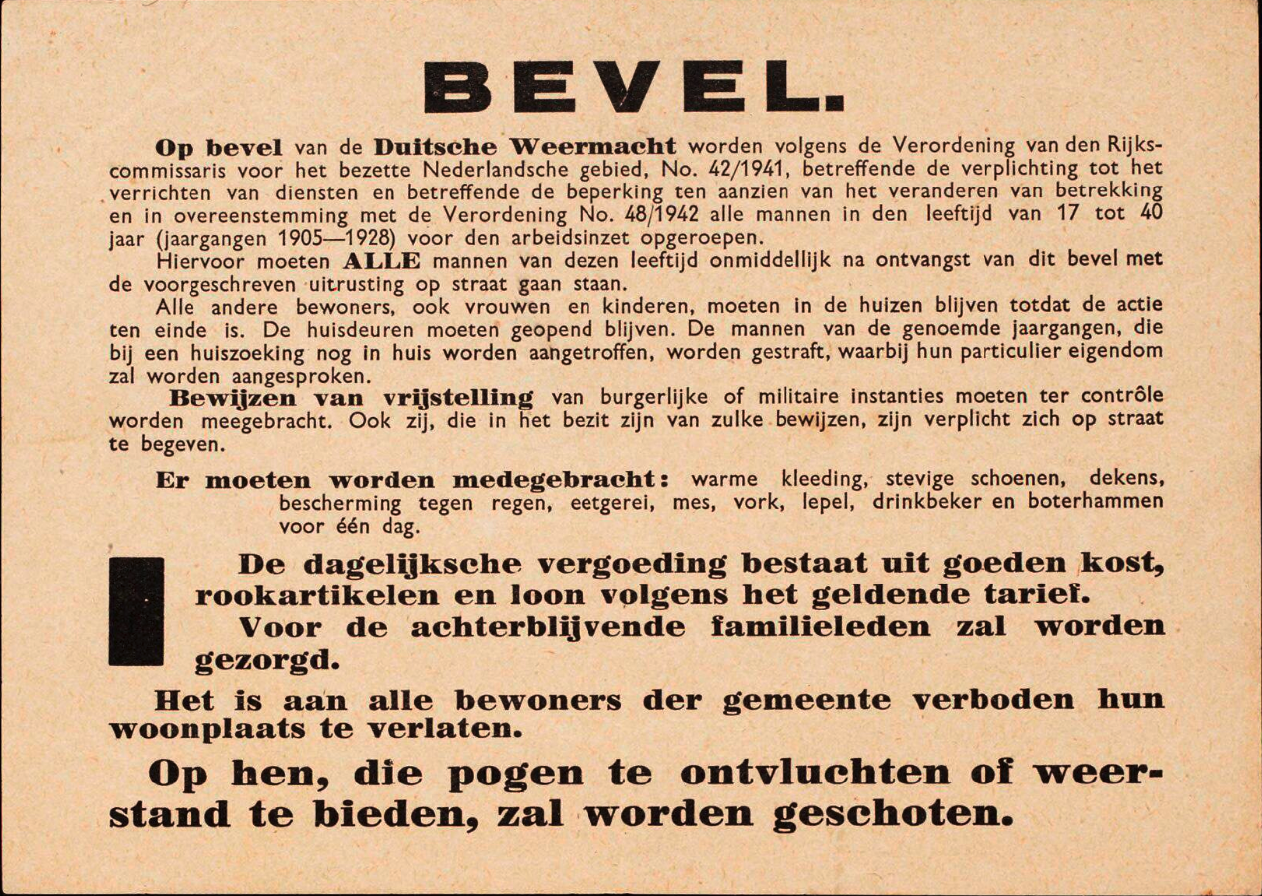

April 29, 1943The Netherlands

April 29, 1943The NetherlandsApril-May strikes

May 8, 1943The Netherlands

May 8, 1943The NetherlandsMandatory registration for forced labour

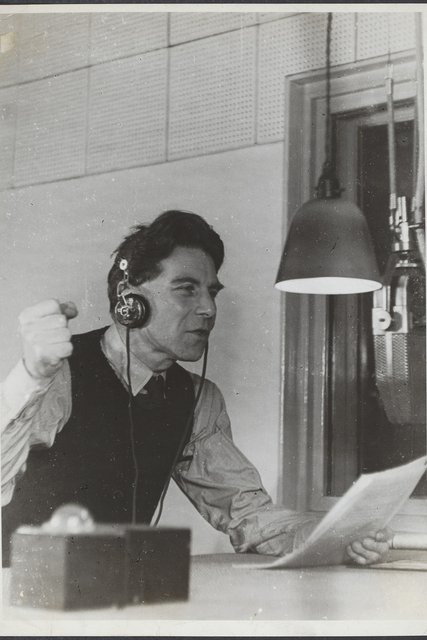

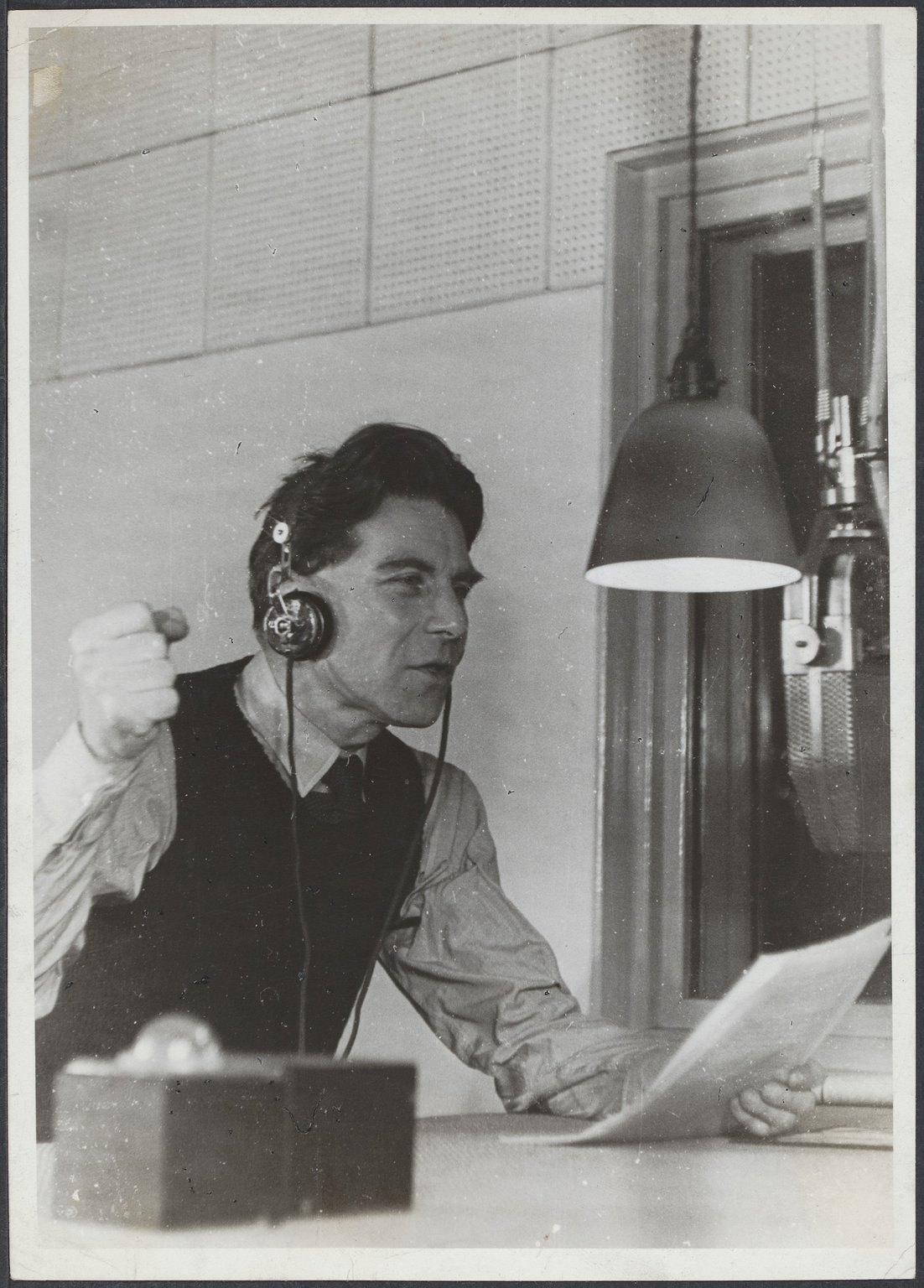

May 10, 1943London

May 10, 1943LondonRadio Oranje: ‘The voice of the Netherlands at war’

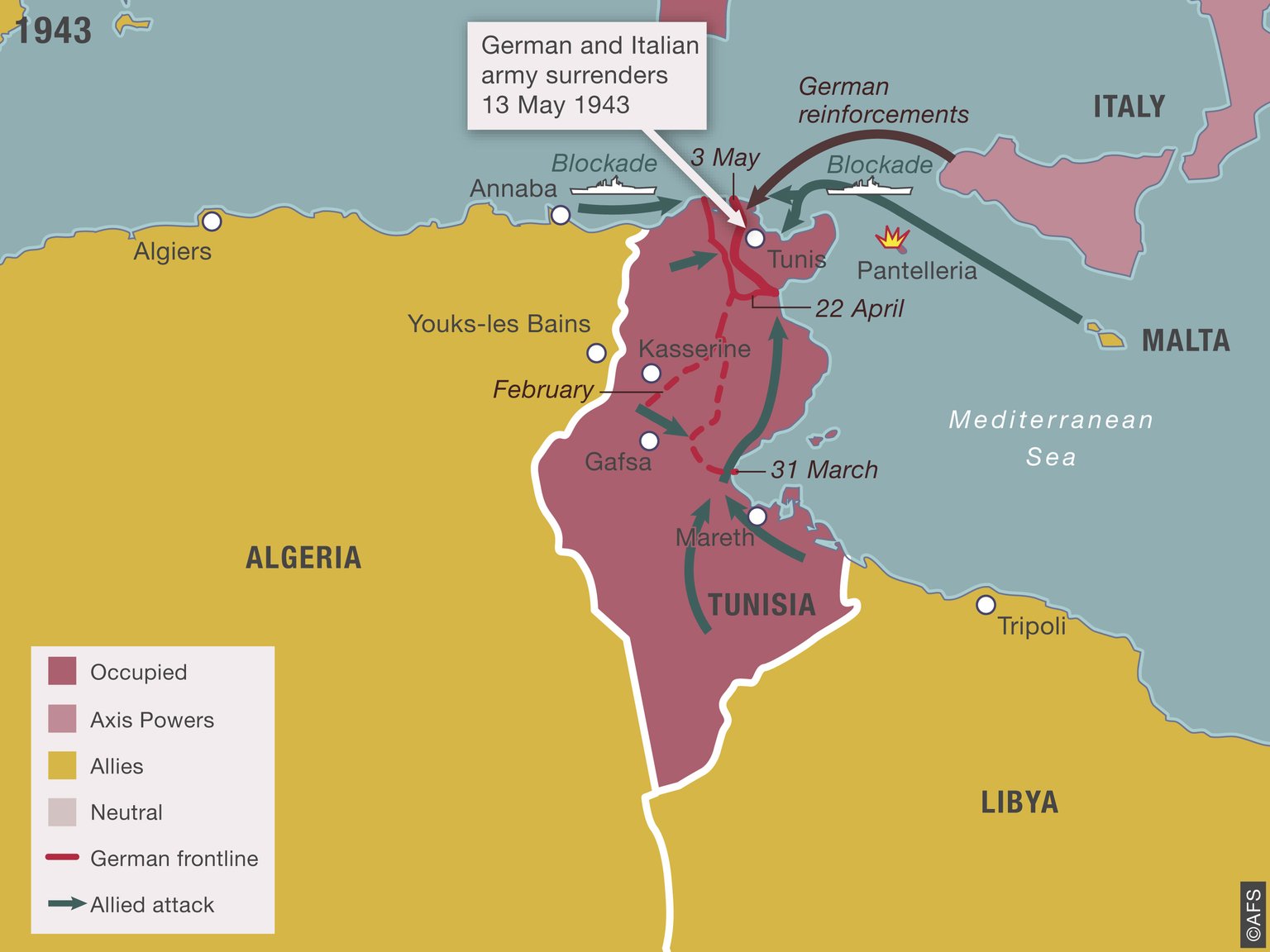

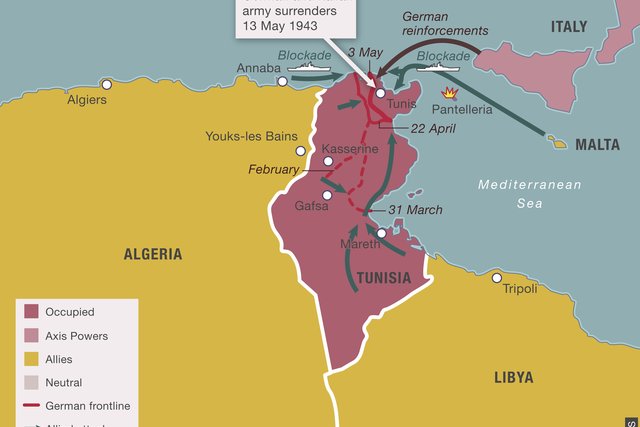

1942-1943North Africa

1942-1943North AfricaGerman surrender in North Africa

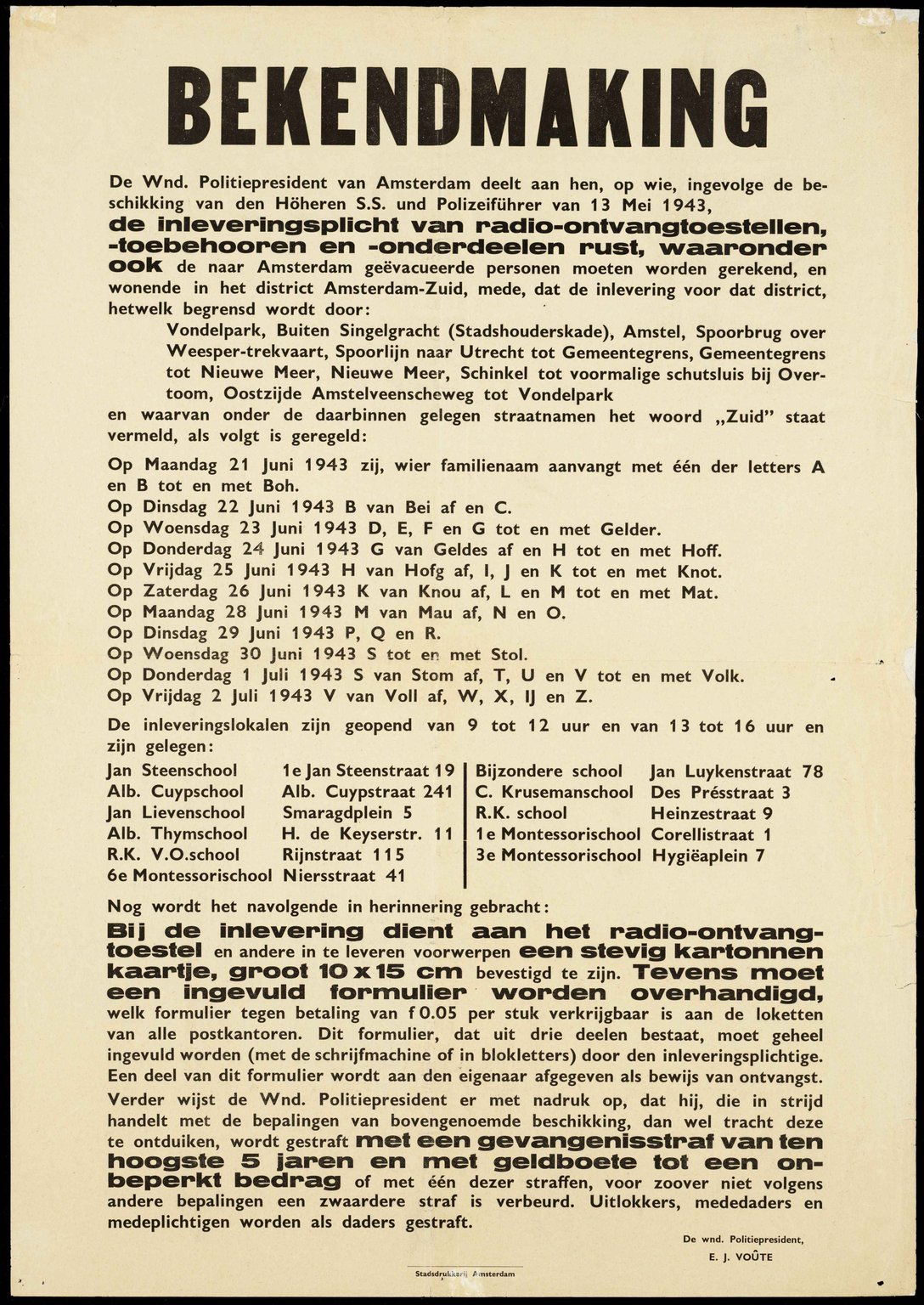

May 20, 1943Polderweg, Amsterdam

May 20, 1943Polderweg, AmsterdamAll Jews must leave Amsterdam

June 20, 1943Amsterdam

June 20, 1943AmsterdamLast raids in Amsterdam: 17,000 Jews arrested

1942-1945The Netherlands

1942-1945The NetherlandsHunting for Jews

juli 1943Amsterdam

juli 1943AmsterdamJewish children rescued from the Hollandsche Schouwburg

July 10, 1943Sicily

July 10, 1943SicilyThe Allied Forces land on Sicily

July 17, 1943Amsterdam

July 17, 1943AmsterdamAllied bombs on Amsterdam

September 1943Amsterdam

September 1943AmsterdamNorbert Klein is rescued from hospital

Nov. 20, 1943Gilbert Islands

Nov. 20, 1943Gilbert IslandsThe Battle of Tarawa

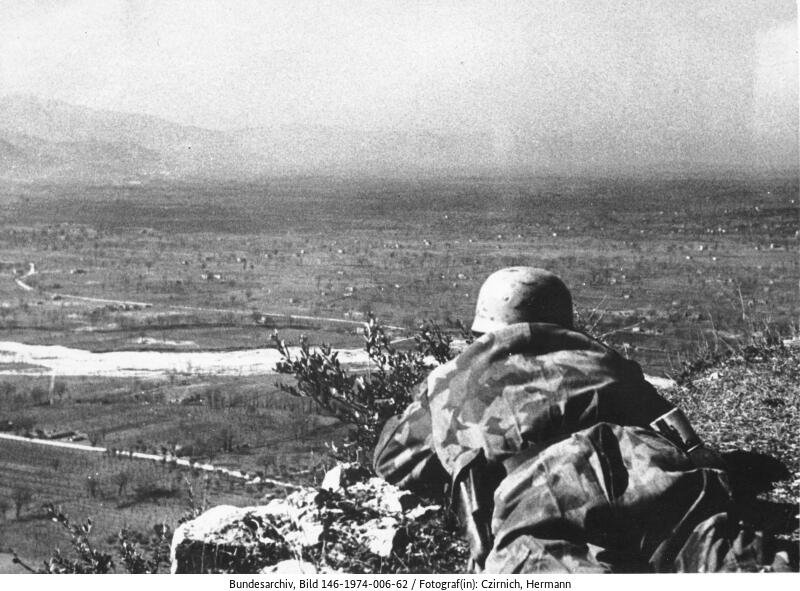

January - May 1944Monte Cassino, Italië

January - May 1944Monte Cassino, ItaliëBattle of Monte Cassino

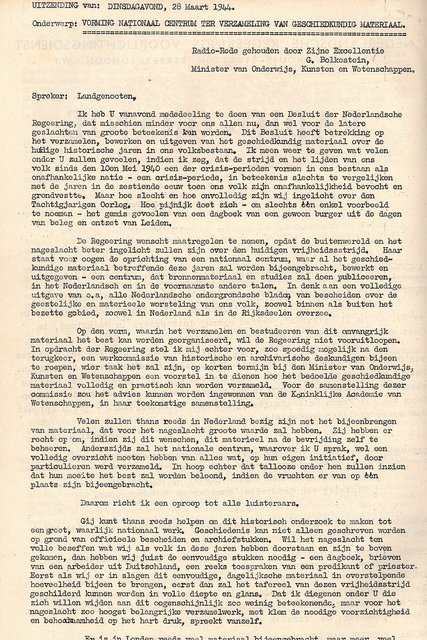

March 28, 1944Amsterdam

March 28, 1944AmsterdamAfter an appeal from a Dutch Minister, Anne wants to publish her diary

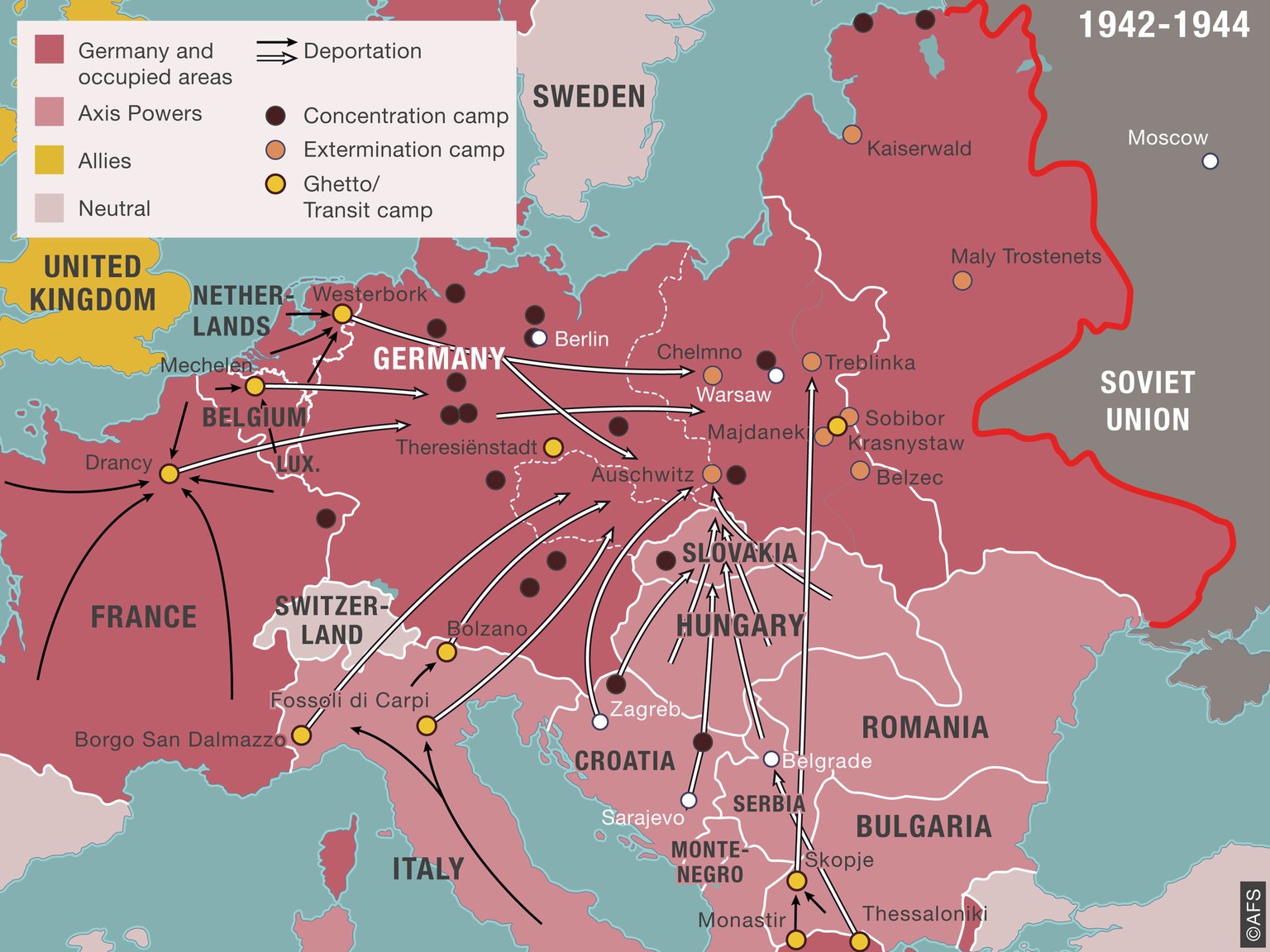

May 26, 1944Hungary

May 26, 1944HungaryDeportation of Hungarian Jews

June 6, 1944Normandy

June 6, 1944NormandyD-Day: The Allied Forces land in France

July 20, 1944Germany

July 20, 1944GermanyGerman officers attempt to assassinate Hitler

July 22, 1944Lublin

July 22, 1944LublinRed Army discovers Majdanek camp

Aug. 4, 1944Amsterdam

Aug. 4, 1944AmsterdamThe people in hiding are discovered: They are arrested and put in prison

Sept. 3, 1944Auschwitz-Birkenau

Sept. 3, 1944Auschwitz-BirkenauThe people from the Secret Annex are taken to Auschwitz

Sept. 5, 1944The Netherlands

Sept. 5, 1944The NetherlandsMad Tuesday: German soldiers and collaborators on the run

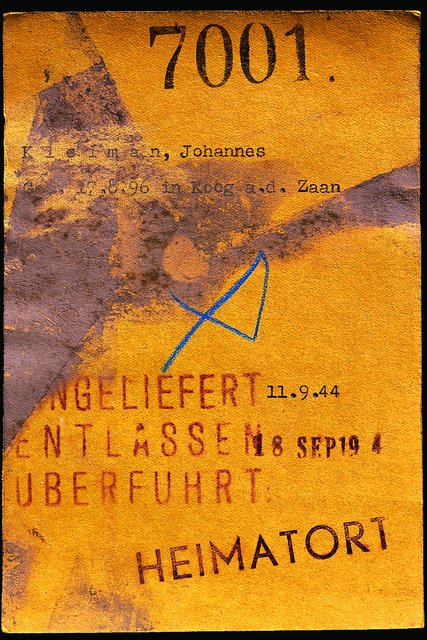

Sept. 11, 1944Amersfoort

Sept. 11, 1944AmersfoortKugler and Kleiman are sent to prison camp Amersfoort

September 1944Arnhem

September 1944ArnhemOperation Market Garden

Sept. 18, 1944Eindhoven

Sept. 18, 1944EindhovenEindhoven is liberated

Oct. 1, 1944Putten

Oct. 1, 1944PuttenThe Putten Raid

Nov. 1, 1944Auschwitz - Bergen-Belsen

Nov. 1, 1944Auschwitz - Bergen-BelsenAnne, Margot, and Auguste are taken to Bergen-Belsen

Nov. 10, 1944Margraten

Nov. 10, 1944MargratenAmerican military cemetery at Margraten

Nov. 28, 1944Antwerp

Nov. 28, 1944AntwerpThe Scheldt is open

December 1944The Netherlands

December 1944The NetherlandsHunger winter: hunger and cold in the Netherlands

Dec. 16, 1944Belgium

Dec. 16, 1944BelgiumHitler's last attack: The Battle of the Bulge

Winter 1945Germany

Winter 1945GermanyDeath marches from the concentration camps

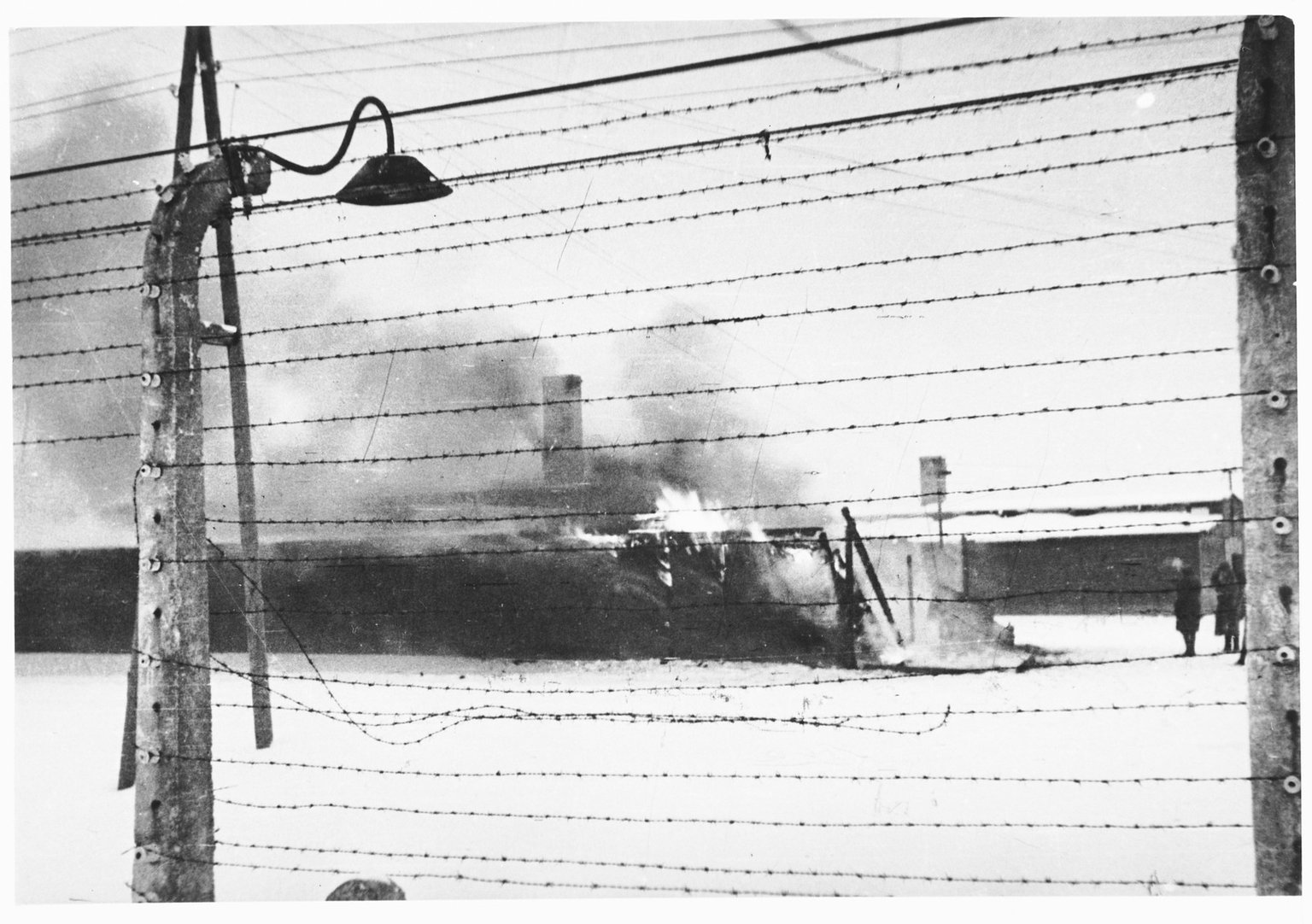

Jan. 27, 1945Auschwitz

Jan. 27, 1945AuschwitzAuschwitz is liberated: Otto Frank is free

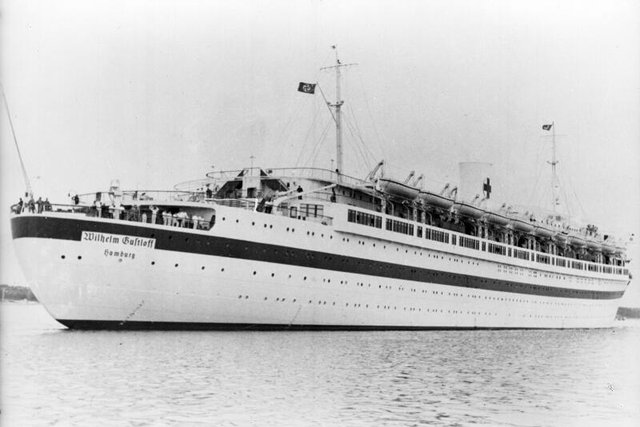

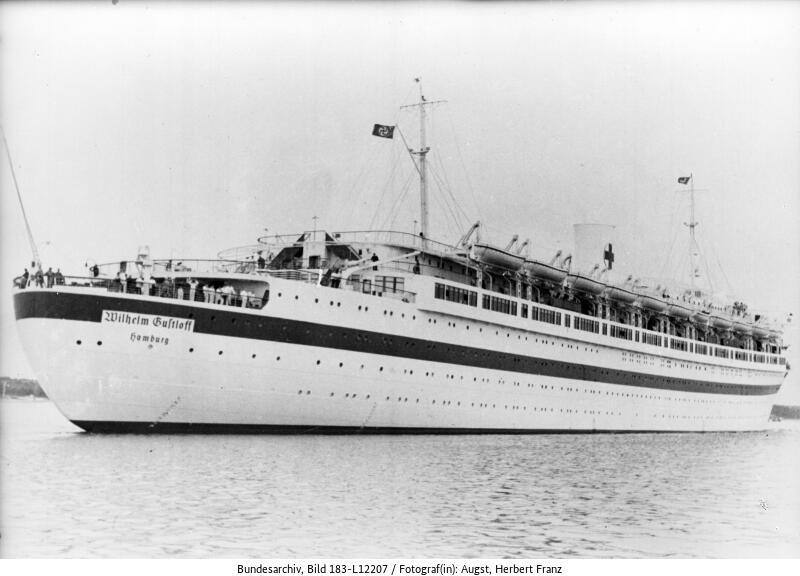

Jan. 30, 1945Gdynia, Oostzee

Jan. 30, 1945Gdynia, OostzeeThe Wilhelm Gustloff disaster

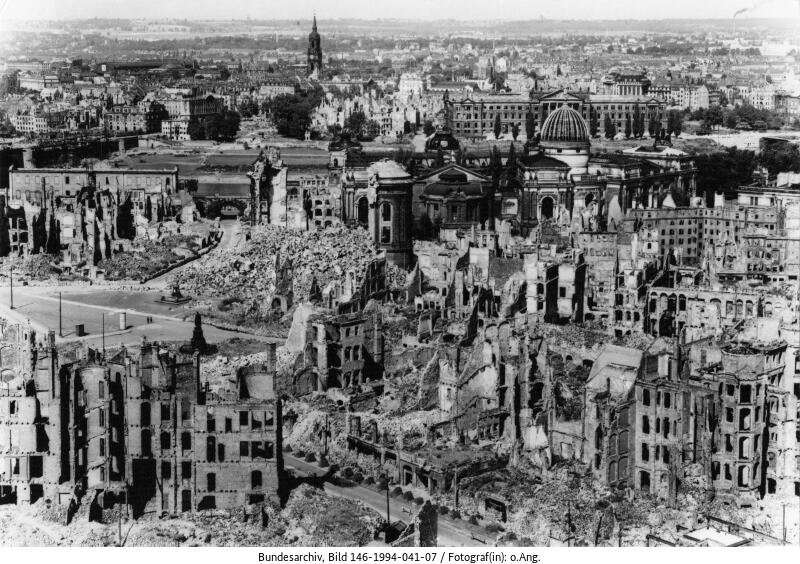

Feb. 13, 1945Dresden

Feb. 13, 1945DresdenDresden is destroyed

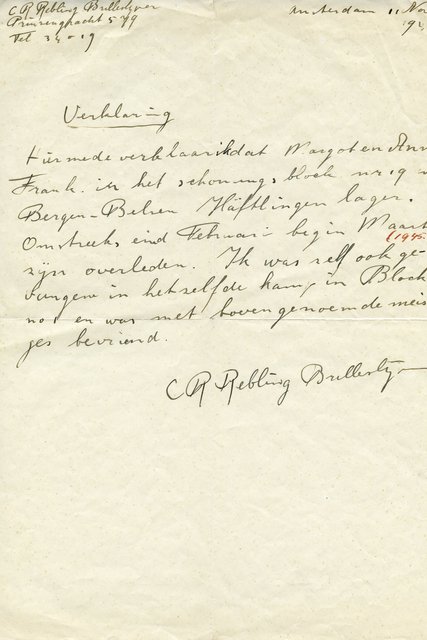

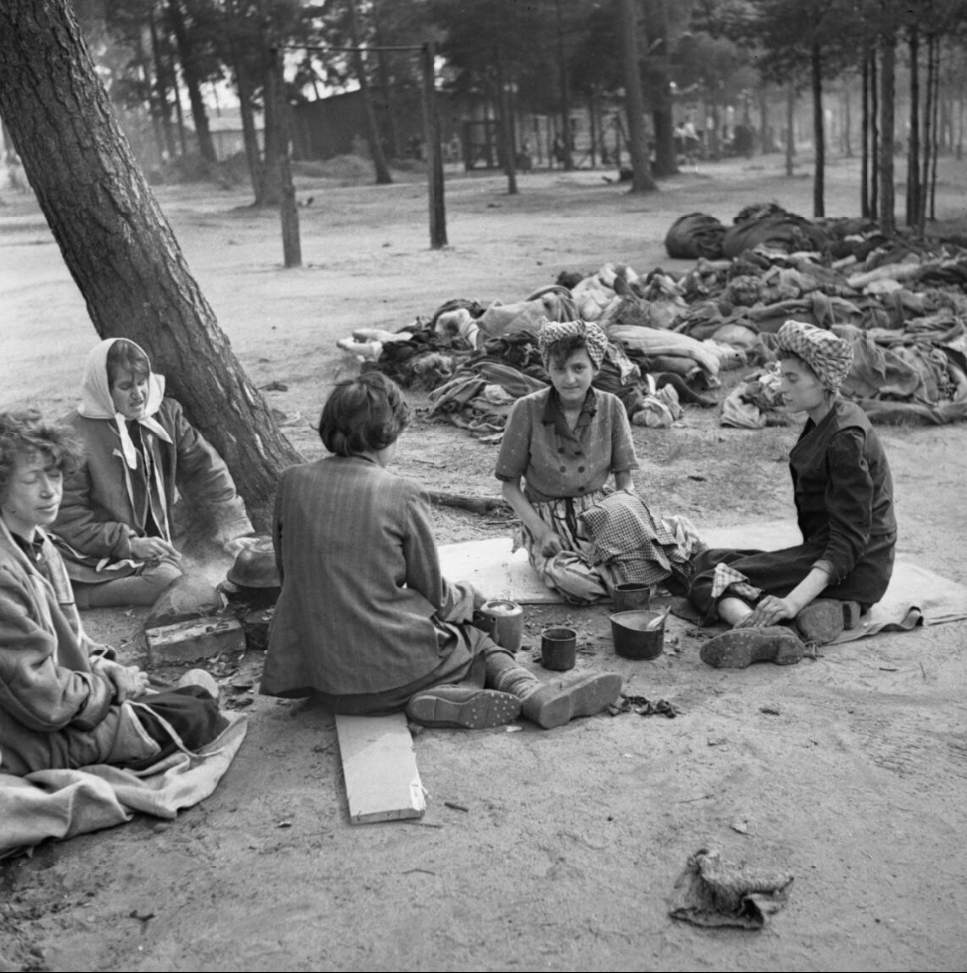

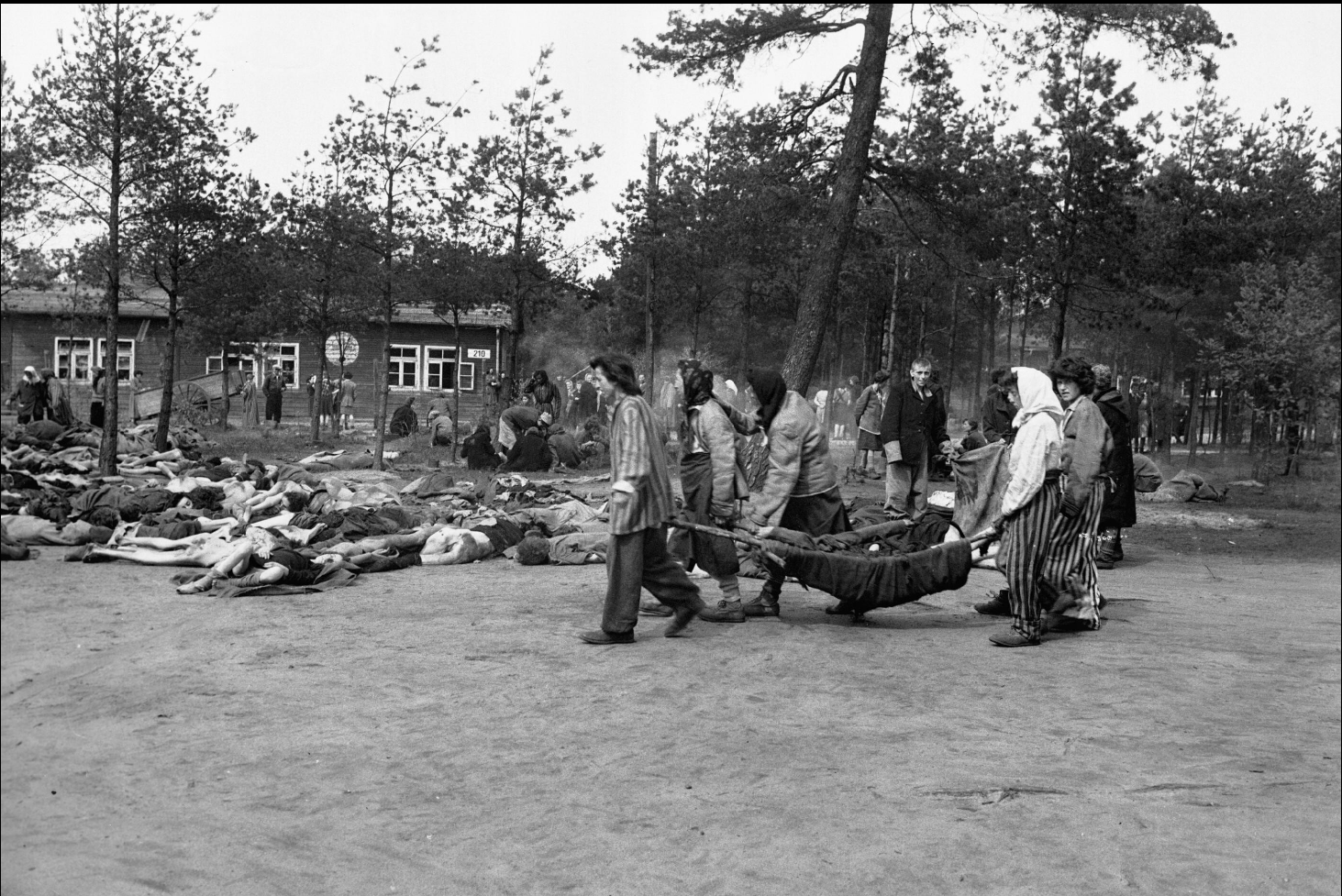

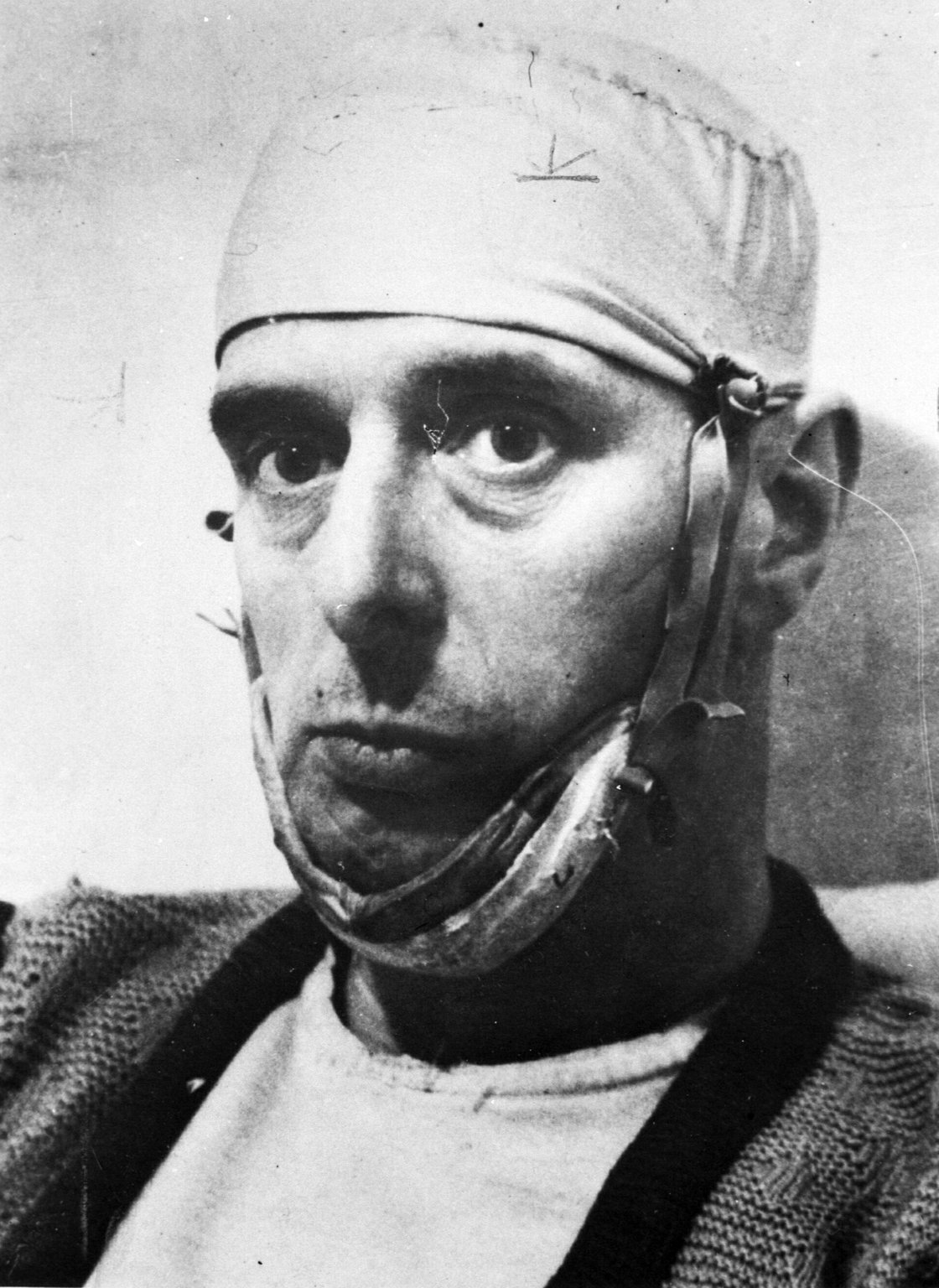

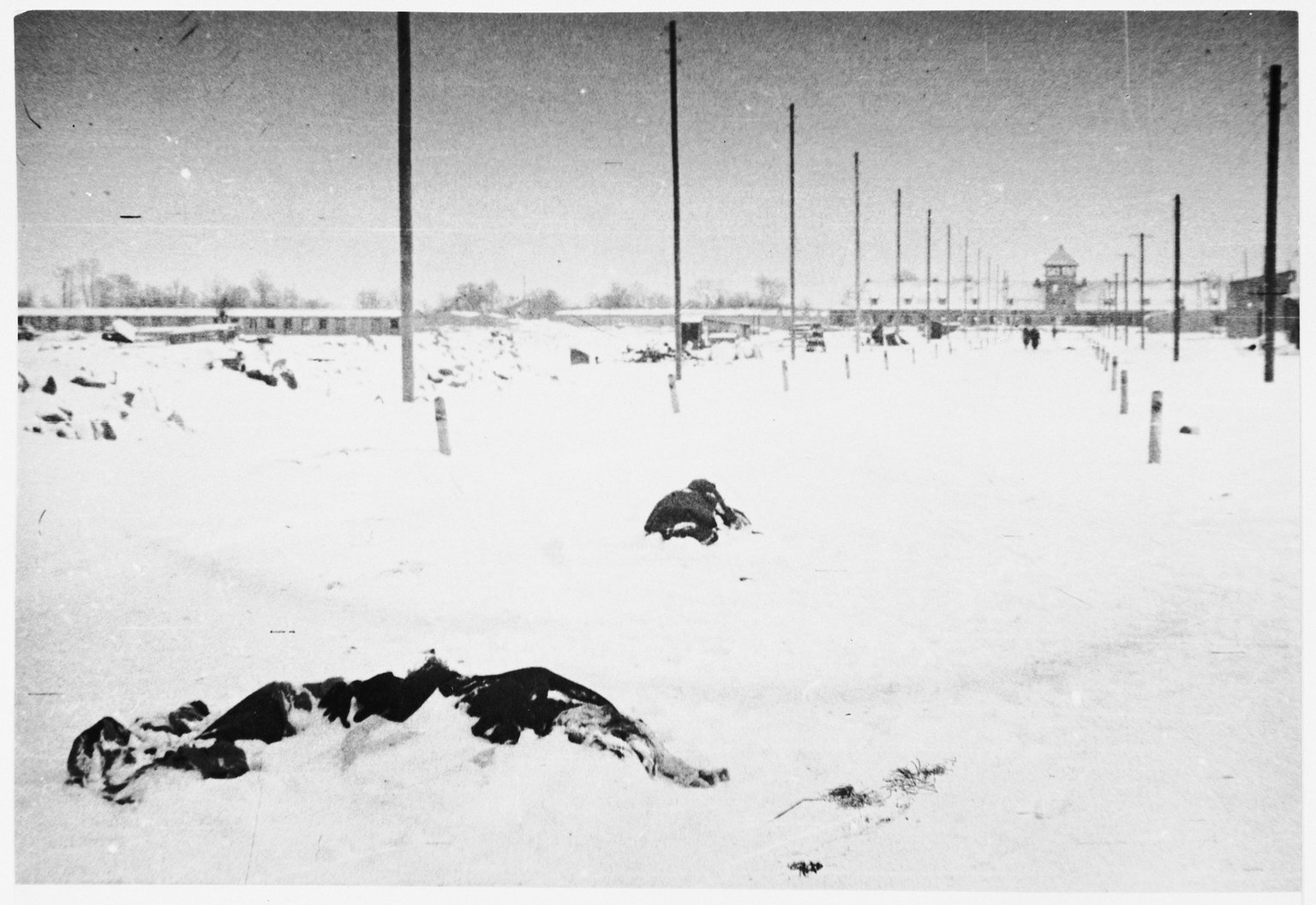

February 1945Bergen-Belsen

February 1945Bergen-BelsenAnne and Margot die exhausted in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

March 5, 1945Katowice

March 5, 1945KatowiceOtto travels back home

April 12, 1945Westerbork

April 12, 1945WesterborkWesterbork transit camp is liberated

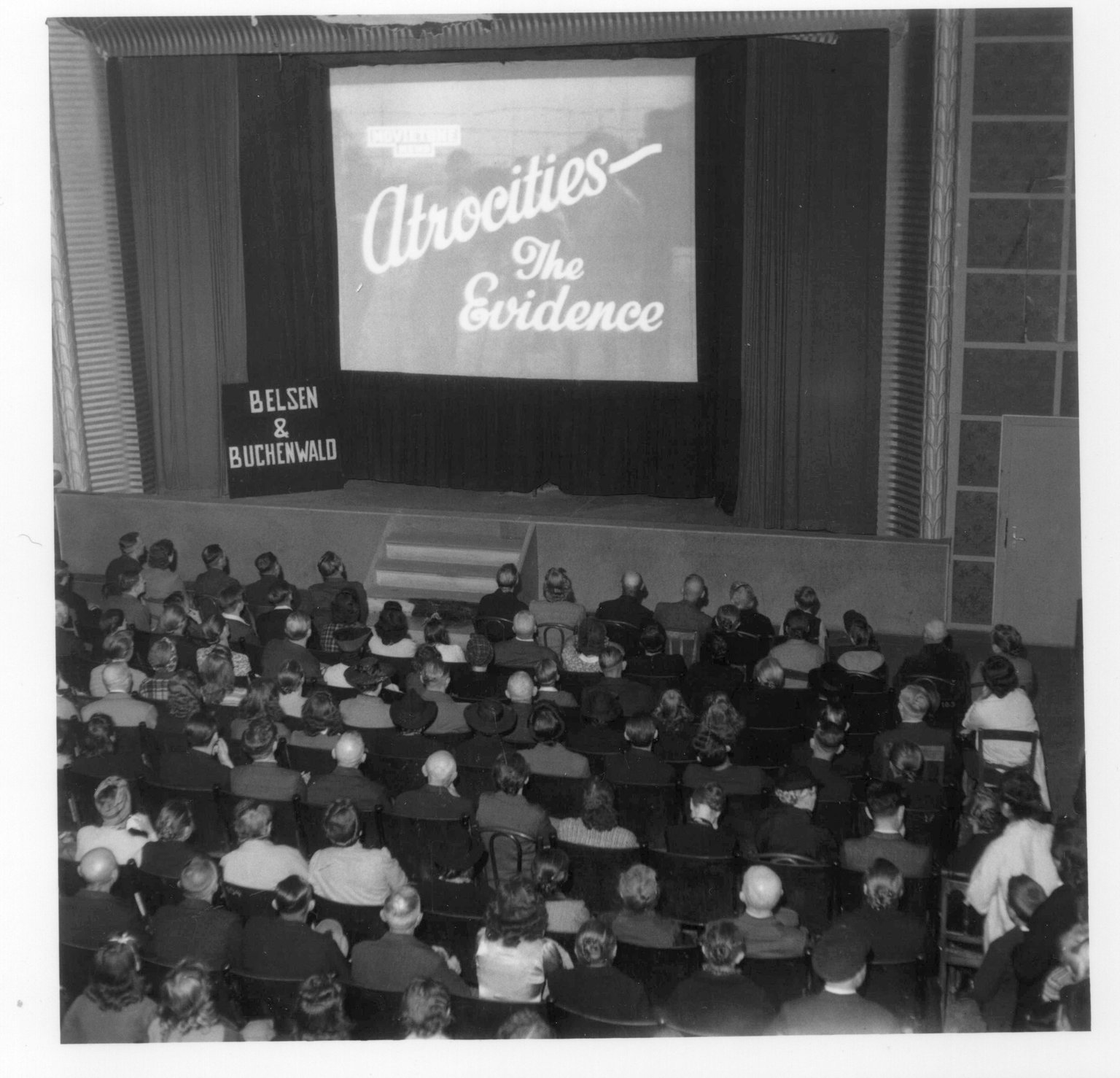

April 15, 1945Bergen-Belsen

April 15, 1945Bergen-BelsenThe liberation of Bergen-Belsen

April 30, 1945Berlin

April 30, 1945BerlinHitler dies

May 2, 1945Berlin

May 2, 1945BerlinThe Red Army conquers Berlin

May 5, 1945Amsterdam

May 5, 1945AmsterdamCommemoration of victims of public executions

May 5, 1945Wageningen

May 5, 1945WageningenGermany surrenders: The Netherlands is liberated

May 7, 1945The Hague

May 7, 1945The HagueArrest of NSB leader Anton Mussert

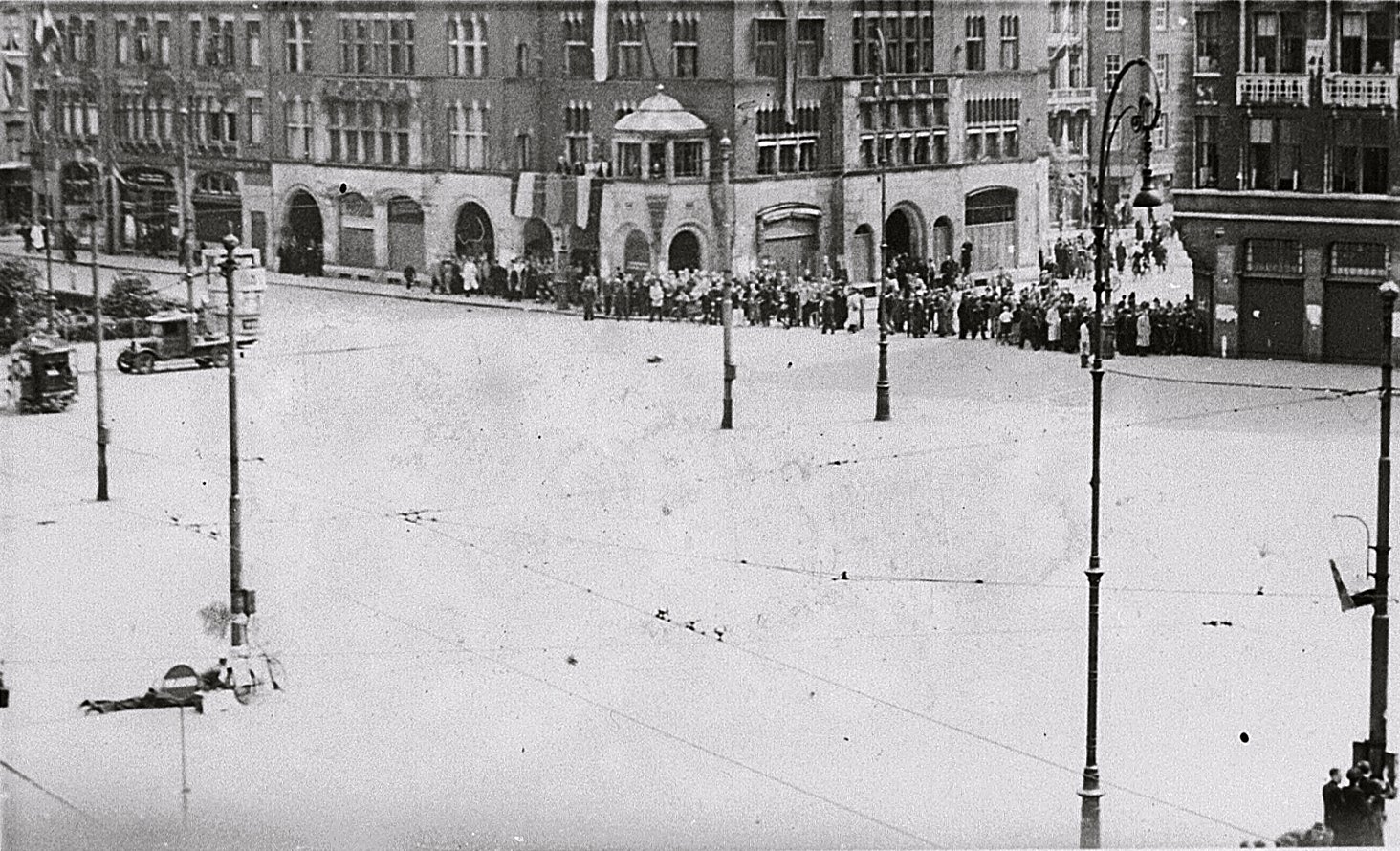

May 7, 1945Amsterdam

May 7, 1945AmsterdamShooting on Dam Square

May 7, 1945Reims

May 7, 1945ReimsGermany surrenders

May 1945The Netherlands

May 1945The NetherlandsLiberation festivities in the Netherlands

May 9, 1945The Netherlands

May 9, 1945The NetherlandsDay of Reckoning: the Dutch take revenge

May 9, 1945Amsterdam

May 9, 1945AmsterdamFirst synagogue service after the war

May 17, 1945Nammering

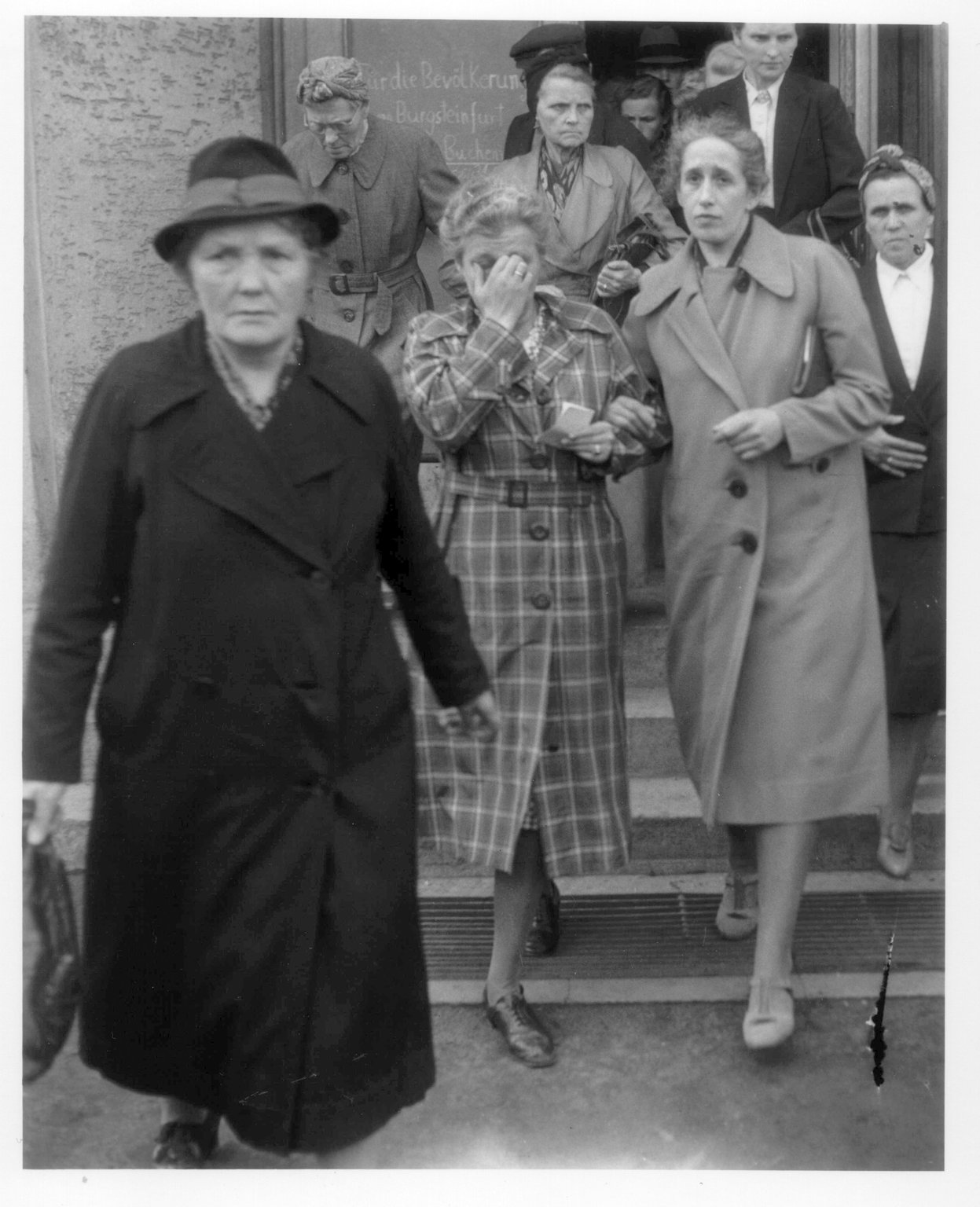

May 17, 1945NammeringGerman citizens see the consequences of war crimes

May 22, 1945Bremervörde, Germany

May 22, 1945Bremervörde, GermanyArrest and suicide of Heinrich Himmler

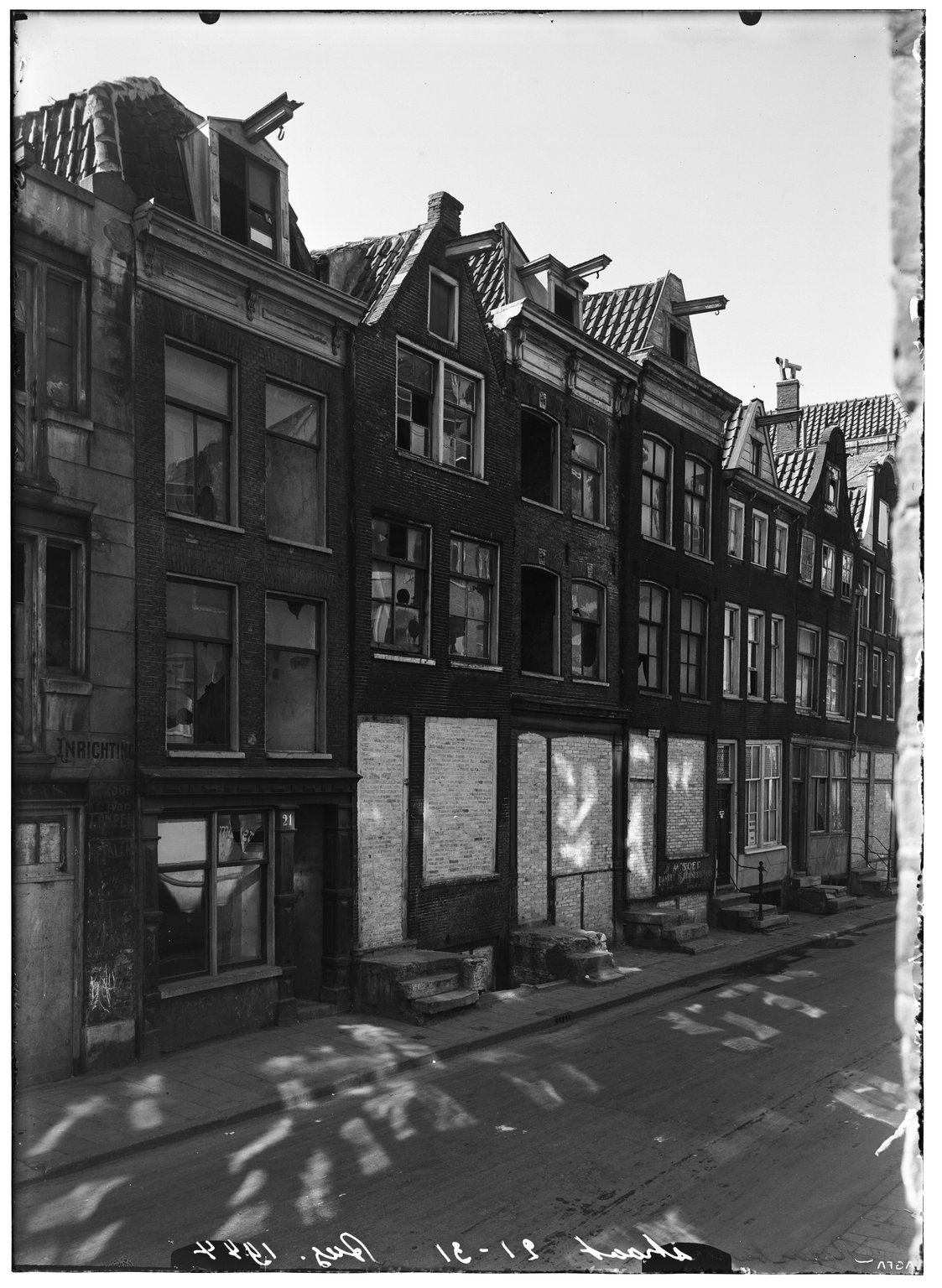

1945Amsterdam

1945AmsterdamEmpty Jewish houses

June 3, 1945Amsterdam

June 3, 1945AmsterdamOtto returns to Amsterdam

June 1945Amsterdam

June 1945AmsterdamSurvivors return from the concentration camps

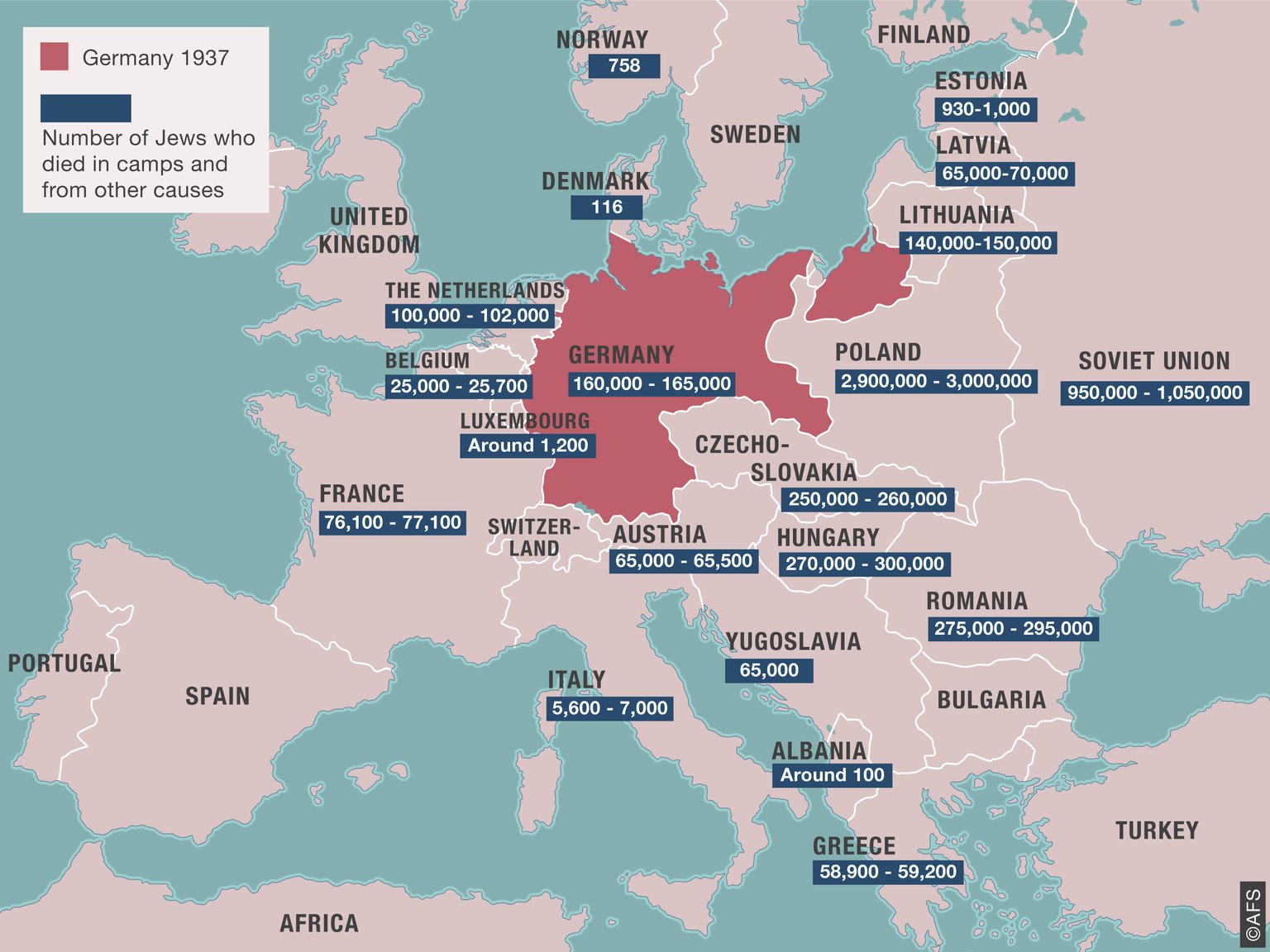

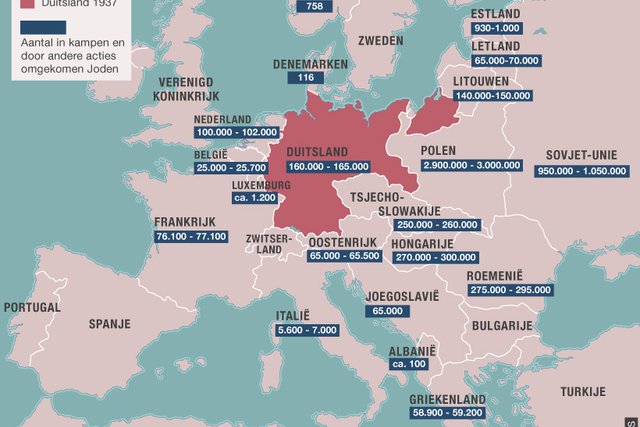

1945Europe

1945EuropeOverview of Holocaust victims by country

July 1945Amsterdam

July 1945AmsterdamOtto receives the diaries

July 17, 1945Potsdam

July 17, 1945PotsdamGermany is split up

August 1945Attichy, Frankrijk

August 1945Attichy, Frankrijk‘Baby Lager’

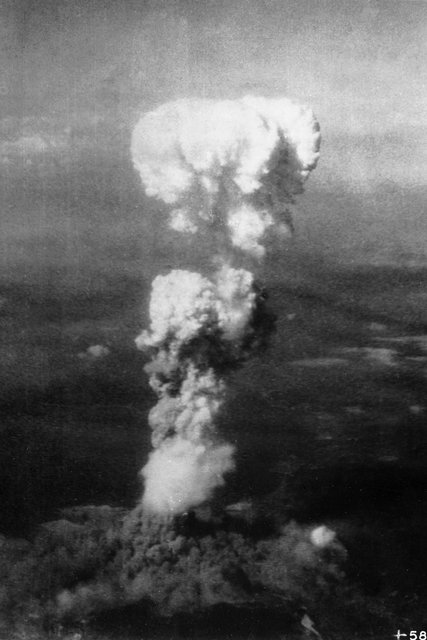

Aug. 6, 1945Hiroshima

Aug. 6, 1945HiroshimaThe United States drop atomic bombs on Japan

Sept. 17, 1945Lüneburg

Sept. 17, 1945LüneburgThe first Belsen trial

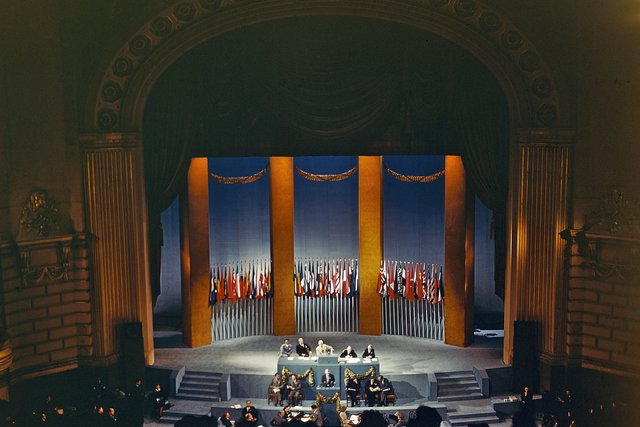

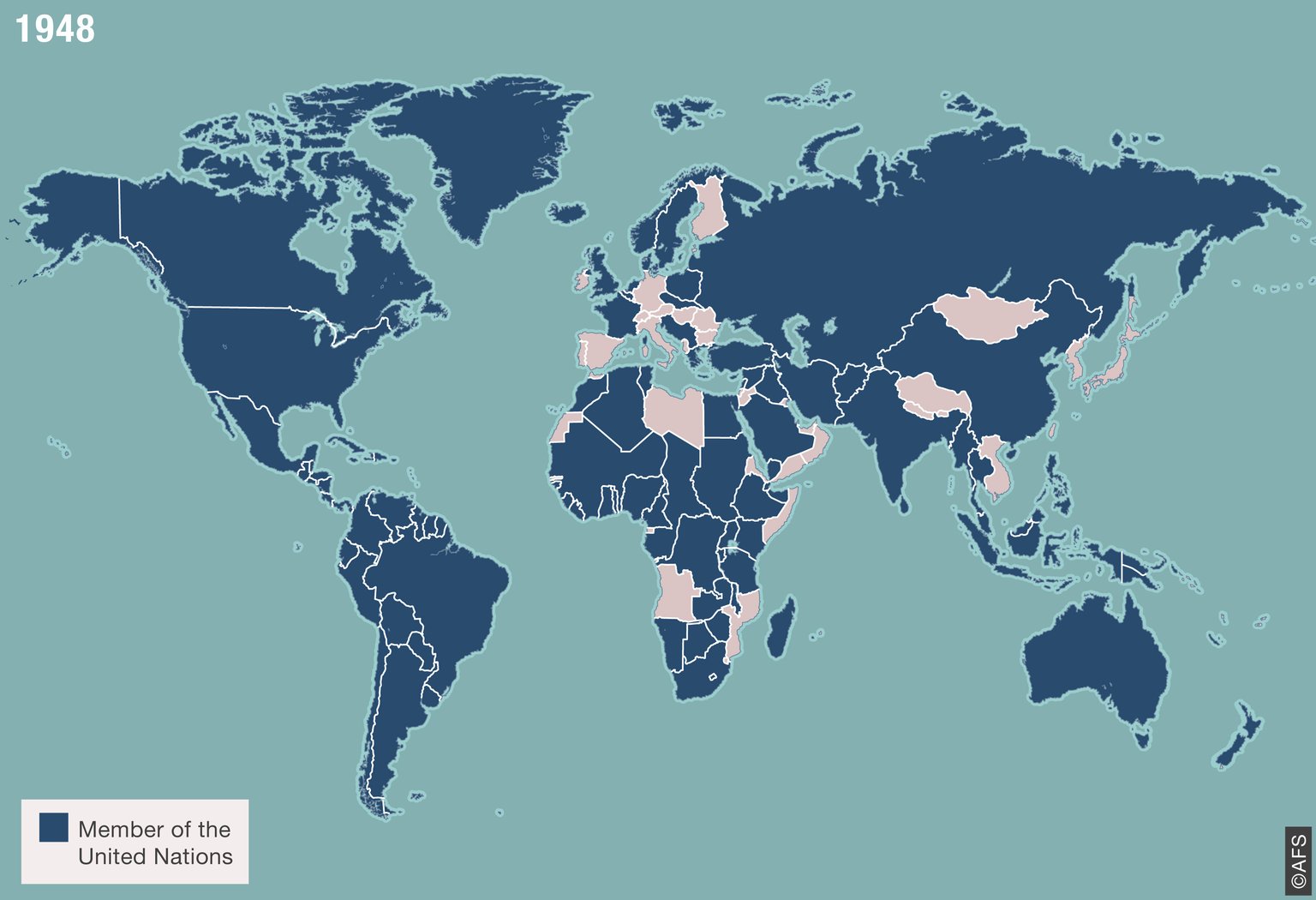

Oct. 24, 1945San Francisco

Oct. 24, 1945San FranciscoCreation of the United Nations

Nov. 20, 1945Nuremberg

Nov. 20, 1945NurembergNazi leaders on trial in Nuremberg

April 3, 1946Amsterdam

April 3, 1946AmsterdamArticle in the newspaper about the diary

April 16, 1946Bergen-Belsen

April 16, 1946Bergen-BelsenMonument to the Jewish victims at Bergen-Belsen

Feb. 25, 1947Waterlooplein, Amsterdam

Feb. 25, 1947Waterlooplein, AmsterdamCommemoration of the February Strike and persecuted Jews in Amsterdam

April 16, 1947Oświęcim

April 16, 1947OświęcimThe execution of Auschwitz Commander Rudolf Höss

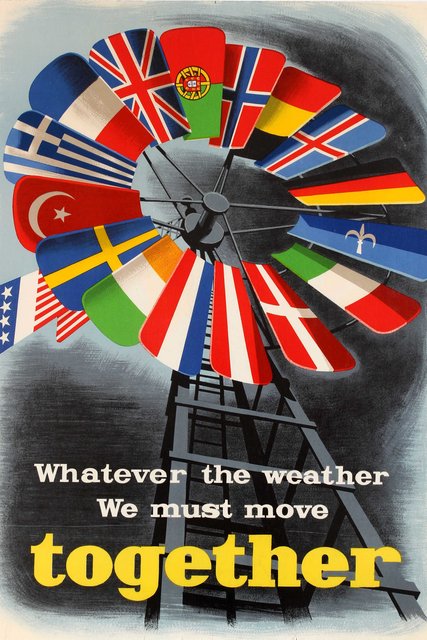

June 5, 1947Cambridge (Mass.), USA

June 5, 1947Cambridge (Mass.), USAThe Marshall Plan

June 14, 1947Oświęcim

June 14, 1947OświęcimAuschwitz becomes a museum and a memorial site

June 25, 1947Amsterdam

June 25, 1947AmsterdamAnne's wish comes true: ‘Het Achterhuis’ (‘The Secret Annexe’) is published

Dec. 13, 1947Amsterdam

Dec. 13, 1947AmsterdamThe National Monument on Dam Square

May 3, 1948The Hague

May 3, 1948The HagueRauter is sentenced to death

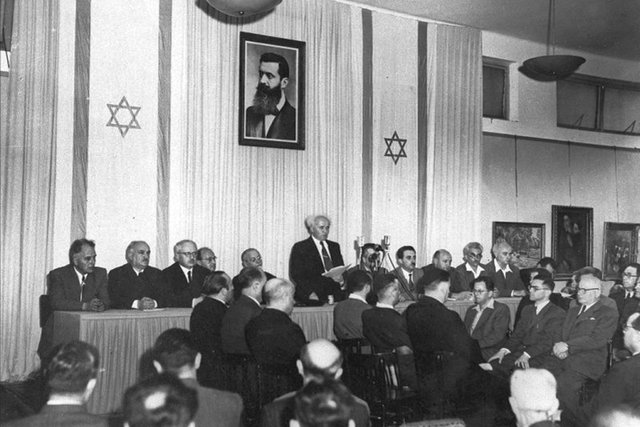

May 14, 1948Tel Aviv

May 14, 1948Tel AvivThe creation of Israel

Oct. 6, 1948Amsterdam

Oct. 6, 1948AmsterdamSS Negbah leaves for Israel

Dec. 9, 1948Paris

Dec. 9, 1948ParisThe United Nations adopts the Genocide Convention

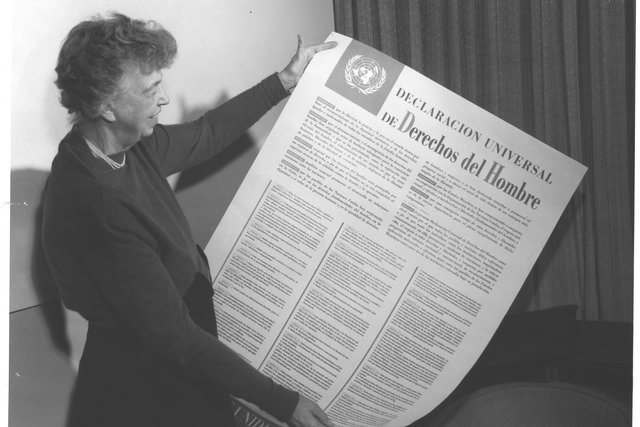

Dec. 10, 1948Paris

Dec. 10, 1948ParisThe UN adopts the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Dec. 19, 1952Amsterdam

Dec. 19, 1952AmsterdamTribute to the February Strike

May 15, 1953Rotterdam

May 15, 1953RotterdamUnveiling of ‘The Destroyed City’

July 29, 1954Jeruzalem

July 29, 1954JeruzalemFoundation of Yad Vashem

1955Amsterdam

1955AmsterdamJohannes Kleiman with visitors in the Secret Annex

1959Los Angeles

1959Los AngelesThe diary is turned into a Hollywood film

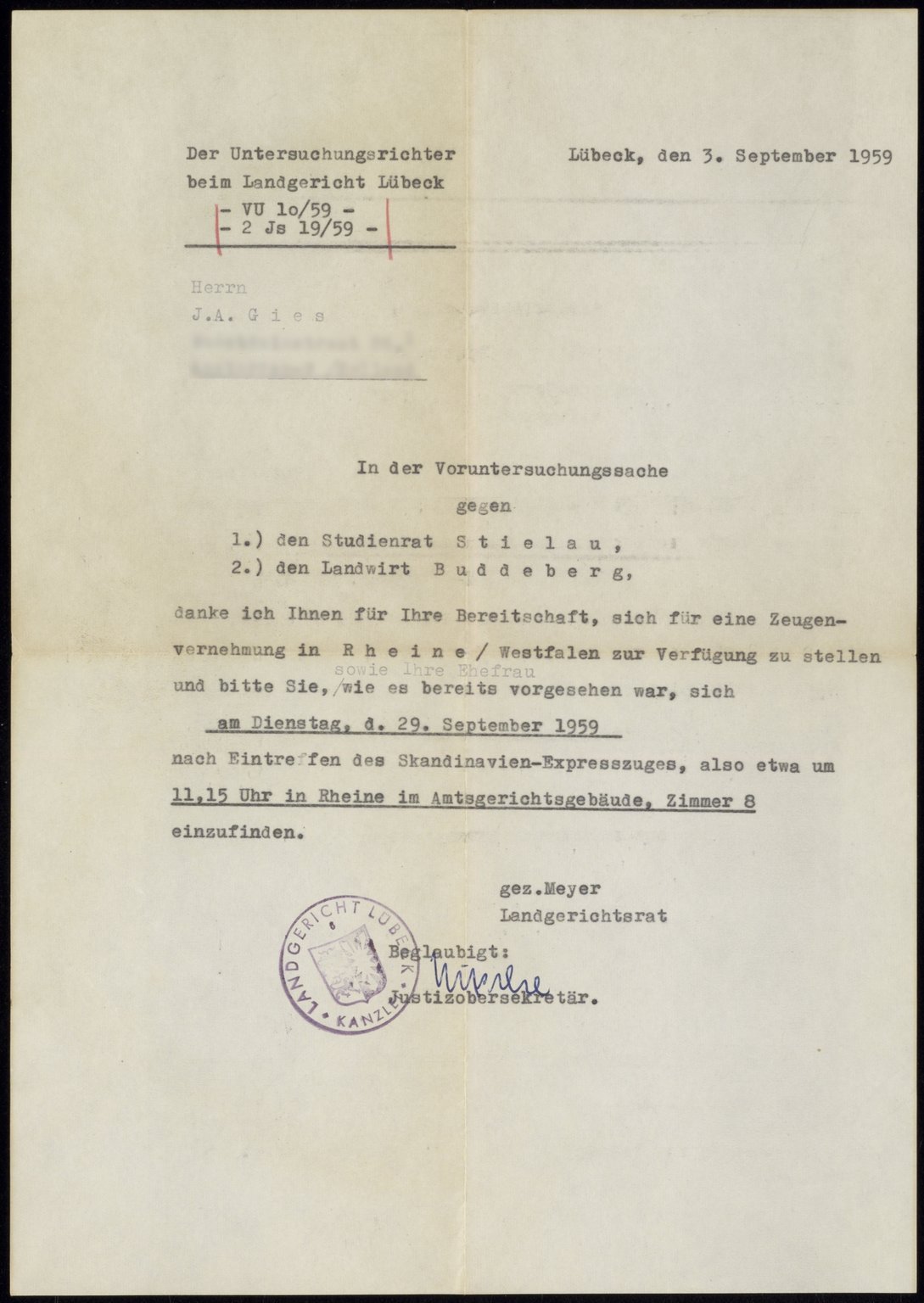

April 1959Lübeck

April 1959LübeckOtto Frank starts a lawsuit in defence of the diary

April 12, 1960Utrecht

April 12, 1960UtrechtPlacement of the statue of Anne Frank in Utrecht

May 3, 1960Amsterdam

May 3, 1960AmsterdamThe old hiding place becomes a museum: the Anne Frank House

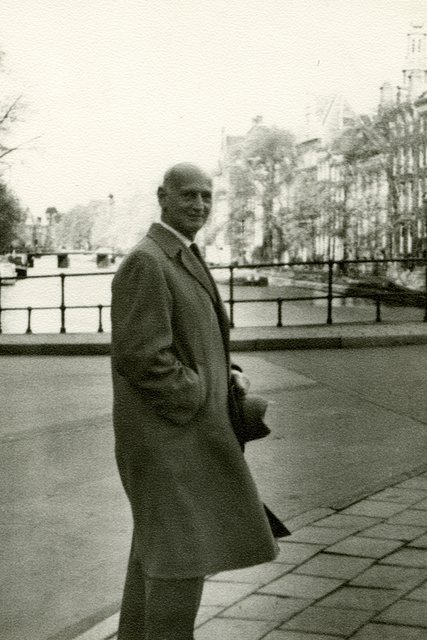

May 11, 1960Buenos Aires - Jerusalem

May 11, 1960Buenos Aires - JerusalemIsrael kidnaps Adolf Eichmann, architect of the Holocaust

May 3, 1961Amsterdam

May 3, 1961AmsterdamOpening International Youth Centre of the Anne Frank Stichting

1963Vienna

1963ViennaArrest and release of Karl Silberbauer

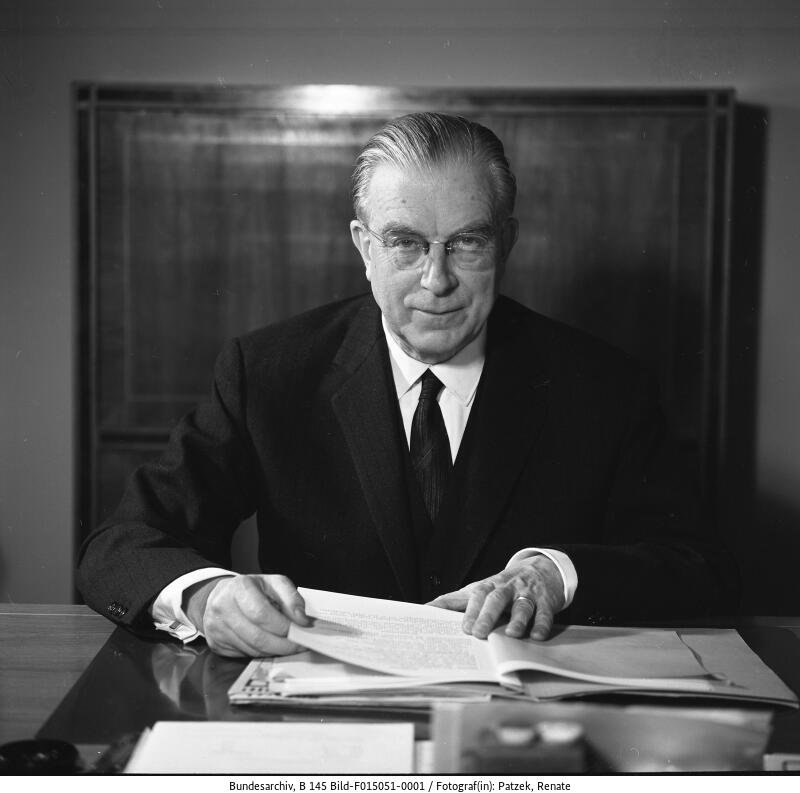

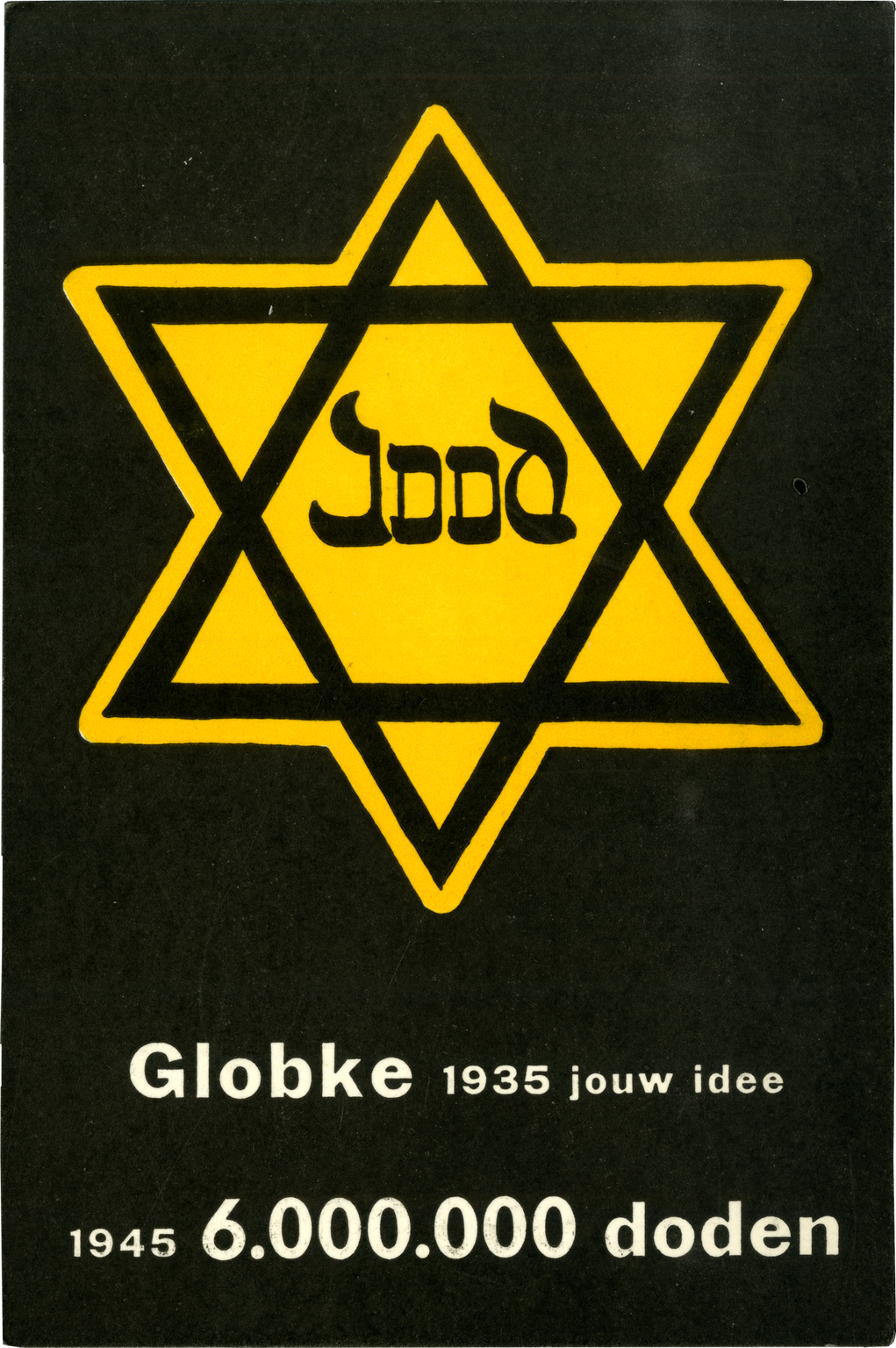

July 1, 1963East Berlin, GDR

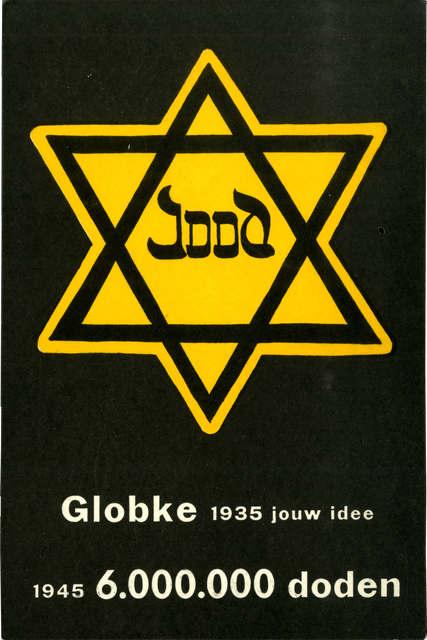

July 1, 1963East Berlin, GDRTrial of former Nazi Hans Globke

July 1968Amsterdam

July 1968AmsterdamOtto Frank at a youth conference at the Anne Frank House

Aug. 19, 1980Basel

Aug. 19, 1980BaselOtto dies

Murder of the Austrian Archduke: Start of the First World War

June 28, 1914 Sarajevo

In response, Austria-Hungary set Serbia an ultimatum. If Serbia failed to meet its demands, the Austro-Hungarian army was going to invade Serbia. The Serbs accepted all demands, except one. They wanted to investigate the murder themselves, without interference from the Austro-Hungarian representatives. Austria-Hungary did not agree and on 28 July 1914 declared war on Serbia.

The fact that this crisis resulted in a world war was due in part to the alliances between the various European countries. As many states were bound by treaties to help one another in the event of war, there were two camps: the Central Powers (Austria-Hungary and Germany) and the Allied Powers (France, Russia and England).

Both sides expected the war to be over soon, but they were wrong. The First World War lasted four years, and millions of soldiers from all over the world were killed.

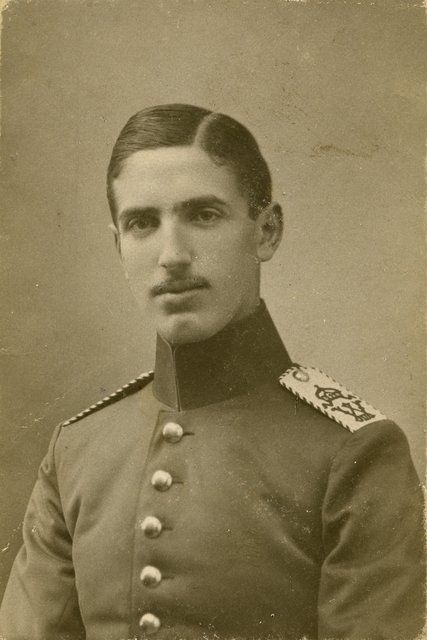

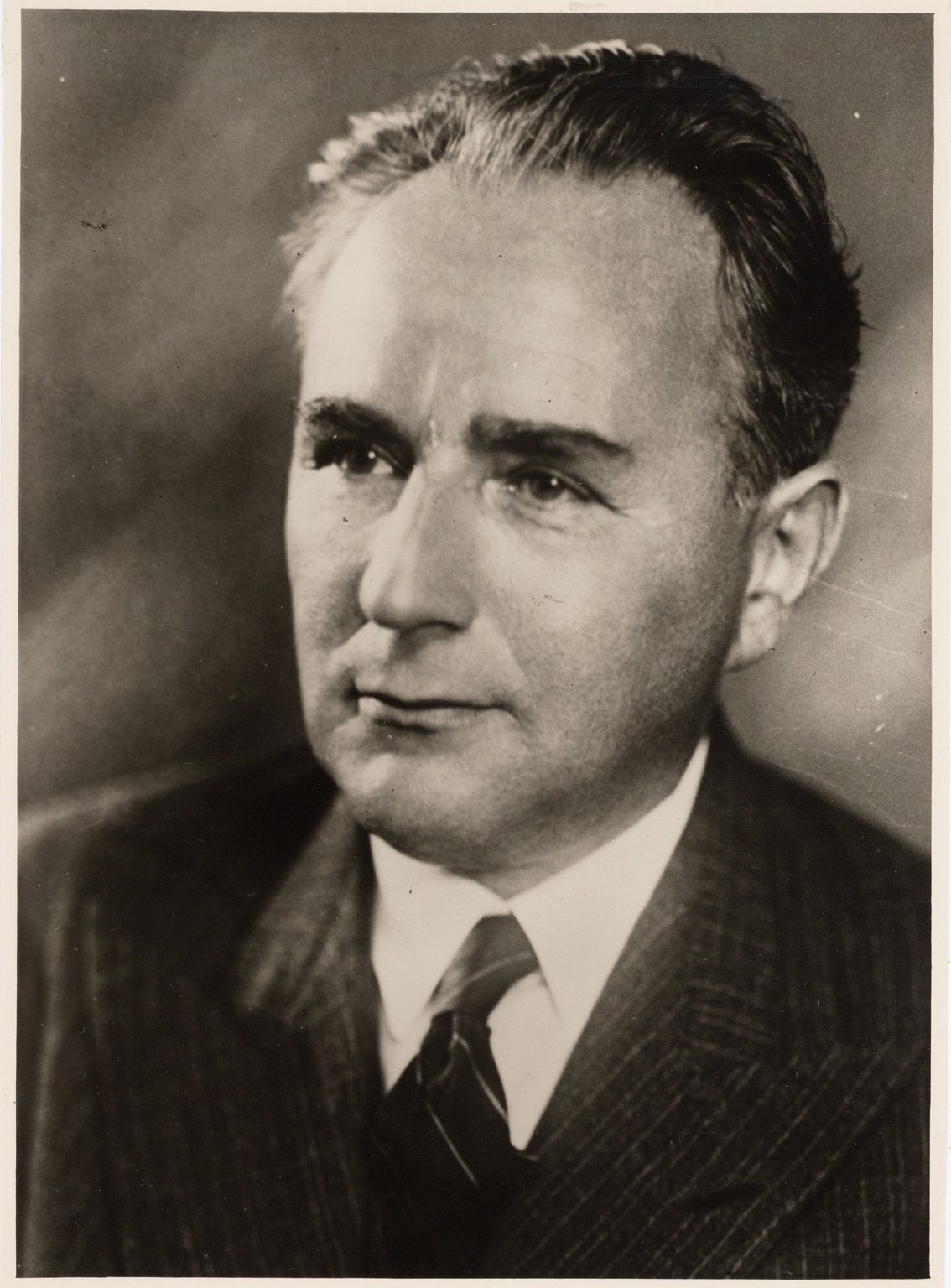

Otto Frank in the First World War

Aug. 6, 1915 Germany

In August 1915, Otto Frank went into the German army. He was trained as a gunner. From the autumn of 1915 onwards, he was stationed at the Western Front. He was part of a so-called Lichtmesstrupp: a unit that detected and calculated the location of enemy guns and passed information about the trajectory on to the artillery.

In 1916, he took part in the Battle of the Somme, in which almost half a million German soldiers were killed. A year later, Otto was promoted to sergeant and the year after that to officer candidate.

Otto's brothers Herbert and Robert served in the German army as well. Their mother Alice Frank-Stern and sister Leni Frank were nurses in a military hospital.

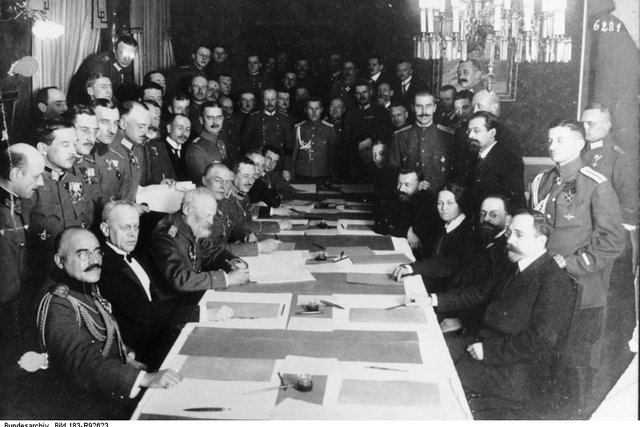

The Russian Revolution: Armistice with Germany

Nov. 7, 1917 Petrograd (Saint Petersburg)

In early 1917, the situation in Russia was turbulent. The people were hungry and tired of war. In March, Czar Nicolas II abdicated after days of protest. Eight months later, the communists staged a coup under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. This event is known as the October Revolution. The communists were supported by part of the population because of their slogan "peace, land, and bread". The Provisional Government was overthrown.

In order to fulfil their promise of peace, the communists had to stop fighting Germany. In December 1917, Lenin sent his closest collaborator, Leon Trotsky, to Brest-Litovsk (in modern-day Belarus) to negotiate with the Germans. On 3 March 1918, the German delegation agreed to a ceasefire in exchange for large areas of Russian territory. The Germans no longer had to fight on two fronts, but many German troops still stayed behind in the east because the situation there remained turbulent.

Germany loses the war: Protests against the Treaty of Versailles

May 15, 1919 Berlin

When the First World War ended in 1918, peace negotiations began in Paris. Germany was considered mainly to blame for the devastating war. The conclusions were laid down in the Treaty of Versailles, named after the palace where the countries signed the treaty.

The Treaty of Versailles caused furious reactions in Germany. Germany had to pay huge sums of money to the countries it had fought in compensation for the damage. In addition, France, England, and the United States wanted to prevent Germany from becoming strong enough to start a new war. They allowed Germany to keep only a small army.

In addition, Germany had to cede parts of its territory. France gained Alsace-Lorraine and the coal mines in the Saar region. Germany was allowed to keep the Rhineland, but without an army. The German government in the Rhineland was replaced by a government made up by Great Britain and France - Germany’s old enemies. In the east, Germany lost another part of its territory. This became part of Poland, which also gained land from Russia and Austria-Hungary. Finally, Germany lost its colonies in Africa and Asia.

The Germans felt that they should not have been blamed for the war. The loss of territory was considered extremely humiliating. Moreover, the sky-high reparations caused great poverty throughout the country.

Poverty and hunger in Vienna: Miep Gies comes to the Netherlands

Dec. 1, 1920 Vienna

In December 1920, Miep Gies came to The Netherlands. Her birth name was Hermine Santrouschitz and she came here from Vienna, the capital of Austria. She was 11 years old when her parents sent her to the Netherlands to recover from tuberculosis and malnutrition. She was taken in by a foster family in Leiden. She felt very much at home and with the consent of her biological parents, she stayed on in the Netherlands.

Austria came into being after the Austrian-Hungarian Empire fell apart at the end of the First World War. It took a lot of effort to overcome the hardships of the war. When there was a famine in Vienna, foster families in England, France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands took in hungry and sick children. The people who stayed behind received help from American aid organisations.

The NSDAP party programme

Feb. 24, 1924 Munich

The Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) was founded in 1920. It was the continuation of the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (DAP), but Hitler had its name changed. The programme consisted of a list of 25 points. A few important points:

- The good of the community before the good of the individual

- The Treaty of Versailles must be repealed

- There must be a central and strong power of the state

- More land is needed for population growth

- Criminals must be sentenced to death

- Some residents of Germany cannot be citizens and only citizens have equal rights

The programme contained many antisemitic points:

- According to the Nazis, Jews do not belong to the German people because they ‘have no German blood’. That is why they are not citizens

- Since Jews are not citizens, they are ‘guests’ in Germany. Different laws apply to ‘guests’

- Jews may not be civil servants because they are not citizens

- Should the German government ever be unable to take care of its citizens, the ‘guests’, such as the Jews, will be expelled from the country.

- Residents of other countries who are not citizens are no longer allowed to enter Germany. All non-German immigrants who have come to the country after 1914, will be made to leave

- Only members of the 'German race' can be journalists, publishers or owners of newspapers. So, Jews cannot

- The Jewish faith is suppressed

This party programme remained in force for as long as the Party existed.

Adolf Hitler publishes ‘Mein Kampf’

July 18, 1925 Munich

On 18 July 1925, Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf (‘My Struggle’) was published. He wrote it in prison, where he was serving a sentence for a failed coup he attempted in 1923.

In Mein Kampf, Hitler wrote about his ideology and presented himself as the leader of the extreme right. He talked about his life and his youth, his 'conversion' to antisemitism (the hatred of Jews) and his time as a soldier in the First World War.

He raged against the Treaty of Versailles and the reparations that Germany had to pay because of the Treaty. He did not believe in parliamentary democracy. Mein Kampf is full of racist ideas and hatred of Jews and communists.

In Mein Kampf, Hitler also wrote a lot about the future of Germany. He wanted to expand the German territory in Eastern Europe and to throw the Jews out of Germany, since he believed they threatened the survival of the German people. Although Mein Kampf does not refer to the later mass murder of Jews during the Second World War (the Holocaust), it does show that he had already developed a hatred of Jews at this time.

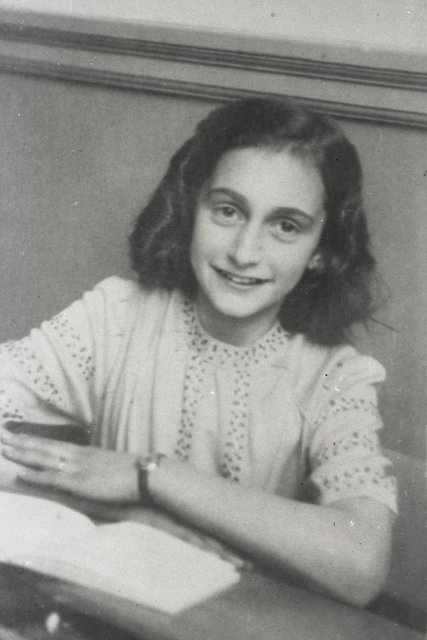

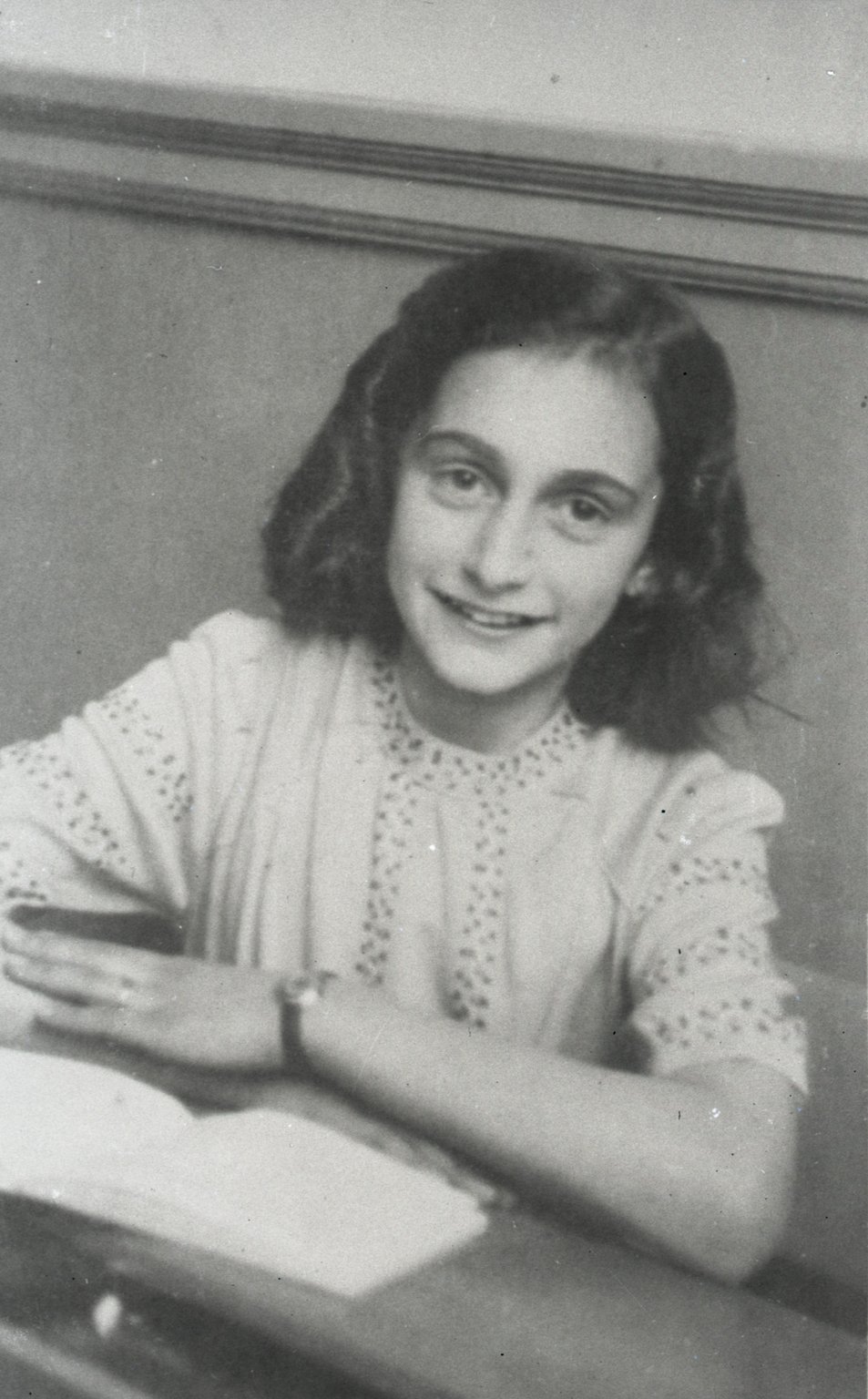

Anne Frank is born

June 12, 1929 Frankfurt

Anne Frank was born on 12 June 1929 in Frankfurt, at the Maingau Red Cross Hospital. She weighed over 8 pounds and was 54 cm long. Margot was taken to see her the next day and very happy with the arrival of her baby sister. Ten days later, Anne and her mother Edith were allowed to go home.

Until March 1931, Anne and her family lived at Marbachweg 307 in Frankfurt am Main. It was a pleasant time for Anne and Margot. It was a neighbourhood with lots of children and almost every day, friends came over to play with Margot. Anne could often be found in the sandbox in the garden. She was still too young to be allowed out of the garden. Margot was allowed to leave the garden, though, and she often played in the street with her friends.

Hitler and the Nazis come to power in Germany

Jan. 30, 1933 Berlin

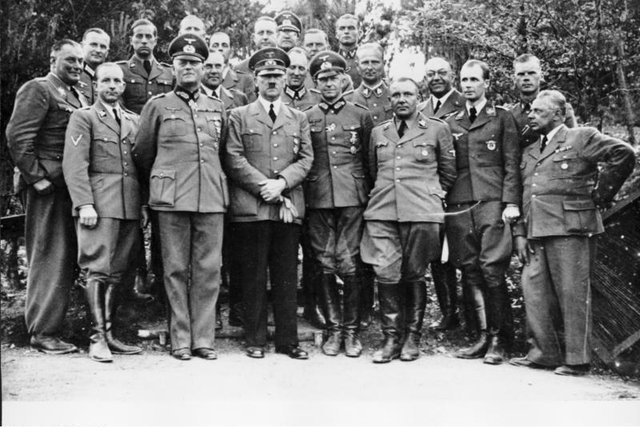

On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor, leader of the German government. The Nazis’ desire for power was fulfilled. ‘It is like a dream. The Wilhelmstraße (the street where the Chancellery is located) is ours’, Joseph Goebbels, the future Minister of Propaganda, wrote in his diary.

That same evening, the Nazis held a torchlight procession through Berlin. Uniformed members of the SA (Sturmabteilung - Nazi fighters) marched under the Brandenburg Gate and past the new address of their leader. Despite the impressive propaganda images Goebbels would produce later, not all Germans were impressed. Many of them did not expect Hitler to last very long at all.

After his appointment, Hitler was still no autocrat. His new cabinet contained only two members of his own party, the NSDAP. The other ministers came from other right-wing parties. Nonetheless, Hitler managed to get his people appointed to important positions. Wilhelm Frick was appointed Minister of the Interior, and Hermann Göring took control of Prussia's police force. As a result, Hitler became relatively powerful in Germany.

Anne Frank emigrates to Amsterdam: a new life in a new city

Feb. 16, 1934 Amsterdam

Anne Frank came to Amsterdam in February 1934. Her father Otto had been living there for over six months. He had left Germany for the Netherlands in July 1933 to set up his company Opekta. Edith joined him in September and started looking for a house. Meanwhile, Anne and her sister Margot stayed with their grandmother in Aachen.

Margot came to Amsterdam in December and Anne followed in February. Margot started school in January and Anne in April. She learned Dutch quickly and had no trouble making new friends.

Otto about Anne: ‘As soon as she entered the living room, things got turbulent, especially since she often took a whole bunch of friends home. She was very popular because she always had ideas about the games they could play or the things they could get up to.'

Hitler’s first military action: German troops occupy the Rhineland

March 7, 1936 Germany

In the morning of 7 March 1936, German troops occupied the Rhineland, a part of Germany that bordered on France. According to the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was not allowed to station an army there.

Hitler took a big risk, as he did not know how the Allies would react. He only deployed 3,000 soldiers. He had police officers march along to increase the visual impact. They had all been ordered to withdraw if foreign countries were to intervene.

But nothing happened. Other countries took hardly any countermeasures. Germany's old enemies, France and England, were busy dealing with domestic problems of their own and did not want to get involved in another war. Others felt that Germany was entitled to reclaim the Rhineland. The area had always been German until after the First World War, and Hitler's predecessors had wanted it back as well.

The gamble paid off for Hitler. It encouraged him to try to break other international agreements with impunity. Moreover, by occupying the Rhineland, he had also taken away France’s strategic advantage, and that would come in handy in a new war. He was now able to reposition his troops along the French border. In Germany, his popularity was growing because he had erased the 'disgrace' of the Treaty of Versailles. Once again, Germany was a force to be reckoned with.

The Kristallnacht proves that Jews have no future in Germany

Nov. 9, 1938 Germany

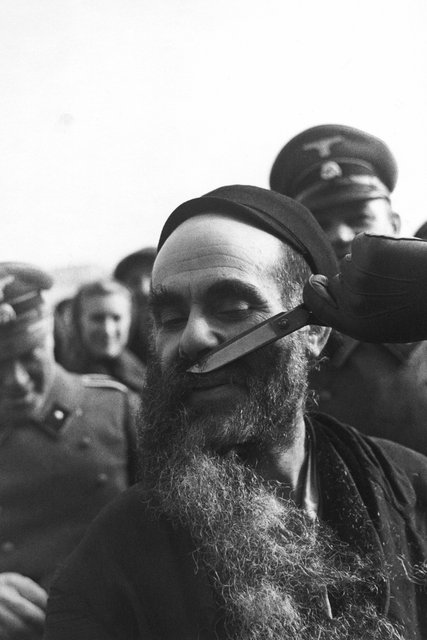

On 9 and 10 November 1938, Nazis throughout Germany, Austria, and Sudetenland (in the current Czech Republic) took action against Jews. They humiliated Jews in parades, abused them and put them in concentration camps. They also destroyed Jewish property. Such violent attacks on Jews are called pogroms.

Because of the many broken windows, this particular pogrom is called the Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. Synagogues were set on fire and the fire department was not allowed to put the fires out. The Jews had to pay for the damage themselves and were fined a total of 1 billion Reichsmark by the government.

The immediate cause of the Kristallnacht was the murder of a German diplomat in Paris by Herschel Grynszpan. It was his way to avenge the ill-treatment of his family, Polish Jews who had been living in Germany for 27 years and who had recently been deported to Poland by the Gestapo (the secret German police).

The Kristallnacht showed how the Nazi hatred of the Jews had turned into aggression and persecution - and how hardly anyone stood up for the Jews.

Fritz Pfeffer flees Germany for the Netherlands

Dec. 9, 1938 Amsterdam

Fritz Pfeffer was a dentist in Berlin. He was engaged to Charlotte Kaletta, who was a Roman Catholic. He could not marry her, because the German racial laws prohibited marriages between Jews and non-Jews.

In November 1938, Jews were assaulted and arrested throughout Germany during the so-called Kristallnacht. Synagogues were set on fire, and shops and other Jewish properties were destroyed. For Fritz, the time had come to leave Germany. On 1 December, he put his young son Werner on a ship to his brother in England. Fritz himself fled to the Netherlands. He was joined by Charlotte three weeks later.

The couple could not marry in the Netherlands either, because the Netherlands observed the German law in this respect because of an old treaty. Fritz wanted to marry in Belgium, but he could not go there because his passport had expired. Eventually, he hoped to go to Chile to work as a horse breeder, as he was a great lover of horses. These plans, too, failed due to the war.

In 1942, Fritz went into hiding in the Secret Annex, where he shared a room with Anne Frank.

The start of the Second World War: Germany invades Poland

Sept. 1, 1939 Poland

On the morning of 1 September 1939, Hitler's voice was heard on the radio. He claimed that Germany had been attacked by Poland and that they had ‘started to fire back at 5:45 am’. However, his story about the Polish attack was a lie. German soldiers, dressed as Poles, had attacked a radio station in the border town of Gleiwitz and spread false information. It gave Hitler an excuse to attack Poland.

The German army used a lot of violence. The Air Force in particular caused a lot of damage. Heavy bombings reduced the Polish capital Warsaw to ruins. Tens of thousands of soldiers were killed. England and France had promised to help Poland in the event of a German attack, and so they declared war on Germany. The Second World War had begun.

Hitler had attacked Poland because he wanted Germans to live there. He considered the Polish people inferior and only fit as a work force. In the last three months of 1939, the Nazis murdered 65,000 Jewish and non-Jewish Poles.

While Poland was defending itself against Germany in the west, on 17 September, the Soviet Union attacked the country from the east. This two-pronged attack was too much for Poland. On 6 October 1939, its last troops surrendered.

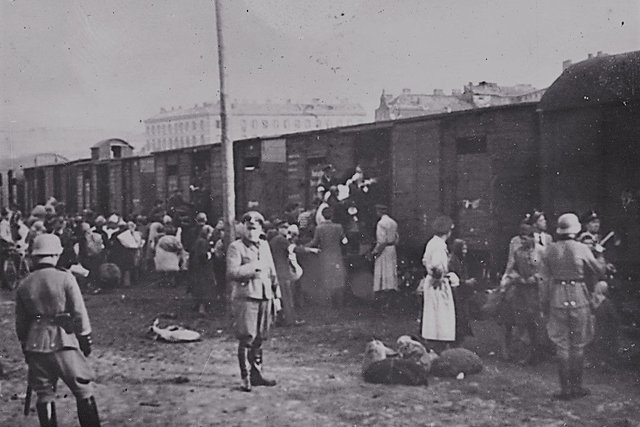

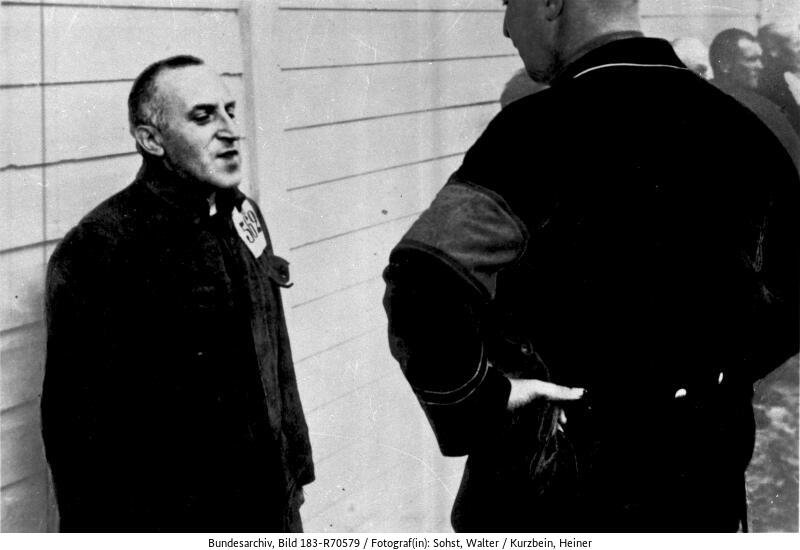

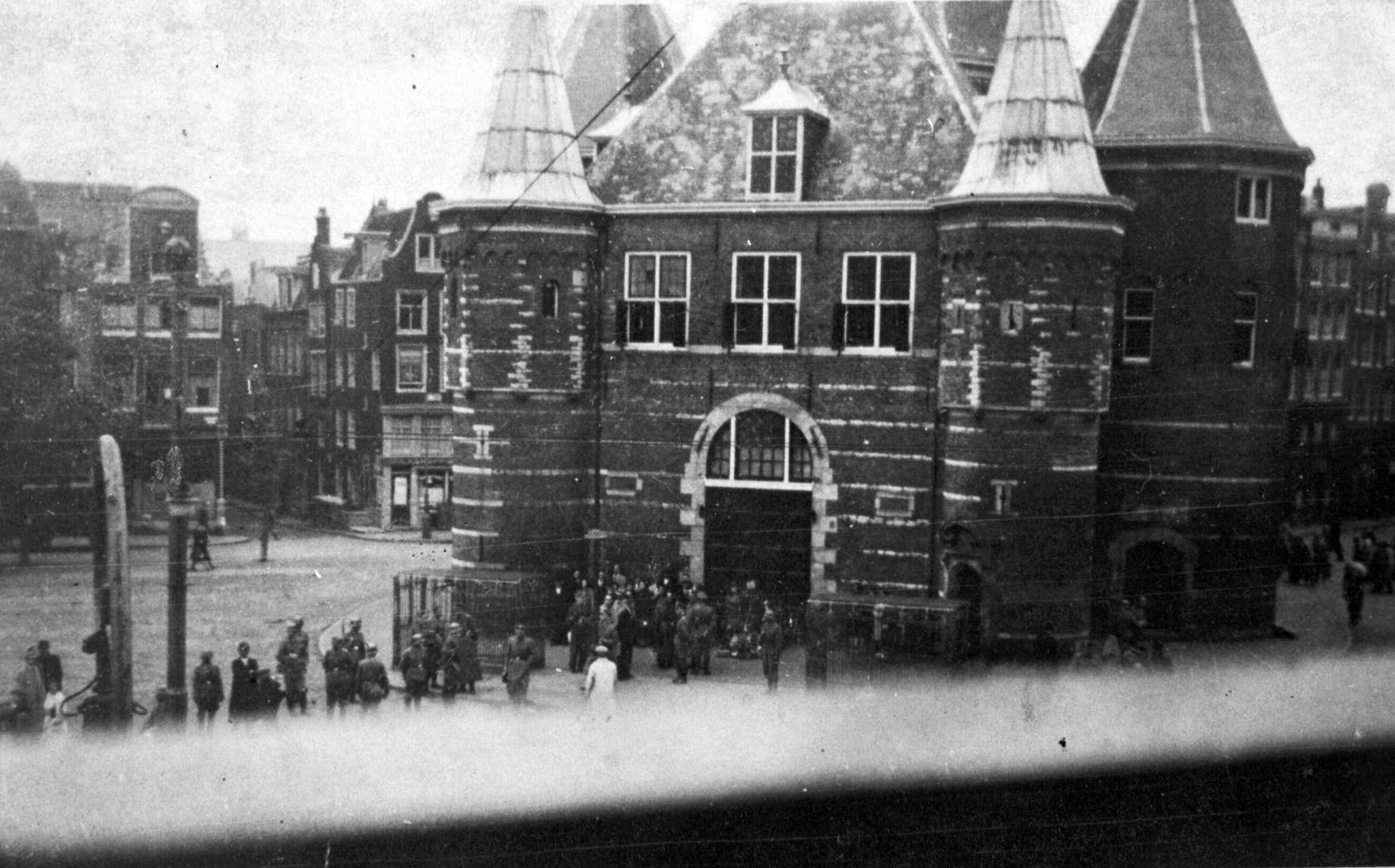

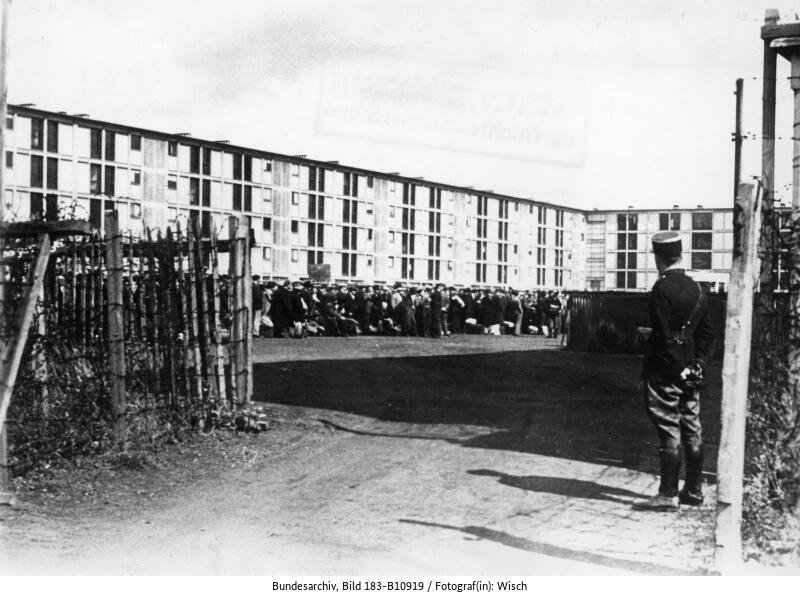

Mass raids in Amsterdam: The first deportations of Dutch Jews

22 and 23 February, 1941 Amsterdam

On Saturday 22 and Sunday 23 February 1941, the Ordnungspolizei (German police) rounded up Jewish men at Jonas Daniël Meijerplein in Amsterdam. Almost 400 men between the ages of 18 and 35 were arrested, forcibly pushed into lorries and deported. The razzia was Nazi punishment for fights that had occurred between Jews, antisemitic thugs, and the German police.

In the weeks prior to the raid, the atmosphere in Amsterdam had been turbulent. Assault groups of the NSB (the Dutch National-Socialist Movement) had constantly been looking to confront Jews. This had caused a lot of fighting. On 11 February, an NSB member was so badly injured that he died a few days later. The antisemitic press blamed it all on the Jews.

Shortly thereafter, unknown thugs smashed the windows of Koco ice cream parlour, a company run by two Jews who had fled Germany. In response, Jewish and non-Jewish customers formed their own assault team to protect the store. When the Ordnungspolizei raided the shop on 19 February, their faces were sprayed with ammonia.

The German authorities did not put up with the attack on their police officers. To put an end to the unrest, they decided to hold a razzia in the weekend of 22 and 23 February.

The Jews who were arrested were taken to Camp Schoorl, where eight of them were released. From there, they were deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp and then to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Only two of them survived.

The owners of Koco ice cream parlour were severely punished. Ernst Cahn was executed by the Germans on the Waalsdorpervlakte, in the dunes near The Hague, on 3 March 1941. Alfred Kohn died in Auschwitz.

The Amsterdam population was shocked by this brutal German action. A few days later, a major strike was organised in protest.

Operation Barbarossa: Germany invades the Soviet Union

June 22, 1941 Soviet Union

On 22 June 1941, Germany began a major attack on the Soviet Union, the communist state that consisted of Russia and a number of neighbouring countries. The attack was code-named 'Operation Barbarossa', and Hitler and the army had been preparing its execution for months. Three million German soldiers crossed the border. This effectively ended the nonaggression pact that the two countries had concluded before the invasion of Poland in 1939. There were three fronts: one aimed for the Baltic States in the north, a second was headed towards Moscow and a third attacked Ukraine and southern Russia.

The German invasion surprised the Soviet leadership. Stalin, the country's dictator, had not believed that Germany was sufficiently prepared for war. But then, neither was he, and so the German troops were able to advance without much resistance. Hitler hoped that winning the war would not take long, because the strategic position and the grain and oil reserves of the Soviet Union were indispensable if Germany wanted to keep Europe in its grip. During the first nine months of the advance, one million German soldiers were killed.

Germany was waging a war of destruction against the Soviet Union. It was the largest communist country in the world and the Nazis considered the communists their greatest enemies, in addition to the Jews. Moreover, the Nazis regarded the Russian people and the peoples in the Asian part of the Soviet Union as inferior. They would have to make way for German settlers. For that reason, the German army treated the population and the captured soldiers inhumanely. Millions of people died of hunger or diseases, or were executed.

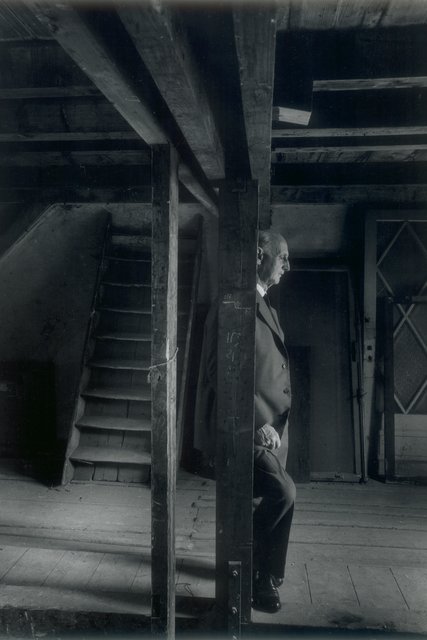

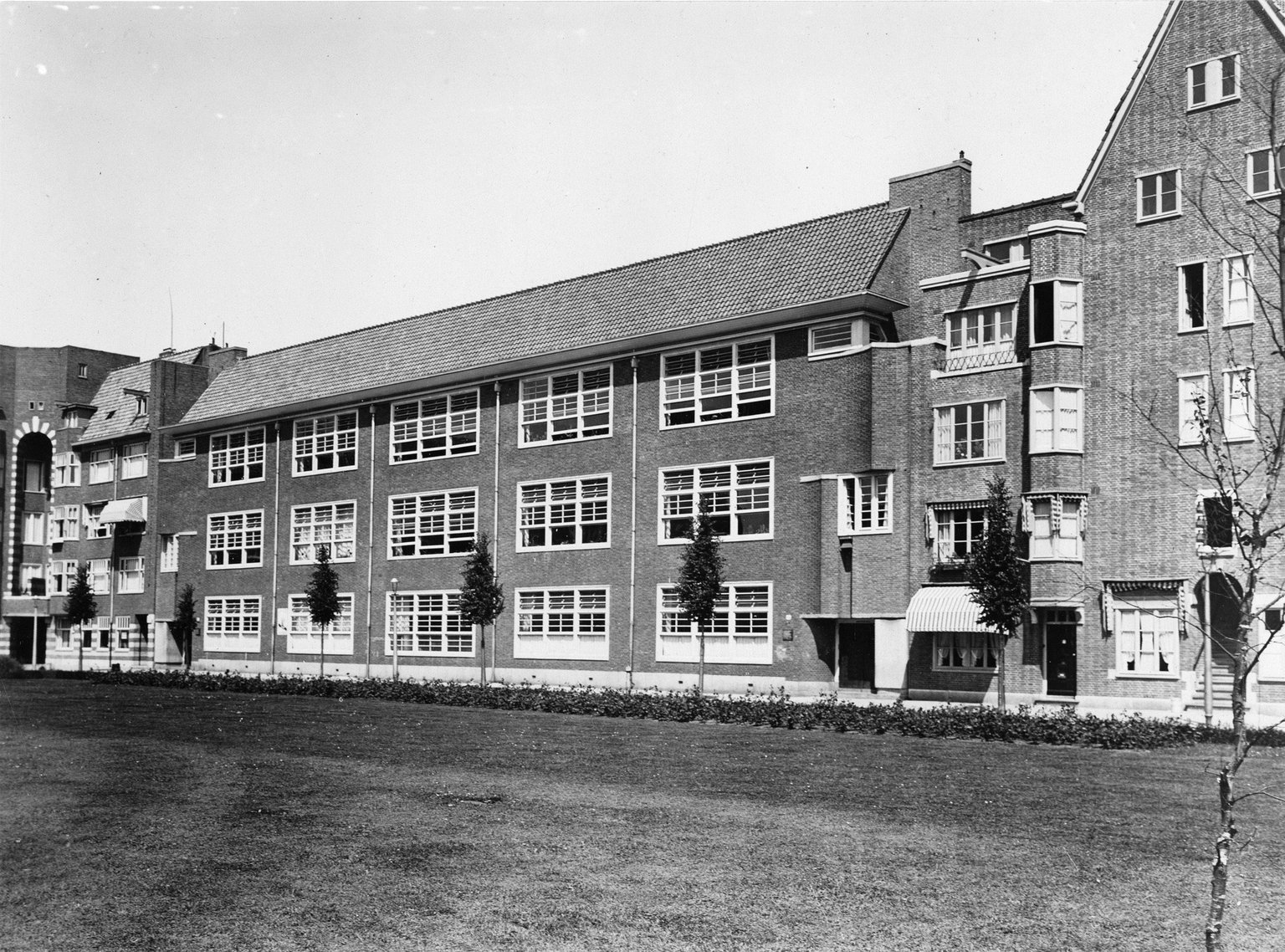

The old hiding place becomes a museum: the Anne Frank House

May 3, 1960 Amsterdam

The annex at Prinsengracht 263 opened its doors to the public on 3 May 1960. The restoration was not finished yet, but the Secret Annex could be visited. The main building was furnished to accommodate exhibitions and a documentation centre.

At Otto's request, the Secret Annex was kept unfurnished. After the arrest of the people in hiding, it had been emptied by the Nazis and he wanted to keep it that way.

On the occasion of the opening, Otto Frank said: ‘I apologise for not speaking from this house after today. You will understand that the memories of everything that happened here are too powerful. I can only thank you all for the interest you have shown in coming here. And I hope that you will continue to support the work of the Anne Frank House and the International Youth Centre, morally and in every other respect.’

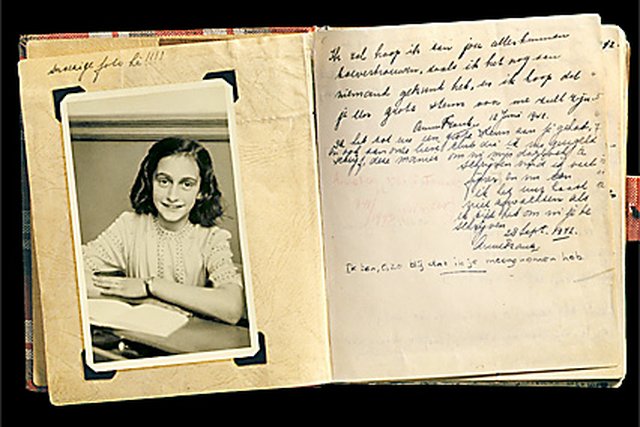

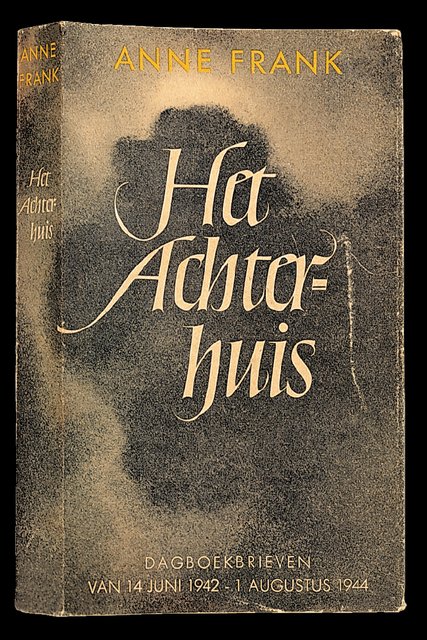

Anne's wish comes true: ‘Het Achterhuis’ (‘The Secret Annexe’) is published

June 25, 1947 Amsterdam

Anne's wish came true on 25 June 1947 when her book was published: Het Achterhuis. Dagboekbrieven van 14 juni 1942 - 1 augustus 1944 (The Secret Annex. Diary letters from 14 June 1942 - 1 August 1944). 3,000 copies were printed for the first edition.

Anne Frank: ‘Just imagine how interesting it would be if I were to publish a romance of the "Secret Annexe," the title alone would be enough to make people think it was a detective story.’

The book was well-received in the Netherlands, and the first Dutch edition soon sold out. In December 1947, after only six months, the second edition was published.

The people in hiding are discovered: They are arrested and put in prison

Aug. 4, 1944 Amsterdam

In the morning of 4 August 1944, Otto Frank was helping Peter van Pels with his language lessons. Edith was in her room. Police officers turned up at Prinsengracht 263 in Amsterdam. They went up to the office on the first floor where the helpers of the people in hiding were working. The police officers questioned Victor Kugler and searched the building in his presence. They ended up on the landing with the revolving bookcase and discovered the hiding place and the people who lived there.

Together with two of the helpers, Johannes Kleiman and Victor Kugler, the people from the Secret Annex were taken to the SD prison on Euterpestraat. They were interrogated one by one to find out whether they knew of any other addresses where people might be in hiding. Johannes and Victor kept silent. Otto Frank said that after 25 months in the Secret Annex, they had lost all contact with friends and acquaintances and therefore knew nothing.

After the interrogations, the people from the Secret Annex and the helpers were separated. Johannes Kleiman and Victor Kugler were taken to the detention centre at Amstelveenseweg, the eight people from the Secret Annex to the detention centre at Weteringschans. Helpers Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl were not arrested. After a little while, they went up to the empty hiding place. There, they discovered Anne's diary papers, which were left behind after the arrest. Miep held on to the diary until after the war.

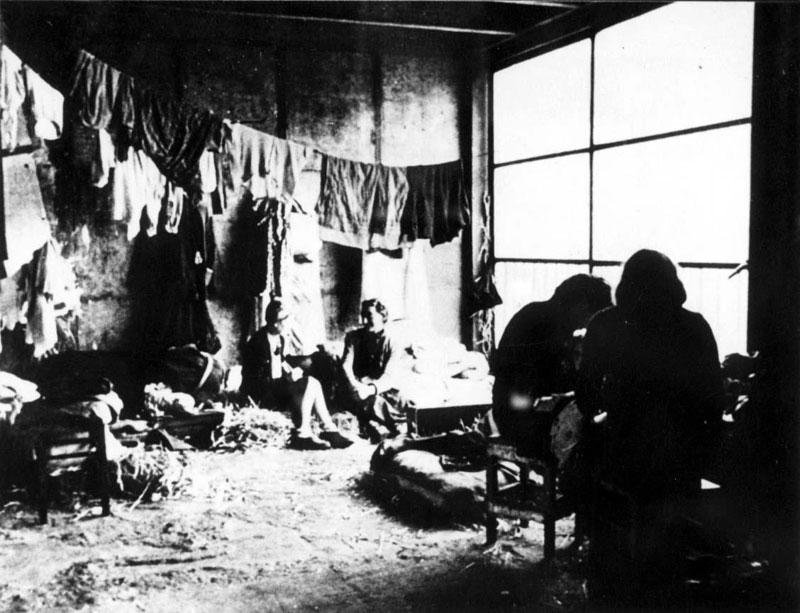

Anne and Margot die exhausted in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

February 1945 Bergen-Belsen

In late 1944, Anne and her sister Margot were taken from Auschwitz to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in a crowded train. Their mother Edith was left behind in Auschwitz.

In Bergen-Belsen, Anne Frank ran into children she had known in Amsterdam. She talked to Nanette Blitz and Hanneli Goslar, for example, two girls she had gone to school with.

In the winter of 1944-1945, the situation in Bergen-Belsen deteriorated. There was little food, and the camp was filthy and crawling with vermin. Many prisoners fell ill. Margot and Anne Frank contracted spotted typhus and died in February 1945. Nothing is known about their final days.

(Quote by) Rachel van Amerongen: ‘One day, they just weren't there anymore.’

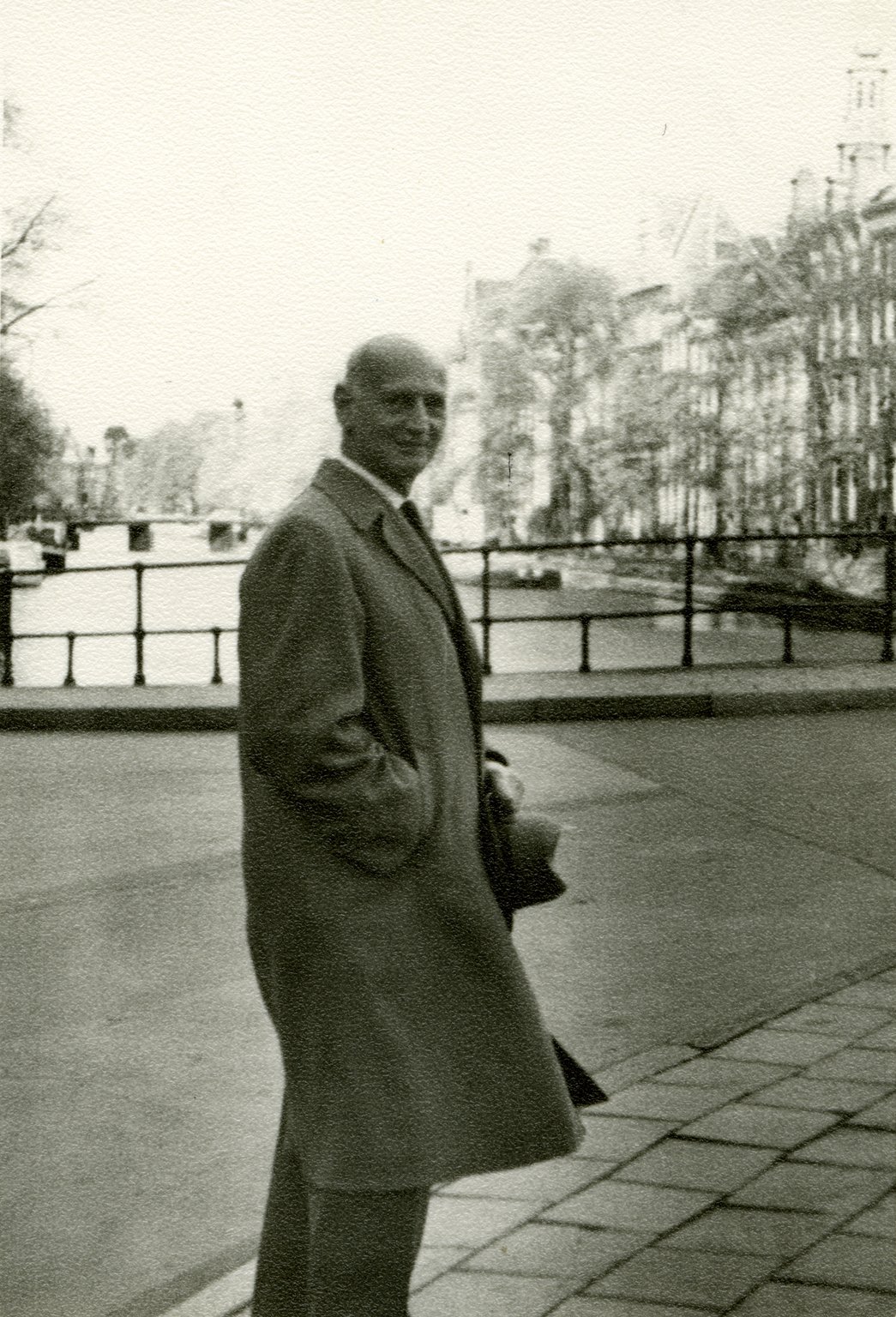

Otto returns to Amsterdam

June 3, 1945 Amsterdam

On 21 May 1945, Otto left the Ukrainian port of Odessa aboard the ‘Monowai’. Six days later, he arrived in the port of Marseille. Almost immediately, he travelled on to Amsterdam, where he showed up on the doorstep of helpers Jan and Miep Gies in the evening of 3 June. Johannes Kleiman and his wife and Fritz Pfeffer's fiancée immediately came over to greet him. The other helpers had survived the war as well.

Although Otto knew that Edith had died, he did not know what had happened to Anne and Margot. Every day, he went to Amsterdam Central Station, hoping to find them among the travellers returning from the concentration camps, and he placed an ad in the newspaper, hoping for news. He also got involved in the Opekta and Pectacon companies again.

Anne receives a diary

June 12, 1942 Amsterdam

For her thirteenth birthday, Anne Frank received a diary. ‘Maybe one of my nicest presents…’ she wrote about the red-checked book. The diary did not come as a surprise, because Anne had picked it out herself...

On the cover page, she wrote: ‘I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support. Anne Frank. 12 June 1942.’

Two days later, she wrote the next entry. She wrote about what happened and who were there, her birthday party, her gifts, her friends, being in love, her family history, and her school class.

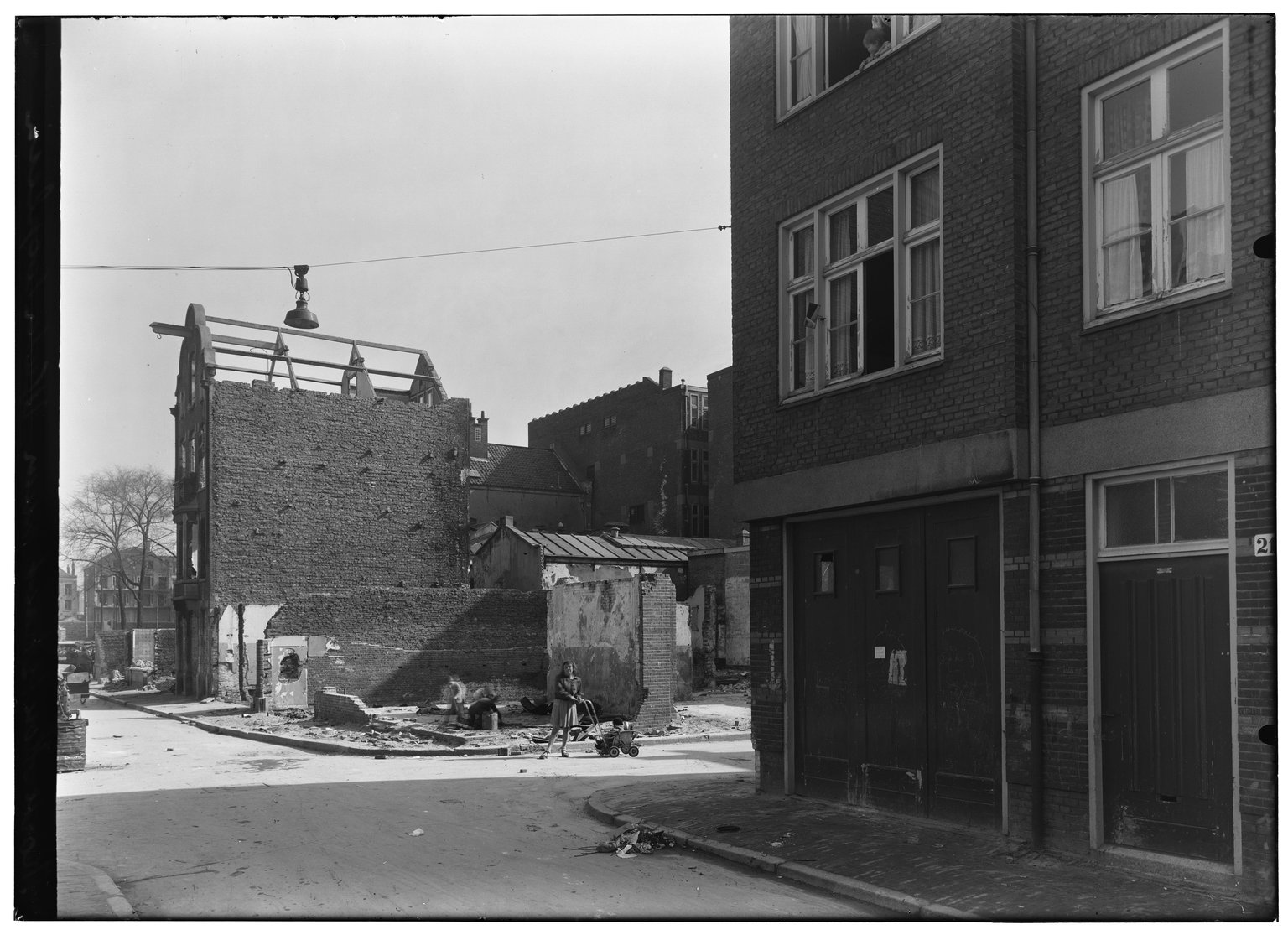

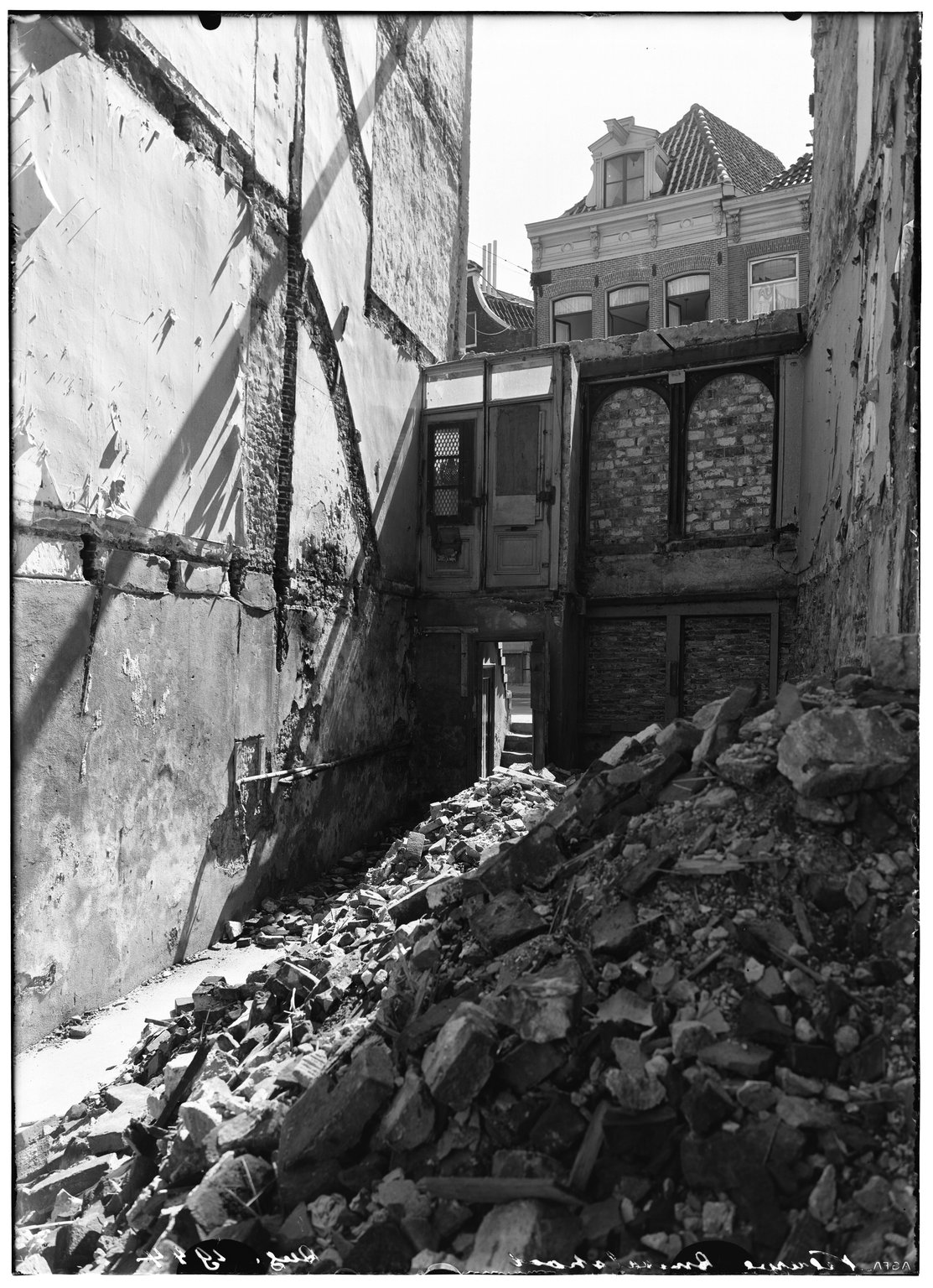

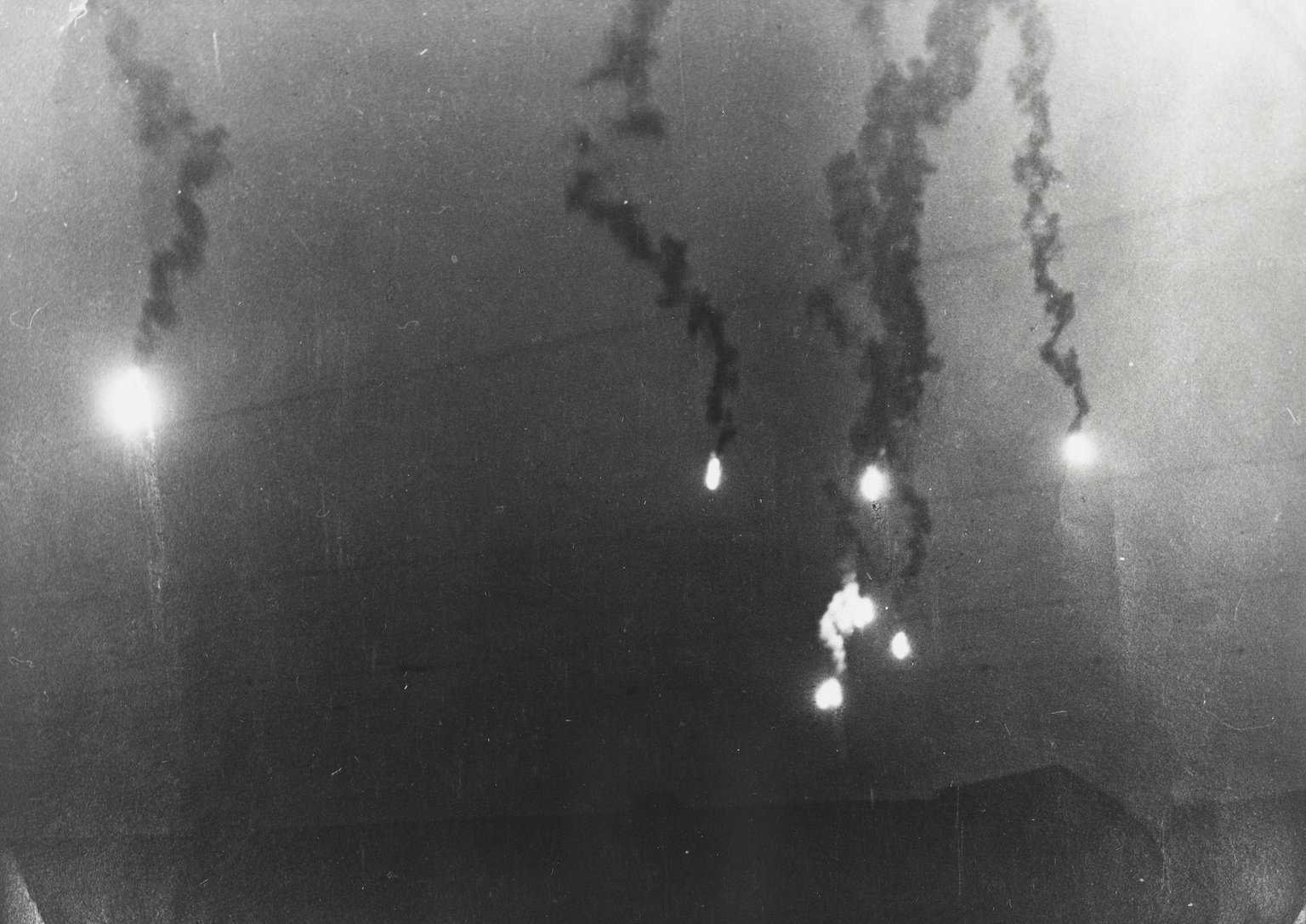

Germany bombs Rotterdam. The Netherlands surrenders

May 14, 1940 Rotterdam

Rotterdam was an important target of the German attack on 10 May 1940. Paratroopers and soldiers who had landed on water tried to conquer the bridges. The Dutch army offered fierce resistance and the Germans failed to take the city. On 14 May, German general Schmidt gave the Dutch commander an ultimatum: if Rotterdam did not surrender that same afternoon, the city would be bombed.

The negotiators in Rotterdam did not know that the military leadership in Berlin had other plans. Hermann Göring, leader of the Luftwaffe, planned to bomb civilian targets to force the country to surrender. Even before the ultimatum had expired, German planes started dropping their bombs on downtown Rotterdam. When the smoke cleared, close to 80,000 people were homeless and around 850 people had died.

Germany threatened to bomb Utrecht as well. The Netherlands had no other option than to surrender. In a school building south of Rotterdam, General Winkelman signed the capitulation agreement on 15 May. With his signature, the Netherlands officially surrendered.

The defeat was hard on the Dutch military and civilians. Even so, many Dutch people were also relieved that the tension had subsided. Things were different for many of the Dutch Jews. They had heard terrible things about the Nazis. Now the Nazis had come to the Netherlands as well, and they were terrified. In the months following the invasion, hundreds of Jews committed suicide.

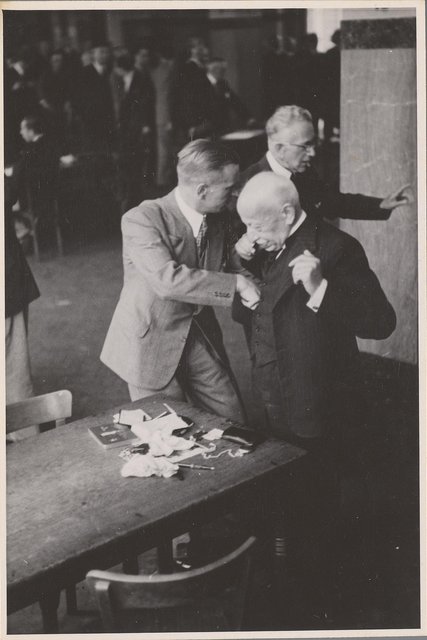

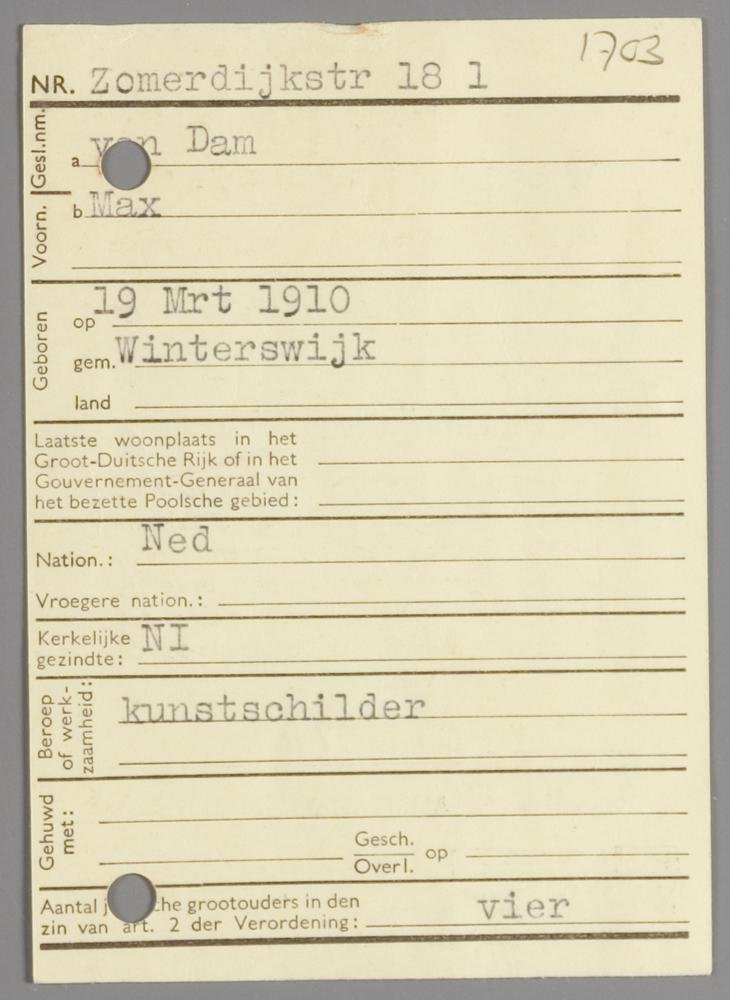

The Dutch government makes carrying an identity card compulsory

April 1, 1941 The Netherlands

From April 1941 onwards, every Dutch person aged 15 years or over had to have an identity card. This identity card had a passport photograph and a fingerprint of the bearer as well as a unique number. Large capital ‘J’s were later stamped onto the documents of Jews, to make them instantly recognisable. From 1 January 1942, everyone had to carry their card with them at all times.

For the Nazis and the Dutch police, identity cards were an important tool in tracking down Jews, resistance fighters, and people who wanted to avoid compulsory employment. The identity card had been developed by Dutch civil servant Jacob Lentz. He was also the one who set up the population register and the registration of Jews.

Because of the special ink, stamps, glue, and watermarked paper that were used, forging identity cards was almost impossible. Moreover, the identity card’s unique number could be used to check the data against the local or national public registers.

In this way, even ordinary police officers were able to detect almost perfect forgeries if they checked them thoroughly. The only way to forge identity cards was by feeding the data of non-existent people into the central administration. These data could then be used to create new identity cards. This required the cooperation of reliable civil servants.

Lentz's perfectionism cost many of his compatriots their lives and caused great problems for many others.

The last months in Frankfurt

March 10, 1933 Frankfurt

Anne, Edith, and Margot Frank in a passport photo booth with a scale in Tietz department store in Frankfurt. This is one of the few surviving photos from that time.

In March 1933, they moved to the home of their grandmother Alice Frank in Frankfurt, with whom Otto and Edith had also lived after their wedding.

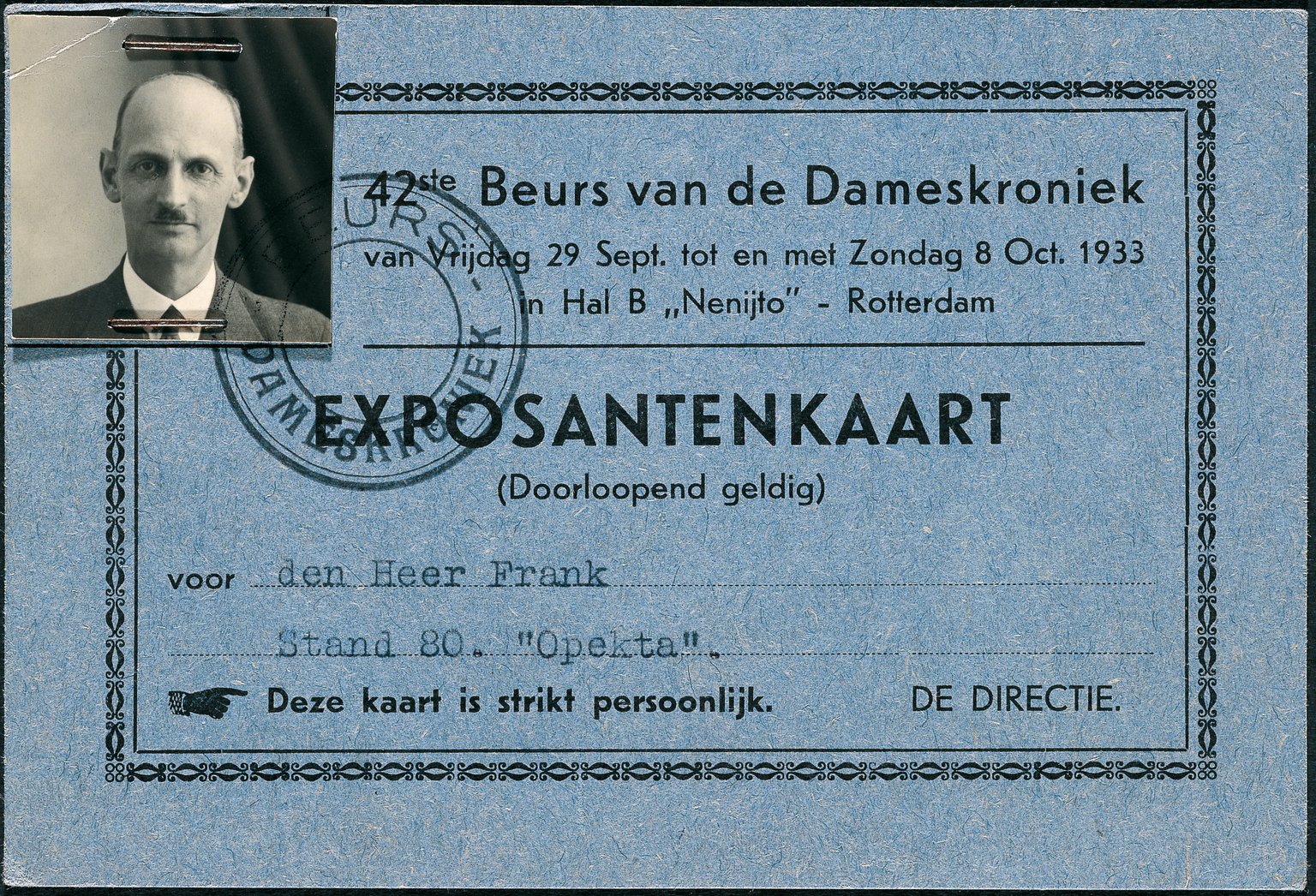

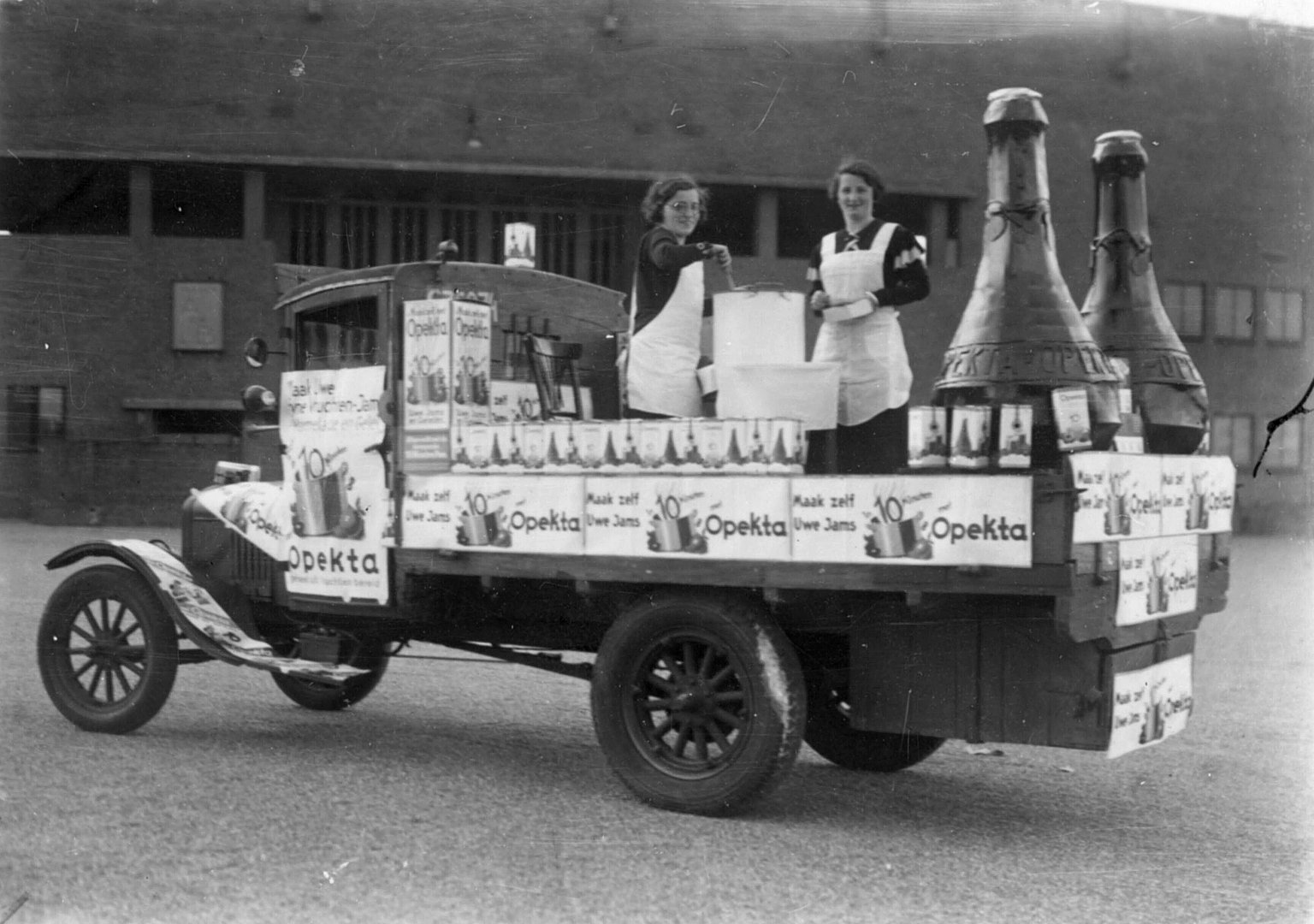

Otto starts Opekta in the Netherlands

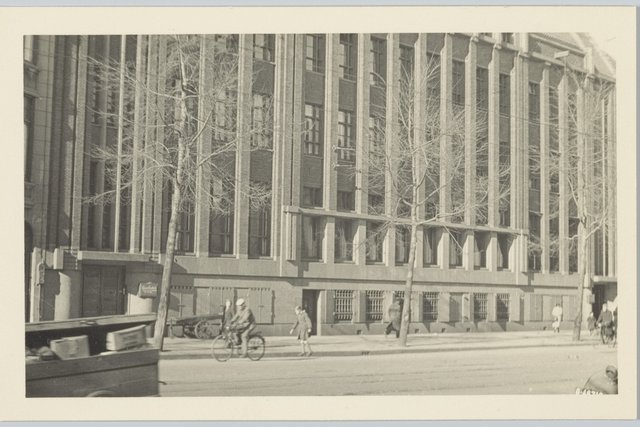

July 4, 1933 The Netherlands

In August 1933, Otto moved to Amsterdam. He had frequently been in the Netherlands before on account of his company Opekta. His firm was the Dutch branch of a German company. Opekta, the product, was used in jam-making. It was sold in shops. Opekta advertised widely in Germany and Otto adopted their advertising for the Netherlands. The first Opekta advertisements were printed in Limburg newspapers.

The company started in July 1933. In late September, Otto had a stand at a trade fair in Rotterdam, where modern companies introduced their products to the general public. Many more demonstrations for Dutch housewives were to follow.

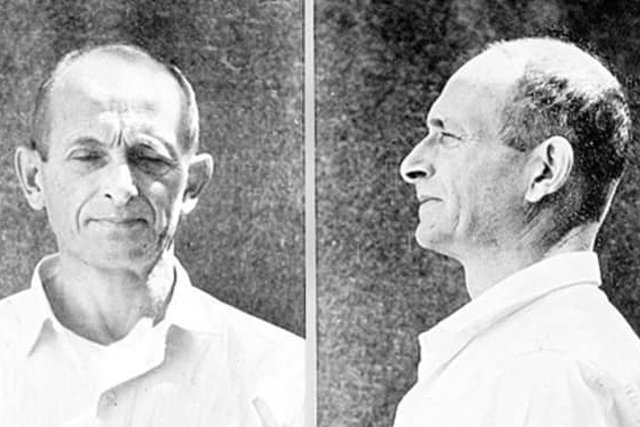

Eichmann invades the Jewish Congregation in Vienna

March 18, 1938 Vienna

On 18 March 1938, SS-Oberstürmbannführer Adolf Eichmann and a group of Nazis raided the Jewish Congregation in Vienna. They searched the building and arrested the members of the Board. They were imprisoned at Dachau concentration camp. The Jewish Congregation was dissolved by the Nazis.

Some time later, Eichmann brought director Josef Löwenherz back from captivity and reopened the Congregation. Eichmann wanted to use him and his organisation to force the Jews out of Austria. Löwenherz had long been involved in the emigration of Jews to Palestine and had many international contacts. Other Jewish organisations were forced to cooperate as well.

This was the beginning of the ‘Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung’ (Centre for Jewish Emigration). Despite its neutral name, it was an organisation of the SS (Schutzstaffel, the military branch of the Nazi party). Its goal was to get the Jews to leave the country as soon as possible and to take their money before they went. The money of wealthy Jews was used to pay for the emigration of poor Jews. It worked so well, that the SS opened other centres like it in Berlin and Prague.

Eichmann's idea of involving Jewish organisations in Nazi politics was also adopted elsewhere in the form of Jewish councils. He cleverly abused the Jews’ hope that they would be able to save themselves.

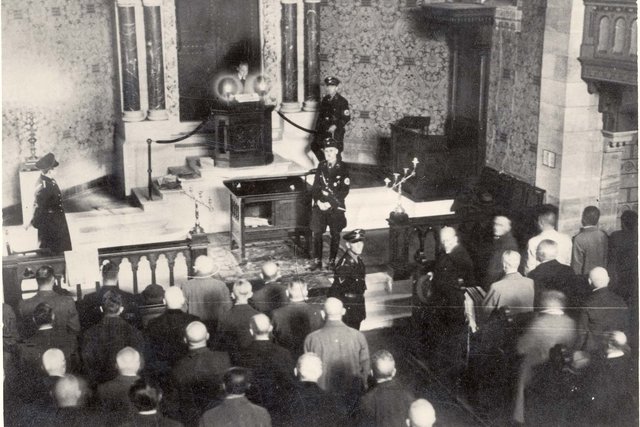

Consecration of the Liberal Jewish Synagogue in Amsterdam

June 6, 1937 Amsterdam

The Liberal Jewish Congregation in Amsterdam was founded in 1931. Its membership increased as a result of the large numbers of Jewish refugees from Germany. So, it needed space for its services. From 1937 onward, the temple of the Theosophical Society was rented and used as a synagogue. The consecration was attended by Heinrich Stern, the chairman of the Liberal Jews in Germany.

Otto, too, was liberal Jewish and involved in the establishment of the synagogue.

Otto Frank at a youth conference at the Anne Frank House

July 1968 Amsterdam

From 1963 onwards, every year young people from all over the world came to the Anne Frank House for international summer conferences on emancipation, religion, and human rights.

The International Youth Centre was enthusiastically run by educator and psychologist Henri van Praag, an acquaintance of Otto Frank’s. In the 1960s, the Anne Frank House organised lectures and courses.

Rabbi Yehuda Aschkenasy, an Auschwitz survivor, ran meetings to promote understanding between Jews and Christians. These meetings drew priests, vicars, rabbis, as well as regular believers.

During this period, the Anne Frank House was also used for literature, poetry, or classical music events. The performers at the concerts were mostly young students from the school of music.

In the second half of the 1960s, the Anne Frank House made room for social criticism. Photo exhibitions and other means were used to protest the war in Vietnam and apartheid in South Africa.

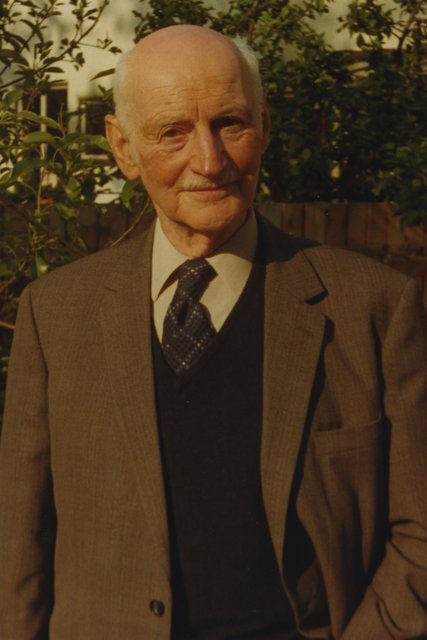

Johannes Kleiman with visitors in the Secret Annex

1955 Amsterdam

After Otto Frank had moved to Switzerland in 1952, Johannes Kleiman once again became managing director of Opekta. In 1955, Opekta and Gies & Co moved to other buildings in the city. By then, people from different parts of the world were already interested in visiting the Secret Annex where Anne Frank had lived in hiding.

Whenever people asked him to, Kleiman returned to the empty building on Prinsengracht to give visitors a tour of the hiding place.

Otto dies

Aug. 19, 1980 Basel

On 19 August 1980, Otto Frank died in Basel at the age of 91. The news of his death was noted around the world. Fritzi Frank-Markowitz, his widow, received hundreds of letters of condolence. Dutch rabbi Avraham Soetendorp conducted the funeral service.

Anne's diaries and other writings were transferred to the Dutch state and are now managed by the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD). The copyright on Anne Frank's writings is now held by the Anne Frank Fonds in Basel, Switzerland.

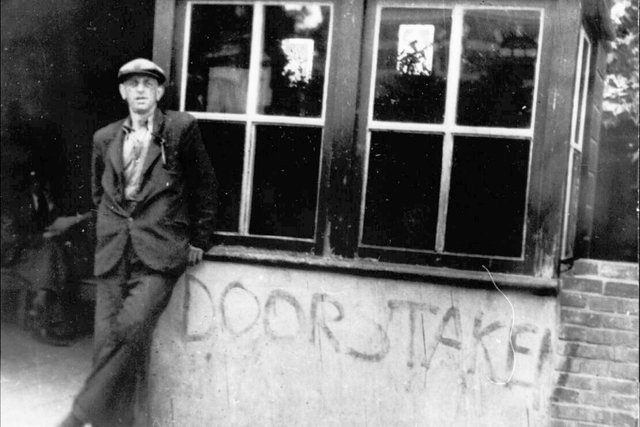

Mad Tuesday: German soldiers and collaborators on the run

Sept. 5, 1944 The Netherlands

In the garden of a house in Amsterdam, between Keizersgracht and Kerkstraat, German soldiers had left their weapons. Like many other German soldiers, they were in a hurry to leave on Tuesday, 5 September 1944. They had heard that the Allies had crossed the Dutch border in the south and were advancing rapidly to the north of the Netherlands. Within a few days, the troops that had stayed back had destroyed the ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam with explosives.

For fear of retaliation, many collaborators were afraid to stay in the Netherlands as well. They left on the same day, heading for the east of the Netherlands or Germany.

The German occupying forces decided to evacuate the Vught concentration camp and deported 2,800 men to Sachsenhausen and 650 women to Ravensbrück, two concentration camps in Germany. About half of them eventually died there.

Many Dutch people raised the Dutch flag and took to the streets. However, the news of the arrival of the Allied Forces was premature. They had only been in Belgium for a few days and it would take another week before the first towns in the Netherlands were liberated.

This day would soon be known as ‘Dolle Dinsdag’ or ‘Mad Tuesday’.

The Van Pels family goes into hiding

July 13, 1942 Amsterdam

A week after the Frank family went into hiding, Hermann and Auguste van Pels, and their son Peter, joined them in the hiding place. The Van Pels family were given two rooms on the second floor of the Secret Annex to use. They had little privacy. The room of Hermann and Auguste was also used as a kitchen and dining room. Peter’s room had stairs to the attic, where the people in hiding stored their food.

Hermann and Otto had prepared the hiding place together with their colleagues Victor Kugler and Johannes Kleiman. Hermann and Auguste's room had been a laboratory for trying out recipes. The equipment and other things had been moved to the office kitchen below Anne's and Margot's room.

Peter had brought his bike and hung it from the ceiling of his room.

The February Strike

25 and 26 February, 1941 Amsterdam

On 25 February 1941, the local section of the CPN (Communist Party of the Netherlands) called a two-day strike in protest against the raid on Jewish men a few days earlier.

The action started with the shutdown of the tram transport in Amsterdam, which was how many people noticed that something was going on. The strike then spread to other towns and villages in the area.

The Germans were surprised by the protests and responded with brute force. They shot at strikers, and several people were wounded or killed. Many strikers were arrested. The cities where the strike took place were heavily fined.

The mayors of Amsterdam and Zaandam were replaced. A German-minded police commissioner was appointed in Amsterdam.

Otto’s first time in Amsterdam

Jan. 1, 1923 Amsterdam

From 1923 to 1929, Otto and his brother Herbert and brother-in-law Erich Elias ran a bank branch in Amsterdam called M. Frank and Sons. It was located in the city centre. Due to the economic problems in Germany, many German banks opened branches in Amsterdam. As soon as the economic situation improved, many of them were closed again, including the Franks’ branch.

Johannes Kleiman was in charge of current affairs and discussed them with the management. Later, Kleiman was involved in Opekta and the founding of Pectacon.

Germany agrees on an armistice with the United Kingdom and France

Nov. 11, 1918 Compiègne

By the autumn of 1918, it became clear that Germany was not going to win the war. Its opponents had too much economic and military strength. Besides, more and more allies of Germany were giving up the fight. Germany itself was in great turmoil as well. There was no other option than to end the war.

On 9 November 1918, the Allies and the Germans convened in a railway carriage in the forest of Compiègne, a small town 60 kilometres to the north of Paris. The German delegate Matthias Erzberger tried to negotiate about the terms of the armistice. The Allies did not yield. They wanted Germany to surrender. Two days later, on 11 November, Germany signed the truce, which started at 11.00 am on the same day.

Germany lost a lot because of the armistice. The agreement demanded that all German troops would withdraw from French and Belgian territory within two weeks. The Rhineland, an area bordering on Belgium and France, was to be occupied by Allied troops. Germany had to return territory in Eastern Europe it had conquered during the war. Moreover, Germany had to donate large quantities of military equipment to the Allies.

Otto Frank and Edith Holländer get married

May 12, 1925 Aachen

On 8 May 1925, Otto Frank and Edith Holländer got married at city hall in Aachen. They had met a few years earlier, when Otto's brother Herbert got engaged to a friend of Edith’s in Aachen.

On 12 May, Otto's 36th birthday, their marriage was solemnised in the synagogue of Aachen. In the evening there was a large banquet for all their guests. After the wedding, Otto and Edith went on honeymoon to San Remo in Italy.

The first year and a half of their marriage, they lived with Otto's mother Alice Frank-Stern in Frankfurt am Main.

The German army uses poison gas against French troops

April 22, 1915 Ypres

During the First World War, the warring parties tried everything they could think of to win. The German army was the first to use deadly poison gas on the Belgian battlefields.

On 22 April 1915, French troops saw a yellow-green cloud of chlorine gas coming towards them. Within ten minutes, thousands of soldiers had choked to death. The German attack violated international agreements that prohibited the use of poison gas. Afterwards, the French and English also resorted to the use of poison gas.

The United States declare war on Germany

April 6, 1917 Washington

On 6 April 1917, American president Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany. Until that day, the United States had remained neutral. The declaration of war was a response to the submarine war that Germany had been waging on its enemies since January 1917.

Germany wanted to sink all ships sailing toward the United Kingdom, including passenger ships and neutral American ships, as they could be carrying aid - from food to soldiers - for Germany's opponents. Germany knew that the United States would respond, but they believed that the United States would take so long to prepare, that the British would have quit their efforts by then. But they were wrong.

Another reason for the American declaration of war was the interception of the so-called "Zimmermann telegram”, in which Germany promised Mexico financial support and American territory if it would attack the United States. Mexico refused the request. The telegram had been sent in code, but it was deciphered by the English secret service. The Americans were outraged.

In 1917, the United States sent more than a million troops to France. It took another year before they were fighting alongside the Allies in substantial numbers.

Famine in Germany

1917-1919 Berlin

By the end of the First World War, famine raged in Germany. People desperately tried to find food. In Berlin, for instance, hungry women and children cut up a horse in the street. The animal had been killed in a fight between government troops and insurgents. In spite of the shooting that was still going on around them, the starving women and children threw themselves on the horse.

At the start of the war, Germany's enemies had put up a naval blockade to stop all transports. This had led to a major food shortage in Germany. It was not until March 1919 that food was supplied to Germany again.

Failed coup in Germany

March 13, 1920 Germany

The Kapp Putsch was a coup committed by right-wing soldiers in Berlin. They overthrew the democratically elected government and replaced it with an authoritarian leadership, a leadership that controlled everything without having been elected. The government fled to the German city of Stuttgart. For six days, the coup fighters had control over Berlin, but they did not know what to do with their power and they were not supported by the people. Before long, a major strike broke out, which brought the whole city to a standstill. The putschists gave up. The government returned but did little to punish them.

Before long, other attempts were made to remove the democratically elected government. A year later, in March 1921, communists committed attacks and called strikes in an attempt to start a workers' uprising. The government suppressed the uprising after two weeks.

Rent strike in Berlin

Sept. 1, 1932 Berlin

The government's cutbacks were causing great poverty among the German population. In Berlin, workers jointly stopped paying rent in protest against the high rents and the poor condition of their houses.

Köpenicker street was the centre of the rent strike.

The slogan ‘First food - then rent’ is painted on the wall in the background. Flags of the Communist Party and the Nazi Party hang from the windows. Both sides appealed to the workers because they promised to solve the problems of poverty, each in their own way.

The Iron Front marches against the Nazis

March 1, 1932 Berlin

On 16 December 1931, the Iron Front was founded. It was an armed partnership of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), trade unions, and other social democratic organisations. The SPD was a supporter of the republic and was fought by the communists and the Nazis. Because of the increasing violence of these parties, the SPD and its allies felt it necessary to take up arms themselves. Their logo shows three arrows pointing to the lower left inside a circle.

The Enabling Act: even more power for Hitler

March 23, 1933 Berlin

On 23 March 1933, the German parliament voted in favour of the ‘Enabling Act’ by a large majority. The Act allowed Hitler to enact new laws without interference from the president or the Reichstag (German parliament) for a period of four years.

In his speech on that day, Hitler gave those present the choice 'between war or peace'. It was a veiled threat to intimidate any dissenters. With 444 votes in favour and 94 against, the Reichstag adopted the Enabling Act. Only the Social Democrats voted against it. The vote could hardly be called democratic: The Reichstag was surrounded by members of the SA and the SS, the armed branches of the NSDAP. The Communist Party was absent because its members had been arrested or were on the run. Twenty-six Social Democrats did not vote for the same reason.

This law allowed Hitler to rule Germany as a dictator from then on.

Germany is a one-party state

Dec. 1, 1933 Germany

On 1 December 1933, the German government adopted a law stating that the NSDAP and the German State were inextricably linked. This meant that the government was bound to support the Nazi party and that the party also had power outside of the government. For example, the NSDAP now was entitled to arrest people itself.

The law was the official confirmation of a situation that had existed for some time. In the preceding months, the Nazis had dealt with the other political parties in Germany. The Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party had been banned. Other parties had dissolved themselves.

A law of 14 July 1933 made the NSDAP the only political party in Germany and prohibited the creation of new political parties. On 12 November 1933, new parliamentary elections were held. There was only one party on the ballot: the NSDAP, with Hitler as its leader.

Factory workers practise wearing gas masks

Sept. 13, 1933 Brandenburg, Germany

The government felt that the Germans should prepare for war, even though there was no indication that Germany was under threat. Still, the population had to learn what to do in case of an enemy attack with poison gas.

The German Luftwaffe bombs Guernica

April 26, 1937 Guernica

On 26 April 1937, German bombers of the Condor Legion, together with the Italian Air Force, bombed the Spanish town of Guernica. Hundreds of civilians were killed, and large parts of the town were destroyed. Worldwide, the bombardment had a great impact.

A civil war had been raging in Spain since 17 July 1936. On that day, a group of nationalist army officers, the later dictator Francisco Franco among them, staged a coup against the republican government. They were supported by rightwing and conservative groups. Leftwing parties such as the communists and anarchists stood by the government.

Both sides received support from abroad. The republicans received moral support from Europe and America and weapons and troops from the Soviet Union. The nationalists were supported by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. After three years, on 1 April 1939, the fighting ended in a victory for Franco.

The bombardment of Guernica was the first action of the modern German army. In May 1939, the Condor Legion was given a warm welcome when they returned to Hamburg and Berlin after Franco's victory.

The Anschluss: Germany occupies Austria

March 15, 1938 Vienna

On the morning of 12 March 1938, the German army invaded Austria. No one stopped it. Hitler arrived later that day. He visited his place of birth and his parents’ grave. Three days later, on 15 March, he gave a speech in Vienna and officially declared that Austria was now part of the German Empire: the Anschluss. Austria had become a German province: the Ostmark. Hitler appointed Arthur Seyss-Inquart governor.

Many Germans and Austrians were as enthusiastic as Hitler. They had wanted the countries to be joined for a long time.

On 10 April, the Nazis organised a referendum, meant to legitimise their military action. More than 99% of the Austrian population voted in favour of the Anschluss. Without a doubt, the percentage was so high because the vote was not anonymous. Opponents did not dare to vote against.

The takeover allowed the Austrian Nazis to flaunt their antisemitism. They visited Jews at home, robbed them and smashed their furniture. In Vienna, Nazis forced Jews to scrub pro-Austrian slogans off the streets. Many Jews tried to flee, others committed suicide. In two weeks’ time, more than 200 Viennese Jews took their own lives.

The Munich Agreement

Sept. 30, 1938 Munich

On 30 September 1938, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from a conference in Munich. Together with France and Italy, he had signed a treaty with Hitler. It stated that Hitler could add Sudetenland, the predominantly German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia, to the German Empire. In exchange, Hitler abandoned his plans to usurp the rest of Czechoslovakia as well.

Later that day Chamberlain gave a speech in which he said: “A British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.” He believed that a war between Germany and Great Britain had been avoided. But many people did not believe so. The Munich Agreement symbolises a policy of appeasement. In their attempts to prevent war, the British and the French accepted Hitler's demands time and again.

Boycott of Jewish shops

April 1, 1933 Germany

On 1 April 1933, the Nazi regime organised a boycott of Jewish goods. SA men positioned themselves in front of shops of Jewish owners. They painted the Star of David on shop windows, got in the way of customers trying to enter the shops and carried signs with anti-Jewish slogans.

The boycott was a countermeasure to an appeal from Jewish organisations in the United States to boycott German products. They wanted to protest against the mistreatment and discrimination of Jews in Germany.

The boycott in Germany was not a great success. Many Germans did not care much, one way or the other, and the foreign press condemned the action. It was still an important moment in the development of anti-Jewish measures, though. For the first time, the Nazis showed clearly that they wanted to make life impossible for the Jews.

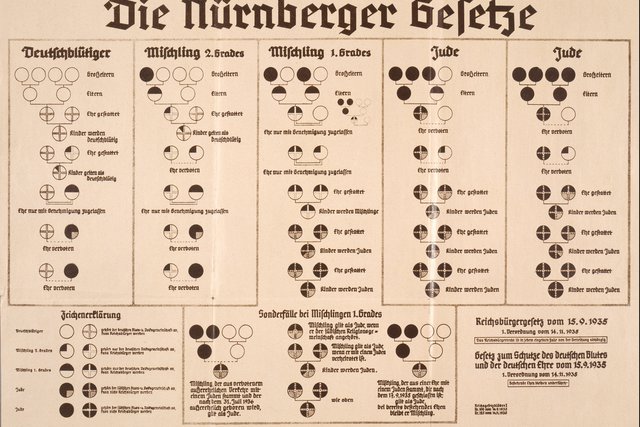

The Nuremberg Race Laws

Sept. 15, 1935 Nuremberg

On 15 September 1935, the Nazis introduced the Nuremberg Race Laws. These racist laws were directed against the Jews in Germany and essentially stripped them of their civil rights.

Based on family lineage, the laws determined who was Jewish and who was not. People with three or four Jewish grandparents were considered Jewish. Jews were no longer considered citizens and therefore could not claim certain civil rights, could no longer vote and could not work for the government.

Another section of the Nuremberg Laws was called the 'Law for the protection of German blood and German honour'. Under this law, marriages between Jews and Germans were forbidden. Moreover, Jews were not permitted to employ female citizens of German blood under the age of 45 as domestic workers.

The Nazis were horrified by relationships between Jews and non-Jews. In July 1935, for example, Julius Wolff and his non-Jewish fiancé Christine Neumann were paraded through the streets of Norden by the SA. They were forced to carry signs saying "Ich bin ein Rassenschänder" ("I defile the race") and “I am a German girl and I allowed a Jew to defile me”.

Christine was taken to a concentration camp and released after a month. Julius was locked up in the Esterwegen concentration camp. After his release, he fled to the United States.

The Gestapo deports Polish Jews to Poland

Oct. 27, 1938 Germany

In October 1938, the Polish government announced that they would refuse to admit Jews without valid passports if they had lived in Germany for more than five years. Many Jews wanted to return to Poland because of the anti-Jewish measures in Germany. To renew their passports, they had to get a stamp at the Polish consulate, but in many cases, they were denied the stamp. As a result, they were unable to leave Germany.

This was inconvenient for the Nazis: they wanted as many Jews as possible to leave the country, but many of the Jews in Germany were Polish. And so, Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Gestapo, decided to banish all Polish Jews.

The Polish Jews were forced by threats and violence to illegally cross the border with Poland. They had to leave their possessions behind. The people who were expelled were of all ages. Some were born in Germany and did not speak Polish.

However, the Polish authorities refused to accept them and so most of them had to stay in the no-man’s-land or in a camp in the Polish border area for a long time. Approximately 17,000 people were deported in this way.

Évian Conference: no room for Jewish refugees

July 6, 1938 Évian-les-Bains

On July 6, 1938, American president Roosevelt organised an international conference on Jewish refugees from Germany. Thirty-two countries convened in the French town of Évian-les-Bains. Among the participants were the United States, England, France, the Netherlands, Australia, Switzerland, Mexico, and a number of South American states.

Most government leaders said that they sympathised with the Jewish refugees, but they did not want to admit more refugees. They had already taken in so many refugees and were afraid of tensions between the newcomers and their own populations. Haiti and the Dominican Republic were the only countires willing to accept tens of thousands of refugees, but the United States would not allow Haiti's offer. In the end, several hundred Jews found refuge in the two countries.

And so, the conference yielded no measures to improve the situation of the Jewish refugees.

Jewish refugees in Amsterdam

December 1938 Amsterdam

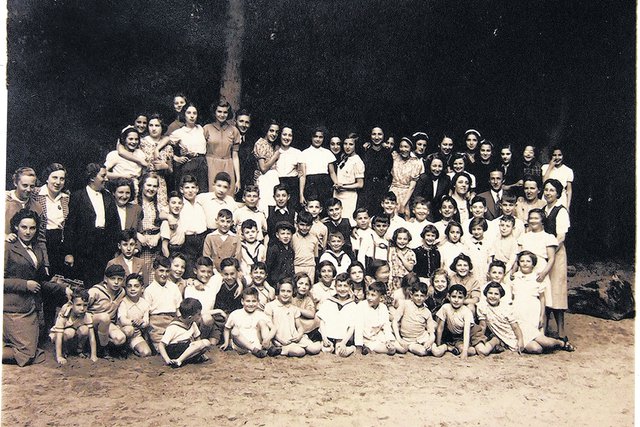

After the Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass) in November 1938, many German Jews fled to the Netherlands, but the Netherlands hardly allowed any of them in. The refugees who were allowed to stay received food from a Jewish aid organisation and help in finding shelter. Wounded refugees were cared for in a Jewish hospital.

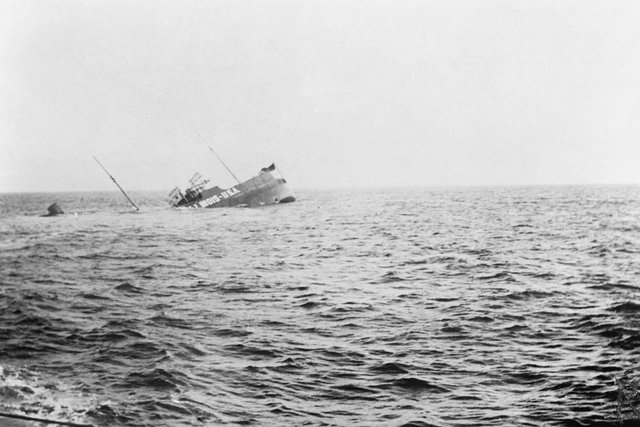

Refugee ship refused access

May 27, 1939 Havana

On 13 May 1939, the St. Louis left the port of Hamburg with 937 Jews on board, almost all of them Germans. They were headed for Cuba and believed that they had the right papers to be admitted. Two weeks later, on 27 May, the ship arrived in Havana, the capital of Cuba. However, only 28 passengers were allowed access, for the President of Cuba had declared the documents of the others invalid. Only one other man was later admitted to the country. He had to be taken to the hospital after a failed suicide attempt.

The ship sailed on to the United States, but that country did not allow anyone in. After a month, the ship sailed back to Europe. The journey ended in Antwerp. After negotiations, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Great Britain were prepared to accept a quarter of the passengers each. The refugees were finally allowed to go ashore.

Germany and the Soviet Union sign a non-aggression pact

Aug. 23, 1939 Moscow

In the night of 23-24 August 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact., known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

The countries agreed that they would not attack each other and secretly divided the countries that lay between them. Germany claimed Western Poland and part of Lithuania. The Soviet Union was going to occupy Eastern Poland, the Baltic States and part of Finland.

One week later, Germany invaded Poland and two weeks later, the Soviet Union attacked Poland in the east.

Germany invades Denmark and Norway

April 9, 1940 Denmark - Norway

Under the code name 'Operation Weserübung', Nazi Germany attacked Denmark and Norway on 9 April 1940. On that same day, Denmark surrendered and was occupied. The country was a useful base of operations for the fight against Norway. The Norwegians resisted for two months but surrendered on 9 June 1940. France and Britain helped Norway but were forced to withdraw when they were attacked themselves.

At the time of the German attack, Denmark and Norway were neutral. Germany still attacked the countries because it feared that Great Britain and France planned to occupy Norway. With Denmark's access to the Baltic Sea in German hands, Swedish iron ore could be transported undisturbed to Germany. Sweden remained neutral.

The Battle of Britain

1940 - 1941 Great Britain

Shortly after the conquest of Western Europe, Germany attacked the United Kingdom. It had to do so by air because the British Navy was stronger than the German Navy. In July 1940, Germany started making air raids on ports and ships, airports, and places along the coast of England. Hitler had planned to invade England with an army, but this turned out to be impracticable because the German Air Force was unable to gain the upper hand. On 25 August 1940, the British Air Force bombed Berlin. This counter-attack did not cause much damage, but it did change the German plans.

Starting on 7 September, London was bombed for 57 consecutive days, and other English cities were hit hard as well. The German air raids continued into the autumn of 1941. They are collectively called "The Blitz", after the German word for lightning.